Contents

Summary

Congress has maintained significant interest in Mexico, an ally and top trade partner. In recent decades, U.S.-Mexican relations have been strengthened through cooperative management of the 2,000-mile border, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and security cooperation under the Merida Initiative. Relations have recently been tested, however, by President Donald J. Trump's shifts in U.S. immigration and trade policies.

President Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) is in the final year of his six-year term. During 2013, Peña Nieto shepherded significant structural reforms through the Mexican Congress, including a historic energy reform that opened Mexico's energy market to foreign investment. He has since struggled to implement some of those reforms, and to address human rights abuses and corruption. Homicides surpassed historic levels in 2017, hurting Peña Nieto's already relatively low approval ratings. The possibility of a U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA may have hindered investment, growth, and consumer confidence.

Political attention in Mexico is increasingly focused on presidential and legislative elections scheduled for July 1, 2018. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the leftist populist leader of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party, leads among presumptive candidates. Others include José Antonio Meade (former finance minister) for the PRI; Ricardo Anaya (former president of the conservative National Action Party, or PAN) for a coalition between the PAN and the leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD); and Margarita Zavala, wife of former President Felipe Calderón, as an independent. Some observers are concerned that a López Obrador victory could signal a significant change in Mexico's historically investor-friendly policies and cause friction with the United States, but others predict that he would govern pragmatically.

U.S. Policy

U.S.-Mexican relations remain relatively strong, but periodic tensions have emerged since January 2017. In recent years, both countries have prioritized bolstering economic ties, particularly energy cooperation; interdicting illegal migration from Central America; and combating drug trafficking, including heroin and fentanyl. Security cooperation has continued under the Merida Initiative, a security partnership for which Congress has provided Mexico some $2.7 billion since FY2008.

In January 2017, President Trump's assertion that Mexico should pay for a border wall that it has consistently opposed led Peña Nieto to cancel a White House visit. Although the Mexican government continues to oppose paying for the border wall and is concerned about the future of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) initiative, which has shielded some 550,000 Mexicans from deportation, bilateral security and migration management efforts continue. The Trump Administration requested $85 million for the Merida Initiative for FY2018 (a 35% decline from FY2017). Mexican leaders are preparing for a possible U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA, which could severely impact the Mexican economy, although renegotiations continue.

Legislative Action

The 115th Cong ress has considered legislation affecting Mexico. Congress provided $130.9 million in FY2017 for the Merida Initiative in P.L. 115-31. The House Appropriations Committee's FY2018 State Department and Foreign Operations appropriations bill, H.R. 3362 (H.Rept. 115-253), incorporated into H.R. 3354, recommends $129 million for the Merida Initiative. The Senate Appropriations Committee's version of the bill, S. 1780 (S.Rept. 115-152), recommends $139 million. The Senate passed a resolution (S.Res. 83) calling for U.S. support for Mexico's efforts to combat fentanyl. The House approved a bipartisan resolution reiterating the importance of bilateral cooperation (H.Res. 336).

Further Reading

CRS Report R41349, U.S.-Mexican Security Cooperation: The Mérida Initiative and Beyond.

CRS In Focus IF10400, Transnational Crime Issues: Heroin Production, Fentanyl Trafficking,

and U.S. -Mexico Security Cooperation.

CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Immigration Control Efforts.

CRS Report RL32934, U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications.

CRS Report R44981, NAFTA Renegotiation and Modernization.

CRS Report R44907, NAFTA and Motor Vehicle Trade.

CRS Report R44875, The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and U.S.

Agriculture.

CRS Report R44747, Cross-Border Energy Trade in North America: Present and Potential.

CRS Report R43312, U.S.-Mexican Water Sharing: Background and Recent Developments.

Introduction

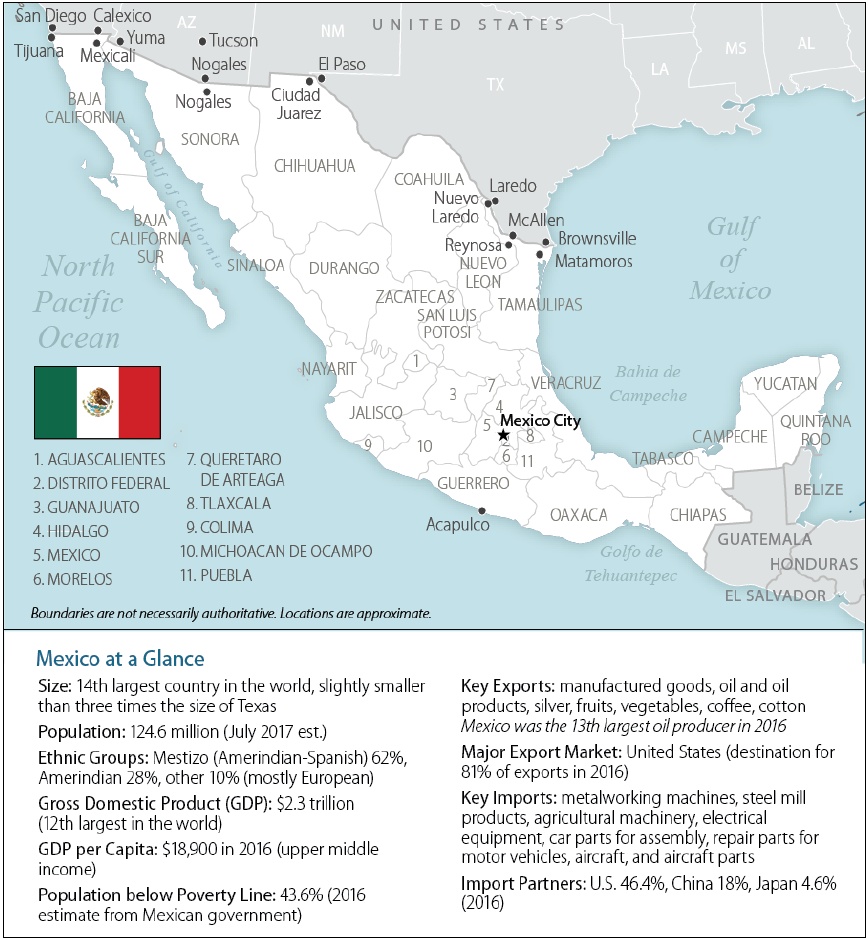

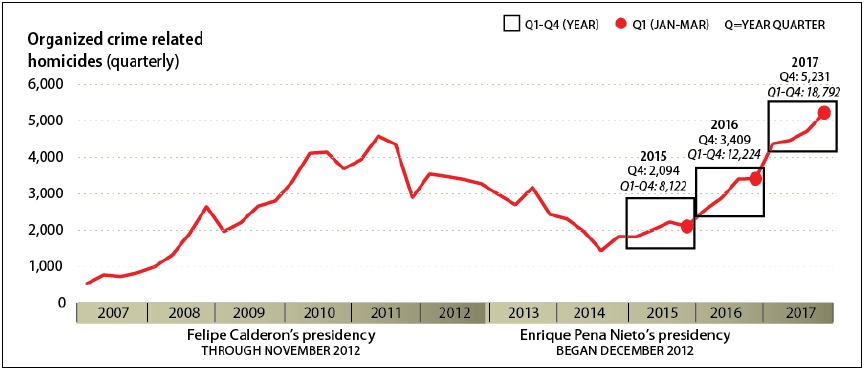

Over the past year, Congress has demonstrated renewed interest in Mexico, a top trade partner and energy supplier with which the United States shares a nearly 2,000-mile border and strong cultural, familial, and historical ties (see Figure 1). Economically, the United States and Mexico are very interdependent, and U.S. policymakers are closely following efforts to renegotiate the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that began in August 2017. |1| Similarly, security conditions in Mexico affect U.S. national security, particularly along the U.S.-Mexican border. |2| Observers are concerned about resurgent organized crime-related violence in Mexico, which reached record levels in 2017 (see Figure 2). |3|

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto is in the fifth year of his six-year term. In 2013, President Peña Nieto shepherded structural reforms through the Mexican Congress by forming an agreement among his Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the conservative National Action Party (PAN), and the leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) (see Table A-1 in Appendix). Some of those reforms have advanced, including historic energy reforms. However, others, including education reform, have stalled. Peña Nieto's approval rating has remained relatively low since 2014, as his government has struggled to solve high-profile human rights cases, become embroiled in corruption scandals, and faced security challenges. Economic growth has averaged 2% annually but has been hindered by uncertainty over the future of NAFTA.

