| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

Sep17

Reconstructing the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces:

Lessons from the U.S. Experience in Afghanistan

Back to topTABLE OF CONTENTS

Reconstructing the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces: Lessons From the U.S. Experience in Afghanistan is the second in a series of lessons learned reports to be issued by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. The report examines how the U.S. government–primarily the Departments of Defense, State, and Justice–developed and executed security sector assistance (SSA) programs to build, train, advise, and equip the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF), both unilaterally and as part of a coalition, from 2002 through 2016. The report identifies lessons to inform U.S. policies and actions at the onset of and throughout a contingency operation and provides recommendations for improved performance. In Afghanistan today, the U.S. effort to train, advise, and assist the ANDSF does not appear to be over. In light of the administration's current focus on strategy in Afghanistan, this report provides timely and actionable recommendations for our current and future efforts there.

Our analysis revealed that the U.S. government was not properly prepared from the outset to help build an Afghan army and police force that was capable of protecting Afghanistan from internal and external threats and preventing the country from becoming a terrorist safe haven. We found the U.S. government lacked a comprehensive approach to SSA and a coordinating body to successfully implement the whole-of-government programs necessary to develop a capable and self-sustaining ANDSF. Ultimately, the United States designed a force that was not able to provide nationwide security, especially as that force faced a larger threat than anticipated after the drawdown of coalition military forces.

SIGAR began its lessons learned program in late 2014 at the urging of General John Allen, Ambassador Ryan Crocker, and others who had served in Afghanistan. This report and those that follow comply with SIGAR's legislative mandate to provide independent and objective leadership and recommendations to promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness; prevent and detect fraud, waste, and abuse; and inform Congress and the Secretaries of State and Defense about reconstruction-related problems and the need for corrective action.

Unlike other inspectors general, SIGAR was created by Congress as an independent agency, not housed inside any single department. While other inspectors general have jurisdiction over the programs and operations of their respective departments or agencies, SIGAR has jurisdiction over all programs and operations supported with U.S. reconstruction dollars, regardless of the agency involved. SIGAR is the only inspector general focused solely on the Afghanistan mission, and the only one devoted exclusively to reconstruction issues. Because SIGAR has the authority to look across the entire reconstruction effort, it is uniquely positioned to identify and address whole-of-government lessons.

As Reconstructing the ANDSF has done, future lessons learned reports will synthesize not only the body of work and expertise of SIGAR, but also that of other oversight agencies, government entities, current and former officials with on-the-ground experience, academic institutions, and independent scholars. The reports will document what the United States sought to accomplish, assess what it achieved, and evaluate the degree to which these efforts helped the United States reach its strategic goals in Afghanistan. They will also provide recommendations to address the challenges stakeholders face in ensuring efficient, effective, and sustainable reconstruction efforts, not just in Afghanistan, but in future contingency operations. Other lessons learned reports, currently in progress, will cover a range of topics, including, but not limited to, counternarcotics, stabilization, and private sector development.

SIGAR's lessons learned program comprises subject matter experts with considerable experience working and living in Afghanistan, aided by a team of experienced research analysts. In producing its reports, the program also uses the significant skills and experience found in SIGAR's Audits, Investigations, and Research and Analysis directorates, and the Office of Special Projects. I want to express my deepest appreciation to the research team members who produced this report, and thank them for their dedication and commitment to the project.

I also want to thank all of the individuals–especially the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Joseph Dunford; Resolute Support mission commander, General John Nicholson; former Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan (CSTC-A) commander, Major General Richard Kaiser; deployed personnel at Resolute Support, the regional train, advise and assist commands, and the U.S. Embassy; senior agency officials at the Departments of Defense, State, and Justice; and academicians, subject matter experts, and others– who provided their time and effort to contribute to this report. It is truly a collaborative effort meant to not only identify problems, but also to learn from them and apply reasonable solutions to improve future reconstruction efforts.

I believe the lessons learned reports will be a key legacy of SIGAR. Through these reports, we hope to reach a diverse audience in the military services and the legislative and executive branches, at the strategic and programmatic levels, both in Washington and in the field. By leveraging our unique interagency mandate, we intend to do everything we can to make sure the lessons from the United States' largest reconstruction effort are identified, acknowledged, and, most importantly, remembered and applied to reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan, as well as to future conflicts and reconstruction efforts elsewhere in the world.

John F. Sopko

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction

Arlington, Virginia

September 2017

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

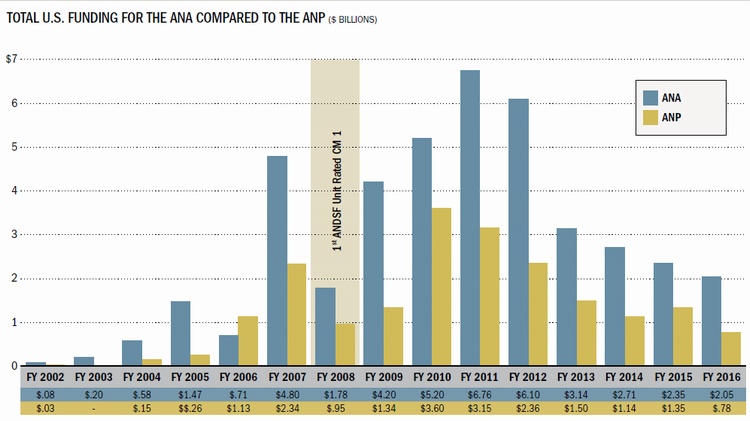

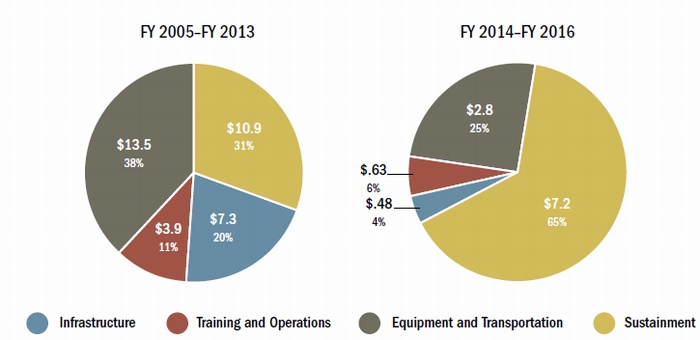

The development of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) is a cornerstone of the overall U.S. policy in Afghanistan and a key requirement of the U.S. strategy to transition security responsibilities to the Afghan government. Since 2002, the ANDSF has been raised, trained, equipped, and deployed to secure Afghanistan from internal and external threats, as well as to prevent the reestablishment of terrorist safe havens. To achieve this, the United States devoted over $70 billion (60 percent) of its Afghanistan reconstruction funds to building the ANDSF through 2016, and continues to commit over $4 billion per year to that effort.

This lessons learned report draws important lessons from the U.S. experience building the ANDSF since 2002. These lessons are relevant to ongoing efforts in Afghanistan, where the United States will likely remain engaged in security sector assistance (SSA