The upcoming July 1, 2018, presidential and legislative elections could have a significant impact on Mexico's political and economic situation, as well as on its posture toward the United States. Thus far, discontent with the PRI and divisions within the PAN and the coalition it has formed with the PRD has led voters to favor leftist populist Andres Manuel López Obrador for president. Although some fear that López Obrador would reverse Mexico's reforms and damage U.S. relations, others predict that he would govern as a moderate, given his likely lack of a legislative majority and the difficult fiscal and security situation he would inherit (see "Elections: Recent and Upcoming").

This report provides an overview of political and economic conditions in Mexico, followed by assessments of selected issues of congressional interest in Mexico: security and foreign aid, extraditions, human rights, trade, migration, energy, education, environment, and water issues.

Political Situation

Over the past two decades, Mexico has transitioned from a centralized political system dominated by the PRI to a true multiparty democracy. Since the 1990s, presidential power has become more balanced with that of Mexico's Congress and Supreme Court. Partially as a result of these new constraints on executive power, the country's first two presidents from the PAN–Vicente Fox (2000-2006) and Felipe Calderon (2006-2012)–struggled to enact some of the reforms designed to address Mexico's economic and security challenges.

Figure 1. Mexico at a Glance

Sources: Graphic created by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). Map files from Map Resources. Trade data from Global Trade Atlas. Data are from CIA, The World Fact Book, updated December 12, 2017.

The Calderón government pursued an aggressive anticrime strategy and increased security cooperation with the United States. Mexico arrested and extradited many drug kingpins, but some 60,000 people died due to organized crime-related violence. Mexico's security challenges overshadowed some of the government's achievements, including its economic stewardship during the global financial crisis, health care expansion, and efforts on climate change.

Twelve years after losing the presidency for the first time in 71 years, the PRI candidate Enrique Peña Nieto won the 2012 presidential election over López Obrador of the leftist PRD. López Obrador subsequently left the PRD and founded his own National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party. In 2012, voters viewed the PRI as best equipped to reduce violence and hasten economic growth, despite concerns about its reputation for corruption. Enrique Peña Nieto took office with his party controlling 20 of 32 governorships, but his PRI/Green Ecological Party (PVEM) coalition lacked a legislative majority. The PRI/PVEM's control over the legislature further declined after midterm congressional elections held in 2015.

Structural Reforms: Enacted but Implemented Unevenly

In 2013, President Peña Nieto shepherded structural reforms through a fragmented legislature by forming a "Pact for Mexico" agreement among the PRI, PAN, and PRD. The reforms addressed a range of issues, including education, telecommunications, access to finance, and politics (see Table A-1 in Appendix). Constitutional reforms on energy opened Mexico's oil, natural gas, and power sectors to private investment for the first time in more than 70 years but led to the collapse of the pact in late 2014, due to the PRD's opposition to the energy reform. Through 2017, oil companies had committed to invest some $60 billion in Mexico's onshore and offshore blocks. |4|

Many analysts praised President Peña Nieto and his advisers for focusing their attention and political capital on shepherding structural reforms through the Mexican Congress but predicted that the reforms' impact would depend on how well they were implemented. Mexico's ranking in the World Economic Forum's Global Competiveness Index for 2017 improved, in part due to some of the reforms. (see "Factors Affecting Economic Growth"). Nevertheless, although some of Peña Nieto's reforms have begun to be implemented, many–particularly the education reform–have stalled. |5| More recently, critics have alleged that votes in favor of the reforms "were duly purchased" by the PRI and that the PRD and PAN are "perceived by the public, most likely correctly, as having sold their principles [and votes] to the PRI." |6|

Some of Mexico's reforms have faced problems due to issues in implementation; others have faced opposition from entrenched interest groups; and still others have been hindered by unfavorable global conditions. Fiscal reforms have been inhibited by challenges in tax collection, and a 2017 Supreme Court ruling reportedly watered down the telecommunications reform. |7| Teachers unions, particularly in Mexico's southern states, have vehemently opposed education reforms requiring teacher evaluations and accountability measures. In June 2016, 8 people died and more than 100 were injured after unions and police clashed in Oaxaca.

Security Setbacks

President Peña Nieto campaigned on a promise to reduce violence in Mexico. However, five years later, insecurity has risen sharply (see Figure 2). Organized crime-related homicides in Mexico rose slightly in 2015 and significantly in 2016. |8| In 2017, total homicides and organized crime-related homicides reached record levels. |9| The State Department has warned Americans not to travel to 5 of Mexico's 32 states and to reconsider whether to travel to another 11 states. |10| There are already concerns about election-related violence, particularly in Guerrero (where several politicians have already been killed). |11|

Infighting among criminal groups has intensified since the rise of the Jalisco New Generation, or CJNG, cartel, a group that shot down a police helicopter in September 2016. The January 2017 extradition of Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman has prompted succession battles within Sinaloa and emboldened the CJNG and other groups to challenge Sinaloa's dominance. Crime groups are competing to supply surging U.S. demand for heroin and other opioids. Mexico's criminal organizations also are fragmenting and diversifying away from drug trafficking, furthering their expansion into activities such as oil theft, alien smuggling, kidnapping, and human trafficking. Although much of the crime–particularly extortion–disproportionately affects localities and small businesses, fuel theft has become a national security threat, costing Mexico as much as $1 billion a year and fueling violent conflicts between the army and suspected thieves.

Figure 2. Estimated Organized Crime-Related Violence in Mexico

(2007-2017)

Source: Lantia Consultores, a Mexican security firm. Graphic prepared by CRS.

Early in his term, President Peña Nieto launched a national crime prevention plan, established a unified code of criminal procedures to cover the federal and state judiciaries, and increased funding for the country's transition to an accusatorial justice system. |12| In June 2016, Mexico transitioned from an inquisitorial, closed-door process based on written arguments presented to a judge to an adversarial system with oral arguments and the presumption of innocence. During the new system's first year in operation, 15% of indictments occurred as a result of a police investigation; the rest occurred when the perpetrator was caught in the act of committing a crime (such as possessing drugs). |13| Botched investigations have resulted in thousands of prisoners being released from prison by judges, leading many citizens to blame the new justice system for rising crime rates. |14|

Criticism of Peña Nieto's security strategy has mounted since 2014. Many observers assert that Peña Nieto has maintained Calderón's reactive approach of deploying federal forces–including the military–to areas in which crime surges rather than proactively strengthening institutions to deter crime and violence. |15| In December 2017, the government enacted an internal security law to provide legal authority for continued military deployments despite harsh criticism from domestic and international human rights groups, the U.N., and others. |16| The law may violate Mexico's constitution and is facing legal challenges. Peña Nieto has said that he will wait to implement the law until the Supreme Court considers its constitutionality. |17|

High-value targeting of top criminal leaders has continued; at least 107 of 122 high-value targets identified by the government had been detained or killed by security forces as of June 2017. |18| That figure includes "El Chapo" Guzmán, who was recaptured in January 2016 after escaping from prison in July 2015. High-value targeting has contributed to crime groups splintering and diversifying their illicit activities into kidnapping, alien smuggling, and oil theft. Even as many groups have developed into multifaceted illicit enterprises, government efforts to seize criminal assets have been modest ($36 million in 2016) and attempts to prosecute money laundering cases have had "significant shortcomings." |19|

Human Rights Abuses, Corruption, and Impunity

Human Rights

In addition, criminal groups, sometimes in collusion with public officials, as well as state actors (military, police, state prosecutors, and migration officials), have continued to commit incidents of serious human rights violations. The vast majority of those abuses have gone unpunished. |20| Incidents such as the forced abduction and killing of 43 students in Iguala, Guerrero, in September 2014 have galvanized protests against impunity in Mexico. On average, fewer than 20% of homicides have been successfully prosecuted, suggesting high levels of impunity. |21|

In 2017, 12 journalists died in Mexico; at least 6 were targeted for their work, making Mexico the world's most violent country for journalists outside a war zone. |22| Some 75% of journalists surveyed by Freedom House do not have faith in the mechanisms created to protect them. |23| That figure is likely even higher now that news outlets have reported that the Peña Nieto government has used spyware to monitor its critics, including journalists. The government acknowledged purchasing the spyware but denied using it for espionage. |24|

For years, human rights groups and annual U.S. State Department human rights reports have chronicled cases of Mexican security officials' involvement in extrajudicial killings, torture, and enforced disappearances. |25|

Tlatlaya, State of Mexico. In October 2014, Mexico's National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) issued a report concluding that at least 15 people had been killed by the Mexican military in Tlatlaya on July 1, 2014. The military originally claimed that the victims were criminals killed in a confrontation. The CNDH also documented claims of the torture of witnesses to the killings by state officials. The last three soldiers in custody for killing eight people on that day were released in May 2016. |26|

Iguala, Guerrero. The unresolved case of 43 missing students who disappeared in Iguala, Guerrero, in September 2014–which allegedly involved the local police and authorities–galvanized global protests. The government's investigation has been widely criticized, and aspects of it have been disproven by a group of experts from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). The government worked with those experts to reinvestigate the case in 2015-April 2016 but denied their requests to interview soldiers who were in the area of the incident. In July 2016, the government formed a follow-up mechanism with the IACHR to help ensure that the experts' lines of investigation were followed up on, but little progress has been made in resolving the case. |27| The Mexican government may also have used spyware against some of the IACHR experts. |28|

In response to criticism of the aforementioned human rights incidents, President Peña Nieto proposed 10 actions to improve the rule of law in late 2014. Proposals that have advanced include launching a national 911 emergency line, reforming the national anticorruption system, and enacting laws against torture (in April 2017) and enforced disappearances (in October 2017). |29| Additional policy changes, including police reforms, have been broadly debated but not enacted. Many say a botched police operation in November 2017 that resulted in the killing of four women and two children in Temixco, Mexico, illustrates the violent tactics that are still used. |30|

Corruption and Impunity

Although President Peña Nieto's proposals focused on confronting corruption at the municipal level, corruption is a major issue at the state and federal levels. President Peña Nieto and his wife, as well as former Finance Minister Videgaray, have been cleared of misconduct by a government auditor, but reports of how they benefitted from ties to a firm that has won many government contracts tarnished the government's image. The former PRI party treasurer has been arrested, and the chair of Peña Nieto's 2012 campaign (and former head of Pemex) is under investigation for receiving bribes from Odebrecht, a Brazilian construction firm. |31| Seventeen former governors have been convicted or are under investigation for fraud and other crimes. |32|

In July 2016, Mexico's Congress approved secondary legislation to fully implement the national anticorruption system that was created by a constitutional reform in April 2015. The legislation reflected several of the proposals that had been pushed by Mexican civil society groups. The reforms gave the anticorruption system investigative and prosecutorial powers and a civilian board of directors; increased administrative and criminal penalties for corruption; and required three declarations (taxes, assets, and conflicts of interest) from public officials and contractors. |33| Members of the anticorruption board maintain that the government has been "thwarting" its efforts by denying requests for information and failing to appoint an anticorruption prosecutor and judges to hear corruption cases. |34|

Mexico's Office of Attorney General generally has been incapable of resolving high-profile cases, including human rights abuses allegedly committed by security forces. |35| Since 2015, federal prosecutors have secured only one federal conviction for corruption. |36| Three attorneys general have resigned in five years. Civil society groups therefore have focused their efforts on urging President Peña Nieto and the Mexican Congress to create an independent national prosecutor's office to replace the Office of Attorney General, which is dependent on the President, and to name a respected independent person to lead the new institution. |37| The government has yet to do so, however, and it may be difficult for the various parties to agree on a candidate as the 2018 elections approach.

Foreign Policy

President Peña Nieto has prioritized promoting trade and investment in Mexico as a core goal of his Administration's foreign policy. During his term, Mexico has begun to participate in U.N. peacekeeping efforts and to speak out in the Organization of American States on the deterioration of democracy in Venezuela, a departure for a country with a history of nonintervention. Peña Nieto has sought to create closer trade ties with Europe, Asia, and the rest of Latin America; these efforts could become more important should Mexican-U.S. trade decline. He has hosted Chinese Premier Xi Jinping for a state visit to Mexico, visited China twice, and vowed to bolster ties.

The Peña Nieto government negotiated and signed the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement with other Asia-Pacific countries (and the United States and Canada). Even after President Trump withdrew the United States from the TPP agreement, Mexico has continued efforts with other signatories to conclude a similar agreement in 2018. Those former TPP countries signed an agreement on the core principles of that trade mechanism in November 2017. |38| Mexico has prioritized economic integration efforts with the pro-trade Pacific Alliance countries of Chile, Colombia, and Peru and focused on expanding markets for those governments. |39| Mexico is close to concluding a modernization of a free-trade agreement (FTA) with the European Union and may seek a FTA with the United Kingdom. Mexico currently has a total of 11 FTAs involving 46 countries. |40| Relations with Canada have improved since 2016, when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau removed a visa requirement for Mexicans visiting Canada and Mexico lifted a ban on Canadian beef imports.

Mexico is investing in Central American energy integration projects and supporting the "northern triangle" (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras) governments' "Alliance for Prosperity" proposal to promote development. The Mexican and U.S. governments cohosted a conference on growth and investment in security in Central America in June 2017.

Elections: Recent and Upcoming

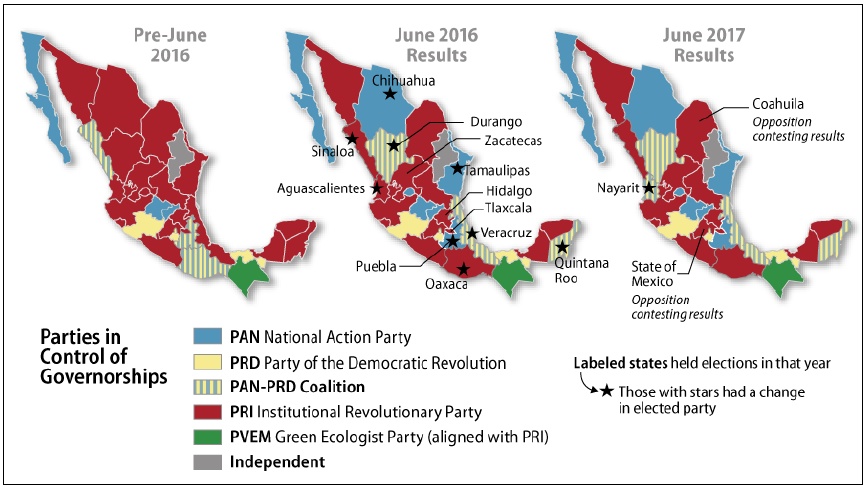

In June 2016, 12 of Mexico's 32 states held elections. Eight states saw the incumbent party lose; in four–Veracruz, Quintana Roo, Chihuahua, and Durango–the PRI lost for the first time in the party's history. The PAN emerged stronger from the gubernatorial elections, winning 11 governorships, either by itself or in a coalition with the PRD (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Gubernatorial Election Results: 2016 and 2017

Source: Mexico's National Electoral Institute.

The last major elections before the 2018 presidential contest took place on June 4, 2017. Those elections included gubernatorial contests in the state of Mexico (President Peña Nieto's home state), Nayarit, and Coahuila. The PRI won in Coahuila and in the state of Mexico. The PRI's relatively narrow margin of victory over the MORENA candidate (less than 3%) in the state of Mexico may not bode well for the party's prospects in the 2018 elections.

Mexico is scheduled to convene presidential and legislative elections on July 1, 2018. This election marks the first national contest presided over by the National Electoral Institute (INE), as opposed to a Federal Electoral Institute and separate state electoral entities. Observers have warned INE and the country's electoral courts to closely monitor the role of illicit financing in the campaigns, establish guidelines for the use of social media, work with security forces to prevent further election-related violence (which already has erupted), and prevent any hacking or other outside interference in the upcoming elections. |41| These elections are also the first contests to involve independent candidates and to allow those elected senator or deputy to run for reelection. The 2018 campaign is set to run from March 27 through June 27, 2018. Since there is no second round, analysts are predicting a very close election. The presumptive presidential candidates are as follows:

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (leftist Movement for National Regeneration, or MORENA; and Worker's Party, or PT; and conservative religious Social Encounter Party, or PES) is a former mayor of Mexico City who twice ran for president for the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD). López Obrador narrowly lost the presidential election in 2006 and protested the results. After finishing second in 2012, López Obrador split from the PRD to form MORENA. López Obrador has been described as a leftist populist and a nationalist, but he has moderated some of his positions, proposing combating corruption, adopting austerity, creating jobs and educational opportunities so that youth will not become involved in crime, boosting agricultural development, and revisiting the 2013 energy reforms to increase Mexican oil and gas production. His proposal to negotiate with crime groups has drawn criticism. |42| Many analysts maintain that he would take tougher stances than the current government has against any U.S. trade or migration policies that might be seen to be hostile. In mid- January 2018, López Obrador polled at 26.3% of voter preferences among the presumptive nominees. |43|

Ricardo Anaya Cortés ("For Mexico in Front," a coalition composed of the right and the left;the conservative National Action Party, or PAN; and the leftist PRD and Citizen's Movement, or MC party) is a former legislator and president of the PAN. During his tenure as party president, the PAN captured several governorships, many in coalitions with the PRD. Anaya outmaneuvered former First Lady Margarita Zavala (who is now running as an independent) to capture the PAN nomination. Anaya's trade and security policies are likely to be similar to those of the two previous governments and similar to those of José Antonio Meade Kuribreña. Ideological differences could make it difficult to hold Anaya's coalition together. His support stands at roughly 20.4%.

José Antonio Meade Kuribreña (centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI; Green Ecological Party, or PVEM; and National Alliance Party, or PANAL) is a former secretary of finance, foreign affairs, social development, and energy who has worked in PAN and, most recently, the PRI government of President Peña Nieto. He was an independent prior to 2017 and does not have strong historic ties to the PRI as Peña Nieto does. Meade is generally considered a technocrat who espouses market-friendly economic policies. He would likely continue close cooperation with the United States. Meade may be tainted by his association with the current PRI government, which has been riddled with corruption and human rights scandals, failed to address escalating violence, and seen inflation rise. Meade is facing questions about allegations of funds being misused at two of the ministries he directed. |44| He has recently polled at 18.2%.

Among the presumptive independent candidates are Margarita Zavala, a former legislator and first lady (2006-2012) and Jaime Rodríguez, the former governor of Nuevo León who became the country's first independent governor in 2015.

Economic and Social Conditions |45|

Over the last 25 years, Mexico has transitioned from a closed, state-led economy to an open market economy that, as mentioned, has entered into free trade agreements with 46 countries. The transition began in the late 1980s and accelerated after Mexico entered into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States and Canada in 1994. Since NAFTA, Mexico has increasingly become an export-oriented economy, with the value of exports equaling more than 38% of Mexico's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016, up from 10% of GDP 20 years ago. Mexico remains a U.S. crude oil supplier, but its top exports to the United States are automobiles and auto parts, computer equipment, and other manufactured goods. One report estimates that 40% of the content of those exports contain U.S. value added content. |46|

Despite attempts to diversify its economic ties and build its domestic economy, Mexico remains heavily dependent on the United States as an export market (roughly 80% of Mexico's exports in 2016 were U.S.-bound) and as a source of remittances, tourism revenues, and investment. Studies estimate that a U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA, which President Trump has repeatedly threatened, could cost Mexico more than 950,000 low-skilled jobs and lower its GDP growth by 0.9%. |47| In recent years, remittances have replaced oil exports as Mexico's largest source of foreign exchange. Remittances reached a record-high $27 billion in 2016 and likely exceeded that total in 2017. |48| In 2017, U.S. travel warnings about security conditions in Mexico contributed to a decline in U.S. tourism arrivals to Mexico. |49| A weakened peso has helped Mexico's overall tourism performance and some export industries, but the uncertainty that has contributed to the currency's decline in value against the dollar has weakened foreign direct investment. |50|

The Mexican economy grew by roughly 2.1% in 2017, but growth may slow to 1.9% in 2018. |51| In addition to concerns about the future of NAFTA, analysts warn that growth could decline if corporations choose to invest more in the United States than in Mexico due to the new U.S. corporate tax rate of 21% (Mexico's corporate rate is 30%). |52| Some observers believe that investor sentiment and the country's growth prospects also could worsen if Mexican voters elect Andres Manuel López Obrador and he decides to roll back investor-friendly reforms. |53|

Economic conditions in Mexico tend to follow economic patterns in the United States. When the U.S. economy is expanding, as it is now, the Mexican economy tends to grow. However, when the U.S. economy stagnates or contracts, the Mexican economy also tends to contract, often to a greater degree. Sound macroeconomic policies, a strong banking system, and recent structural reforms backed by a flexible line of credit with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have helped Mexico weather recent economic volatility. |54| Nevertheless, the IMF has recommended additional steps to deal with potential external shocks. These steps include improving tax collection, reducing informality, reforming public administration, and improving governance.

Factors Affecting Economic Growth

Over the past 30 years, Mexico has recorded a somewhat low average economic growth rate of 2.6%. Some factors–such as plentiful natural resources, a young labor force, and proximity to markets in the United States–have been counted on to help Mexico's economy grow faster in the future. Most economists maintain that those factors could be bolstered over the medium to long term by continued implementation of some of the reforms described in Table A-1.

At the same time, continued insecurity and corruption, a relatively weak regulatory framework, and challenges in its education system may hinder Mexico's future industrial competitiveness. Corruption costs Mexico as much as $53 billion a year (5% of GDP). |55| A lack of transparency in government spending and procurement, as well as confusing regulations and red tape, has likely discouraged some investment. Deficiencies in the education system, including a lack of access to vocational education, have led to firms having difficulty finding skilled labor. |56|

Mexico is extremely vulnerable to natural disasters, which impacts economic growth. In 2017, Mexico experienced two earthquakes that left hundreds dead and thousands without access to basic services. The first, which struck on September 7, 2017, registered a magnitude of 8.2, the strongest recorded in more than a century. It affected the southern Pacific coast, with most damage concentrated in Chiapas and Oaxaca. On September 19, 2017, a second earthquake struck central Mexico. The quake, which registered a magnitude of 7.1, collapsed some 40 buildings in Mexico City and killed close to 400 people. Repairing the damage from these earthquakes could exceed $2 billion. Although the earthquakes and several hurricanes hurt GDP growth in 2017, reconstruction could boost the economy in 2018.

Another factor affecting the economy is the price of oil. Because oil revenues make up a large, if lessening, part of the country's budget, low oil prices since 2014 have required budget cutbacks. The 2017 budget cut funding for all ministries, including the ministries of transport and education, which impact the businesses climate. |57| The government also has raised other taxes to recoup lost revenue from oil.

Many analysts predict that Mexico will have to combine efforts to implement its economic reforms with other actions to boost growth. A 2017 report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development suggests that Mexico will need to enact complementary reforms to address issues such as corruption, weak governance, and lack of judicial enforcement to achieve its full economic growth potential. |58|

Combating Poverty and Inequality

Mexico has long had relatively high poverty rates for its level of economic development (46% in 2014 and 43.6% in 2016), particularly in rural regions in southern Mexico and among indigenous populations. |59| Some assert that conditions in indigenous communities have not measurably improved since the Zapatistas launched an uprising for indigenous rights in 1994. |60| Traditionally, those employed in subsistence agriculture or small, informal businesses tend to be among the poorest citizens. Many households rely on remittances to pay for food, clothing, health care, and other basic necessities.

Mexico also experiences relatively high income inequality. According to the 2014 Global Wealth Report published by Credit Suisse, 64% of Mexico's wealth is concentrated in 10% of the population. Mexico is among the 25 most unequal countries in the world included in the Standardized World Income Inequality Database. According to a 2015 report by Oxfam Mexico, this inequality is due in part to the country's regressive tax system, oligopolies that have dominated particular industries, a low minimum wage, and a lack of targeting in some social programs. |61|

Economists have maintained that reducing informality is crucial for addressing income inequality and poverty, while also expanding Mexico's low tax base. The 2013-2014 reforms sought to boost formal-sector employment and productivity, particularly among the small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that employ some 60% of Mexican workers, mostly in the informal sector. Although productivity in Mexico's large companies (many of which produce internationally traded goods) increased by 5.8% per year between 1999 and 2009, productivity in small businesses fell by 6.5% per year over the same period. |62| To address that discrepancy, the financial reform aimed to increase access to credit for SMEs and the fiscal reform sought to incentivize SMEs' participation in the formal (tax-paying) economy by offering insurance, retirement savings accounts, and home loans to those that register with the national tax agency.

The Peña Nieto Administration has sought to complement economic reforms with social programs and, more recently, with the establishment of special economic zones (ZEEs) with low taxes and other investment incentives in the south of Mexico. |63| It expanded access to federal pensions, started a national anti-hunger program, and increased funding for the country's conditional cash transfer program. |64| Peña Nieto renamed that program Prospera (Prosperity) and redesigned it to encourage its beneficiaries to engage in productive projects. Despite recent budget austerity, funding for these programs has been largely protected, but some programs have been criticized for a lack of efficacy. |65|

U.S. Relations and Issues for Congress

Mexican-U.S. relations generally have grown closer over the past two decades. Common interests in encouraging trade flows and energy production, combating illicit flows (of people, weapons, drugs, and currency), and managing environmental resources have been cultivated over many years. A range of bilateral talks, mechanisms, and institutions have helped the Mexican and U.S. federal governments–as well as stakeholders in border states, the private sector, and nongovernmental organizations–find common ground on difficult issues, such as migration and water management. U.S. policy changes that run counter to Mexican interests in one of those areas could trigger responses from the Mexican government on other areas where the United States benefits from Mexico's cooperation, such as combating illicit drug production.

Over the past year, U.S.-Mexican relations have been tested by President Trump's rhetoric and shifts in U.S. immigration policies. Rhetoric regarding Mexican migrants during the 2016 U.S. campaign, executive orders to increase deportations and hasten the construction of a border wall, and President Trump's calls for Mexico to pay for the wall resulted in a canceled presidential meeting in January 2017. The two leaders met in July 2017 on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Germany, after which President Trump told reporters that he "absolutely" still wanted Mexico to pay for a wall. |66| In September 2017, the Trump Administration announced a phaseout of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) initiative, a program that has provided work authorization and relief from removal for more than 550,000 Mexican migrants brought to the United States as children who lack immigration status. |67| (See "Mexican-U.S. Immigration Issues.")

The Trump Administration has made NAFTA renegotiation a prominent initial priority of its trade policy. |68| President Trump has viewed the agreement as the "worst trade deal" and has stated that he may seek to withdraw from the agreement. He has focused on the trade deficit with Mexico as a major reason for his critique. Many economists, however, contend that the trade deficit is the product of U.S. macroeconomic policy and that FTAs are likely to affect the composition of trade but have little impact on the trade deficit. |69|

Tensions in bilateral relations have continued despite frequent meetings between Cabinet officials, including a December 2017 Cabinet-level meeting on security issues. |70| Uncertainty about U.S. policy toward Mexico has persisted, in part, because of contradictions between tough statements periodically expressed by President Trump and the more conciliatory statements occasionally made by some of his Cabinet officials. |71| Thus far in 2018, President Trump has made both statements in favor of continuing to negotiate NAFTA and threats to withdraw from the agreement. |72| His ultimate position on DACA is also as yet unclear.

Security, the Mérida Initiative, and U.S. Assistance |73|

State Department Assistance

U.S.-Mexican cooperation to improve security and the rule of law in Mexico has increased as a result of the development and implementation of the Mérida Initiative, a program developed by the George W. Bush and Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) governments. As proposed, the Mérida Initiative was to provide some $1.4 billion in counterdrug and anticrime assistance to Mexico and Central America, largely in the form of equipment and training for security forces, from FY2008 through FY2010. |74| U.S. appropriations for the Mérida Initiative since FY2008 (some $2.7 billion), constitute 2% of Mexico's total security budget of $10 billion per year but have enabled the U.S. government to help shape Mexico's security policy.

In 2011, the U.S. and Mexican governments agreed to broaden the scope of bilateral efforts to focus on four pillars: (1) disrupting organized criminal groups, (2) institutionalizing the rule of law, (3) creating a 21st-century border, and (4) building strong and resilient communities. From FY2012 to FY2017, funding for pillar two–building the rule of law–exceeded funds for all other pillars and military assistance no longer formed a part of the Mérida Initiative. Although some analysts praised the wide-ranging cooperation between the governments, others criticized the increasing number of priorities included in the Mérida Initiative.

Table 1. Estimated Merida Initiative Funding: FY2008-FY2018

($ in millions)

| Account | ESF | INCLE | FMF | Total |

| FY2008 | 20.0 | 263.5 | 116.5 | 400.0 |

| FY2009 | 15.0 | 406.0 | 39.0 | 460.0 |

| FY2010 | 9.0 | 365. | 265.2 | 639.2 |

| FY2011 | 18.0 | 117.0 | 8.0 | 143.0 |

| FY2012 | 33.3 | 248.5 | Not Applicable | 281.8 |

| FY2013 | 32.1 | 190.1 | Not Applicable | 222.2 |

| FY2014 | 35.0 | 143.1 | Not Applicable | 178.1 |

| FY2015 | 33.6 | 110.0 | Not Applicable | 143.6 |

| FY2016 | 39.0 | 100.0 | Not Applicable | 139.0 |

| FY2017 | 40.9ª | 90.0 | Not Applicable | 130.9 |

| Total | 275.9 | 2,033.2 | 428.7 | 2,737.8 |

| FY2018 (request) | 25.0b | 60.0 | Not Applicable | 85.0 |

| FY2018 (House) | 39.0 | 90.0 | Not Applicable | $129.0 |

| FY2018 (Senate) | 49.0 | 90.0 | Not Applicable | $139.0 |

Sources: U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) budget office, November 3, 2016; U.S. Department

of State, November 18, 2016; U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations,

FY2018.

Notes: ESF = Economic Support Fund; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; FMF =

Foreign Military Financing. FY2008-FY2010 included supplemental funding.

a. For FY20I7, Mérida programs administered by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) were

funded through the Development Assistance account rather than ESF.

b. In the FY20I8 budget request, the Trump Administration proposes a new aid account to merge the Economic

Support and Development Fund accounts. It is to be known as the Economic Support and Development Fund

account, or ESDF.

In response to President Trump's executive orders on combatting transnational criminal organizations, or TCOs, (E.O. 13773) and enhancing border security (E.O. 13767), as well as Cabinet-level dialogues, new Mérida Initiative programs have prioritized those two areas. New programs have been designed to enhance Mexico's ability to combat money laundering, interdict illicit drug shipments at sea, and improve search-and-seizure operations along the border.

On December 14, 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and other Cabinet officials met with Mexican counterparts to discuss how to combat drug production, distribution, and sales by Mexican TCOs. This was the third Cabinet-level meeting on security since President Trump took office. The Trump Administration requested $85 million for the Merida Initiative in FY2018 (a 35% decline from the estimated FY2017 level). According to budget documents, the funds requested would help Mexico address narcotics trafficking (particularly of opioids), migration and border security challenges, and impunity and corruption.

Although budget requests for the Mérida Initiative have been declining, there has been bipartisan support in Congress for sustaining relatively level funding for the initiative (see Table 1). Congress is considering the FY2018 budget request and overseeing previously appropriated funding. The House Appropriations Committee's FY2018 State Department and Foreign Operations appropriations bill, H.R. 3362 (H.Rept. 115-253), incorporated into the House-passed full-year FY2018 Omnibus Appropriations Measure, H.R. 3354, recommends $129 million for the Merida Initiative. The Senate Appropriations Committee's version of the bill, S. 1780 (S.Rept. 115-152), recommends $139 million.

Department of Defense Assistance

In contrast to Plan Colombia, DOD did not play a primary role in designing the Merida Initiative and is not providing assistance through Mérida accounts. However, DOD oversaw the procurement and delivery of equipment provided through the FMF account. Despite DOD's limited role in the Merida Initiative, bilateral military cooperation has been increasing. DOD assistance aims to support Mexico's efforts to improve security in high-crime areas, track and capture suspects, strengthen border security, and disrupt illicit flows.

A variety of funding streams support DOD training and equipment programs. Some DOD equipment programs are funded by annual State Department appropriations for FMF, which totaled $5.0 million in FY2017. The FY2018 budget request would eliminate the FMF account. International Military Education and Training (IMET) funds, which totaled $1.5 million in FY2017, support training programs for the Mexican military, including courses offered in the United States. Apart from State Department funding, DOD provides additional training, equipping, and other support to Mexico that complements the Mérida Initiative through its own accounts. Individuals and units receiving DOD support are vetted for potential human rights issues in compliance with the Leahy Law. DOD programs in Mexico are overseen by U.S. Northern Command, which is located at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado. DOD counternarcotics support to Mexico totaled approximately $59.0 million in FY2017.

Policymakers may want to receive periodic briefings on DOD efforts to guarantee that DOD programs are being adequately coordinated with Merida Initiative efforts, complying with U.S. vetting requirements, and not reinforcing the militarization of public security in Mexico.

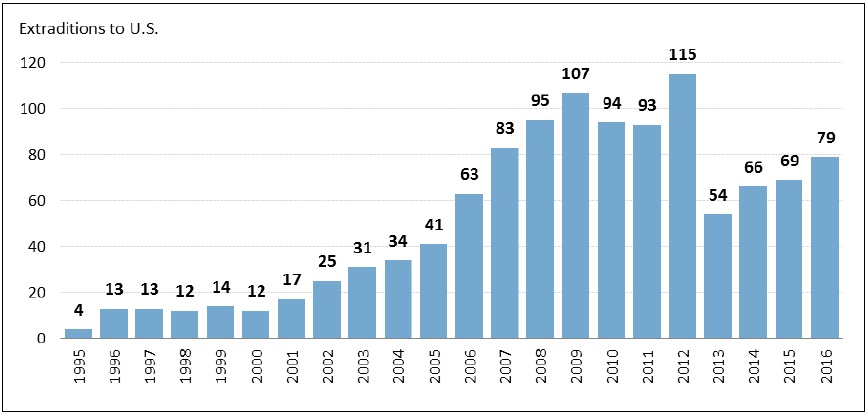

Extraditions

During the Calderon government, extraditions were another indicator that the State Department used as an example of the Merida Initiative's success. During the final years of the Calderon government, Mexico extradited an average of 98 people per year to the United States, an increase over the prior Administration. When President Peña Nieto took office, extraditions fell to 54 in 2013. They rose to 79 in 2016 (see Figure 4, below).

Figure 4. Extraditions from Mexico to the United States: 1995-2016

Sources: U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of State.

Some U.S. policymakers hope that "El Chapo" Guzman's July 2015 prison escape and subsequent extradition has definitively changed the Mexican government's position on extraditions. Congress may increase pressure on the Department of Justice and the State Department to push harder for extraditions in the future due to concerns about the security of Mexico's prisons and general corruption in its criminal justice system.

Human Rights |75|

The U.S. Congress has expressed ongoing concerns about human rights conditions in Mexico. Congress has continued to monitor adherence to the Leahy vetting requirements that must be met under the Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) of 1961, as amended (22 U.S.C. 2378d), which pertains to State Department aid, and 10 U.S.C. 2249e, which guides DOD funding. DOD reportedly suspended assistance to a brigade based in Tlatlaya, Mexico, due to concerns about the brigade's potential involvement in the extrajudicial killings previously described. |76| From FY2008 to FY2015, Congress made conditional 15% of U.S. assistance to the Mexican military and police until the State Department sent a report to appropriators verifying that Mexico was taking steps to comply with certain human rights standards. In FY2014, Mexico lost $5.5 million in funding due to human rights concerns. |77| For FY2016 and FY2017, human rights reporting requirements applied to FMF rather than to Mérida Initiative accounts. |78|

U.S. assistance to Mexico has increasingly focused on supporting the Mexican government's efforts to reform its judicial system and to improve human rights conditions in the country. Congress has provided funding to support Mexico's transition from an inquisitorial justice system to an oral, adversarial, and accusatory system that aims to strengthen human rights protections for victims and the accused. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is implementing $25 million in human rights programming that is part of the Merida Initiative and planned to run through 2018, including training for self-protection and digital security for journalists and a national campaign against torture.

In recent years, the Peña Nieto government has been faulted for not investigating and punishing serious human rights abuses committed by security forces and for not protecting journalists, migrants, and other vulnerable groups. Observers are particularly concerned about cases of torture, extrajudicial killings, and enforced disappearances, particularly since the Mexican Congress enacted a law in late 2017 to make the military's involvement in public security permanent. |79| Some urge the U.S. government to stop funding Mexico's military-led approach to public security. |80| Others recommend increasing U.S. support for judicial and police reform (particularly accountability and anticorruption programs) under pillar two of the Merida Initiative. |81| Many others recommend working with nongovernmental organizations to strengthen communities' abilities to exert oversight over the police and to report human rights abuses.

Congress may choose to augment Merida Initiative funding for human rights programs, such as ongoing training programs for military and police, or to fund new efforts to support human rights organizations. Human rights conditions in Mexico, as well as compliance with conditions included in the FY2017 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-31), are likely to be closely monitored. Some Members of Congress have written letters to U.S. and Mexican officials regarding human rights concerns, including allegations of extrajudicial killings by security forces, abuses of Central American migrants, and the use of spyware against human rights activists.

U.S. policymakers may question how the Peña Nieto Administration is moving to punish past human rights abusers, how it intends to prevent new abuses from occurring, and how the police and judicial reforms being implemented are bolstering human rights protections.

Economic and Trade Relations |82|

The United States and Mexico have a strong economic and trade relationship that has been bolstered over the past 20 years through NAFTA. Since 1994, NAFTA has removed virtually all tariff and nontariff trade and investment barriers among partner countries and provided a rules-based mechanism to govern North American trade. Most economic studies show that the net economic effect of NAFTA on the United States and Mexico has been relatively small but positive, though there have been adjustment costs to some sectors in both countries. Further complicating assessments of NAFTA's benefits, not all trade-related job gains and losses since NAFTA can be entirely attributed to the agreement. Numerous other factors have affected trade trends, such as Mexico's trade-liberalization efforts, economic conditions, and currency fluctuations.

Nevertheless, U.S.-Mexican trade has increased rapidly since NAFTA. The United States is Mexico's leading partner in merchandise trade, and Mexico is the United States' third-largest trade partner, after China and Canada. Mexico ranks second among U.S. export markets, after Canada, and is the third-leading supplier of U.S. imports. Total trade (exports plus imports) amounted to $525.2 billion in 2016. Much of the bilateral trade between the United States and Mexico occurs in the context of supply chains, as manufacturers in each country work together to create goods. The expansion of trade has resulted in the creation of vertical supply relationships, especially along the U.S.-Mexican border. The flow of intermediate inputs produced in the United States and exported to Mexico and the return flow of finished products increased the importance of the U.S.-Mexican border region as a production site.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is also an integral part of the bilateral economic relationship. The stock of U.S. FDI in Mexico increased from $17 billion in 1994 to $87.6 billion in 2016. |83| Mexican FDI in the United States is lower than U.S. investment in Mexico but also has increased in recent years. In 2016, Mexican FDI in the United States totaled $16.8 billion.

The Obama Administration engaged in bilateral efforts with Mexico to balance border security with facilitating legitimate trade and travel, promote economic competitiveness, and pursue energy integration. The U.S.-Mexican High-Level Economic Dialogue, launched on September 2013, was a bilateral initiative to advance economic and commercial priorities through annual Cabinet meetings. The High-Level Regulatory Cooperation Council launched in 2012 helped align regulatory principles. Trilateral (with Canada) cooperation occurred under the aegis of the North American Leadership Summits. While those mechanisms may or may not continue, the bilateral Executive Steering Committee (ESC), guiding broad efforts along the border, and the Bridges and Border Crossings group on infrastructure have continued to meet. |84|

Mexico, Canada, and the United States participated in negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, a proposed FTA with nine other Asia-Pacific countries that was signed on February 4, 2016. |85| On January 23, 2017, President Trump directed the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to withdraw the United States as a signatory to the TPP agreement; the acting USTR gave notification to that effect on January 30, 2017. |86| In November 2017, Mexico and 10 other former TPP countries agreed to the core elements of a new agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) to replace the TPP; it is to be signed in March 2018.

Despite positive advances on many aspects of bilateral and trilateral economic relations, trade disputes continue to arise. The United States and Mexico have had a number of trade disputes over the years, many of which have been resolved. They have involved: country-of-origin labeling, tomato imports from Mexico, dolphin-safe tuna labeling, and NAFTA trucking provisions. |87| In 2017, Mexico and the United States concluded a suspension agreement on a U.S. antidumping and countervailing duty investigation on Mexican sugar exports to the United States in which Mexico agreed to certain limitations on its access to the U.S. sugar market. |88| On January 24, 2018, President Trump announced new tariffs on imported solar panels and washing machines under the Trade Act of 1974 that would include products coming from Mexico, a move that Mexico is likely to dispute. |89|

The Trump Administration has made NAFTA renegotiation and modernization a prominent priority of its trade policy. President Trump has described the agreement as the "worst trade deal" and has stated that he may seek to withdraw from the agreement, including in early 2018. |90| He has focused on the trade deficit with Mexico as a major reason for his critique. On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks to renegotiate NAFTA, as required by the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA). Negotiations started August 16, 2017. Six rounds of talks have been held since August 2017, with prospects for reaching an agreement looking uncertain.

Migration and Border Issues

Mexican-U.S. Immigration Issues

Immigration policy has been a subject of congressional concern over many decades, with much of the debate focused on how to prevent unauthorized migration and address the large population of unauthorized migrants living in the United States. Mexico's status as both the largest source of migrants in the United States and a continental neighbor means that U.S. migration policies– including stepped-up border and interior enforcement–have primarily affected Mexicans. |91| Due to a number of factors, more Mexicans have been leaving the United States than arriving, |92| and apprehensions are at 40-year lows. |93| Nevertheless, protecting the rights of Mexicans living in the United States, including those who are unauthorized and those who are currently enrolled in the DACA program, remains a top concern of the Mexican government. |94|

Since the mid-2000s, successive Mexican governments have supported efforts to enact immigration reform in the United States, while being careful not to appear to be infringing upon U.S. authority to make and enforce immigration laws. Mexico has made efforts to combat transmigration by unauthorized migrants and worked with U.S. law enforcement to combat alien smuggling and human trafficking. |95| In FY2016, the Obama Administration removed (deported) some 149,821 Mexicans, down from a peak of 289,686 deportations in FY2013. |96| The volume of deportations versus voluntary returns was higher during the Obama Administration than during the Bush and Clinton Administrations, even as the overall number of people returned to Mexico was lower. |97| In recent years, some of Mexico's top concerns about U.S. removal policies, including nighttime deportations and issues with use of force by U.S. Border Patrol, have been addressed through bilateral migration talks and letters of agreement. |98|

Donald Trump made promises of restricting immigration, which he variously described as a threat to U.S. security and to economic prosperity, a central component of his campaign. |99| Within days of taking office, President Trump signed a series of executive orders on immigration. Of those, executive orders focused on hastening construction of a border wall (E.O. 13677) and increasing interior enforcement (E.O. 13678) likely have had the most direct impact on Mexico and Mexican citizens living unlawfully in the United States. |100| The Trump Administration's September 2017 announcement to phase out the DACA program beginning in March 2018 barring legislative action also would disproportionately impact Mexicans (three-quarters of all DACA recipients).

Congress has considered the amount and type of funding to provide for border infrastructure (e.g., what President Trump has described as a border wall). The Trump Administration asked for $1.4 billion in FY2017 supplemental appropriations for U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), including $1 billion "for planning, design, and construction of the first installment of the border wall." |101| Congress responded to the request in the FY2017 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-31), which provided a total of $533 million for border assets and infrastructure in annual and supplemental appropriations, including funding for repairs and upgrades to existing border barriers. |102| The Administration asked for some $1.6 billion for construction of the border wall in its FY2018 Department of Homeland Security budget request. The House-passed full-year FY2018 Omnibus Appropriations Measure, H.R. 3354, recommended meeting that request. It is as yet unclear how much border security funding will be in the final FY2018 appropriations bill.

In E.O. 13678, the Trump Administration broadened the categories of authorized immigrants that can be prioritized for removal. According to the Migration Policy Institute, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrested 42% more individuals (including Mexicans) from January 20, 2017, through the end of September 2017 and removed 37% more individuals from the interior of the United States than in the same period in 2016. Of those arrested, almost 30% reportedly had no criminal conviction. |103| As a result, the profile of Mexican deportees reportedly includes more individuals who have no criminal record and have spent many decades in the United States than in recent years (when the Obama Administration had focused on recent border crossers and those with criminal records). |104|

The potential for large-scale removal of Mexican nationals present in the United States without legal immigration status is a primary concern of the Mexican government that reportedly has repeatedly been expressed to Trump Administration officials. |105| Mexico's consular network in the United States has bolstered the services offered to Mexicans in the United States, including access to identity documents and legal counsel. It has launched a 24-hour hotline and mobile consultants to provide support, both practical and psychological, to those who may have experienced abuse or are facing removal. Mexico will not accept non-Mexican nationals who illegally entered the United States via the U.S.-Mexican land border (as DHS had reportedly proposed). |106| The Mexican government also has expressed opposition to another reported DHS proposal that would detain children and parents apprehended on the southwestern border in separate facilities to deter illegal crossings by families. |107|

The Mexican government has expressed hope that the U.S. Congress will develop a solution to resolve the phased ending of the DACA initiative and has said that it would welcome and provide support to any DACA enrollees that may be deported. |108| As of September 2017, some 550,000 Mexicans brought to the United States as children had received work authorizations and relief from removal through DACA. |109| Many DACA recipients born in Mexico have never visited the country, and some do not speak Spanish.

Dealing with Central American Migration, Including Unaccompanied Children |110|

In 2014, the United States and Mexico experienced a surge in the unauthorized migration of unaccompanied children and family units from Central America. In response, Mexico–with U.S. support–increased its immigration enforcement efforts through the implementation of a Southern Border Plan. In 2015, Mexico apprehended nearly 172,000 migrants from the "northern triangle" (El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala) of Central America. In 2016, Mexico apprehended another 153,000 migrants from northern triangle countries, including more unaccompanied minors from those countries than in 2015. Although Mexico's monthly apprehensions of Central American migrants declined in the first five months of 2017, they began to creep upward in May. Through November 2017, Mexico apprehended 76,100 immigrants from Central America. |111| Should Mexico relax its enforcement efforts, tens of thousands of additional migrants could arrive annually to the U.S. border.

Mexico's Southern Border Plan has involved the establishment of 12 naval bases on the country's rivers and three security cordons, which stretch more than 100 miles north of the Mexico-Guatemala and Mexico-Belize borders, as well as the use of drones. Because Mexico does not have a border patrol, its National Institute of Migration (INM) agents are operating under a new enforcement directive alongside federal and state police forces and the military. These unarmed agents have worked with security forces to increase immigration enforcement along known migrant routes, including northbound trains and at bus stations. INM has improved the infrastructure at existing border crossings and created more than 100 mobile highway checkpoints. Increased operations along known migrant routes have led migrants to seek out more clandestine, and often extremely dangerous, pathways north. Crimes against migrants, sometimes committed by corrupt public officials, have continued unabated. |112|

Many migrants' rights activists have maintained that few migrants have been informed by INM agents of the right to request asylum, as required by Mexican law. Asylum applications increased significantly from 2014 to 2016, yet Mexico's Commission for the Aid of Refugees (COMAR) has reportedly had insufficient asylum officers to conduct outreach to inform individuals of their right to seek protection or to process claims efficiently. In 2016, the Mexican government increased the number of requests for asylum and humanitarian visas it granted with support from the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). UNHCR estimated that Mexico could receive up to 20,000 asylum requests in 2017. |113|

The State Department has allocated more than $100 million in Merida Initiative funds to support Mexico's southern border efforts. The State Department has delivered more than $24 million of that assistance, mostly in the form of nonintrusive inspection equipment, canine teams, and training. Two projects that are national in scope but will impact the southern border also have begun. One project is designed to create an automated biometrics system (worth $75 million); another is designed to develop a secure communications network for Mexican agencies (worth $75 million). The Department of Defense (DOD) has held training events for Mexican marines posted on the southern border and supported workshops involving Mexican, Guatemalan, and Belizean military forces. DOD also has provided at least $22 million in equipment for constructing navy bases, boats, and other supplies. U.S. funding implemented by UNHCR has helped INM develop a training program for migration officials to interview vulnerable populations, support COMAR, and conduct humane repatriations.

Modernizing the U.S.-Mexican Border

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, there have been significant delays and unpredictable wait times at the U.S.-Mexican border. |114| Concerns about those delays have increased in recent years as the majority of U.S.-Mexican trade is passing through a port of entry along the southwestern border, often more than once, as manufacturing processes between the two countries have become deeply integrated. Due to bilateral efforts discussed below, reductions in wait times at some points of entry have been achieved, yet infrastructure and staffing issues remain on both the U.S. and Mexican sides of the border. |115|

On May 19, 2010, the United States and Mexico declared their intent to collaborate on enhancing the U.S.-Mexican border as part of pillar three of the Merida Initiative. |116| A Twenty-First Century Border Bilateral Executive Steering Committee (ESC) has met annually since then, most recently in November 2017, to develop binational action plans and oversee implementation of those plans. The plans are focused on setting goals within broad objectives: coordinating infrastructure development, expanding trusted traveler and shipment programs, establishing pilot projects for cargo preclearance, improving cross-border commerce and ties, and bolstering information sharing among law enforcement agencies. In 2015, the two governments opened the first railway bridge in 100 years at Brownsville-Matamoros and launched three cargo pre-inspection test locations where U.S. and Mexican customs officials are working together. |117| A Mexican law allowing U.S. customs personnel to be armed in Mexico has hastened these bilateral efforts.

As Congress carries out its oversight function on U.S.-Mexican migration and border issues, questions that may arise include the following: How well is Mexico fulfilling its pledges to increase security along its northern and southern borders and to enforce its immigration laws? What is Mexico doing to address Central American migration through its territory? What is the current level of bilateral cooperation on border security and immigration and border matters, and how might that cooperation be improved? How well are the U.S. and Mexican governments balancing security and trade concerns along the U.S.-Mexican border? To what extent would the construction of a new border wall affect trade and migration flows in the region?

Energy |118|

The future of oil and natural gas production in Mexico is important for Mexico's economic growth, as well as for the U.S. energy sector. Mexico's state oil company, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), has struggled to counter declining oil and gas production and been forced to postpone investments due to fiscal challenges that have been exacerbated by relatively low oil prices. Fuel theft from Pemex pipelines costs the company some $1 billion in lost revenue each year, and violent clashes have taken place in cases where federal security forces have battled fuel thieves. |119| Pemex generally has been operating at a loss since 2012, but it recorded a profit for the first two quarters of 2017 due to higher oil prices before output fell following a series of natural disasters and the company again operated at a loss. |120| Pemex is promoting joint ventures and farm-out agreements to boost its performance, as its average oil production is now below 2 million barrels per day. Those types of arrangements likely will be crucial for developing the largest onshore field discovered in 15 years, which the company identified in October 2017. |121|

Mexico has significantly increased natural gas imports from the United States due to its inability to meet rising domestic demand for gas. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, Mexico's demand could more than double by 2020, as long as cross-border pipelines continue to be built and energy trade is allowed to continue unimpeded. |122| Some experts are concerned, however, about potential U.S. tax or trade policy changes that could hinder energy trade. For example, a tax on Mexican exports could dampen U.S. demand for Mexican crude oil and, in turn, prompt retaliatory tariffs that could reduce Mexican demand for U.S. refined exports. |123|

Mexico's 2013-2014 energy reforms were designed to transform Pemex into a "productive state enterprise" with more autonomy and lower taxes that is subject to competition with private investors. The reforms created different types of contracts for private companies interested in investing in Mexico, allowed companies to book reserves for accounting purposes, established a sovereign wealth fund, and created new regulatory agencies. Many analysts maintain that the reforms were generally well designed but that the way they are implemented–and the price of oil–will determine their impact. Should oil prices remain at current levels, shale resources and other unconventional fields may not be feasible to develop.

In July 2015, Mexico's Energy Ministry announced the bidding results for the first round of public bidding for shallow-water offshore exploratory blocks. The results were deemed disappointing by many energy analysts: only 2 of the 14 available blocks were awarded. The government then altered the terms offered to attract more interest. Subsequent bidding rounds held in 2015 proved more successful, and, in December 2016, Mexico auctioned off 44 blocks of deepwater resources. Mexico then auctioned off 10 of 15 shallow-water blocks available in a June 2017 offering, with much higher participation than in its 2015 shallow-water lease auction. |124| It has another large deepwater bid scheduled for January 31, 2018.

The reforms also opened Mexico's electricity sector to private generators. U.S. companies are increasingly moving into Mexico's electricity market; some participated in Mexico's first electricity auction, held in March 2016. |125| If power-sector reforms reduce Mexico's electricity costs, then Mexico's manufacturing sector, which is highly integrated with U.S. industry, likely will become more competitive.

In terms of energy trade, enactment of P.L. 114-113 allows U.S. crude oil to be marketed and sold to international buyers by repealing Section 103 of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 (EPCA; P.L. 94-163). By removing crude oil export restrictions, U.S. oil exports to Mexico can occur more efficiently. Shippers and buyers will not need to arrange an oil-for-oil exchange, nor will they have to apply with the U.S. Department of Commerce for approval.

Opportunities may exist for greater U.S.-Mexican energy cooperation in the hydrocarbons sector. The first leases already have been awarded in the Gulf of Mexico under the U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Agreement, which was approved by Congress in December 2013 (P.L. 113-67). Bilateral efforts to ensure that hydrocarbon resources are developed without unduly damaging the environment could expand, possibly through collaboration between Mexican entities and U.S. regulatory entities. Educational exchanges and training opportunities for Mexicans working in the petroleum sector could expand. The United States and Mexico could build upon efforts to provide natural gas resources to help reduce energy costs in Central America and connect Mexico to the Central American electricity grid, as discussed at a June 2017 conference on Central America cohosted by both governments. |126| Analysts also have urged the United States to offer more technical assistance to Mexico–particularly in deepwater and shale exploration–and to ensure that new cross-border pipelines are approved expeditiously.

Some observers contend that there is much at stake for the North American oil and gas industry in the NAFTA renegotiations, especially in regard to Mexico as an energy market for the United States. |127| In its NAFTA negotiating objectives, the United States expressed support for North American energy security and independence and promoted the continuation of energy market-opening reforms. |128| Notably, Mexico has specifically called for a modernization of NAFTA's energy chapter, in particular the reservations whereby Mexican oil and gas were excluded.

Although Mexico was traditionally a net exporter of hydrocarbons to the United States, the United States had a trade surplus in 2016 of almost $10 billion in energy trade as a result of declining Mexican oil production, lower oil prices, and rising U.S. natural gas and refined oil exports to Mexico. |129| Some observers contend that NAFTA's existing dispute settlement mechanisms in Chapters 11 and 20 will defend the interests of the U.S. government and U.S. companies doing business in Mexico. They argue that the dispute settlement provisions and the investment chapter of the agreement will help protect U.S. multibillion-dollar investments in Mexico. This is significant because the July 2018 elections in Mexico could bring to power a president who may not be a supporter of the reforms. |130|

In addition to monitoring energy-related issues as they pertain to NAFTA, oversight questions may focus on how the Transboundary Hydrocarbons Agreement is being implemented; the extent to which Mexico is developing independent and capable energy-sector regulators, particularly for deepwater drilling; and the fairness of the terms Mexico offers to private companies interested in investing in its hydrocarbons industry. Policymakers also are likely to follow the effects of security conditions in Mexico, on the one hand, and global energy prices, on the other, both of which affect the attractiveness of Mexico's energy sector.

Water and Floodplain Issues |131|

Various U.S.-Mexican boundary and water treaties and conventions designate the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) responsible for facilitating the resolution of issues arising during the application of these agreements. |132| IBWC and Congress may confront concerns on a few issues related to these binational treaties, including water management in the Rio Grande basin, the future of certain measures for binational cooperation in the Colorado River basin, and binational floodplain concerns related to proposals for border security structures.

Rio Grande Water Management

A 1944 water treaty establishes water allocations for the United States and Mexico from certain shared rivers. |133| In the lower Rio Grande basin, it is largely Mexico that is obligated to deliver water to the United States. |134| Mexico's compliance with treaty delivery requirements often has been accomplished through wet-weather flows (i.e., excess flows) during the five-year cycle rather than through purposeful releases from Mexican reservoirs to provide reliable delivery to the United States. In recent years, some congressional and Texas interests have raised concerns about the economic impacts of low or unpredictable water deliveries on Texas border counties. P.L. 114-113 required a report within 45 days of the bill's enactment "detailing efforts taken to establish mechanisms to improve transparency of data on, and predictability of, the water deliveries from Mexico to the United States to meet annual water apportionments to the Rio Grande, and actions taken to minimize or eliminate the water deficits owed to the United States." That report was submitted in February 2016. The Senate Appropriations Committee requested similar reporting in FY2017. |135|

In the future, as the result of anticipated onshore oil and gas development in northeastern Mexico, the use of basin water for hydraulic fracturing and the disposal of wastewaters may draw attention to binational water quality protections and monitoring.

For waters of the Rio Grande near El Paso, water sharing is determined largely by a 1906 convention. |136| Texas and New Mexico stakeholders have been interested in how water is delivered to Mexico when this portion of the Rio Grande basin is affected by drought.

Colorado River Cooperative Management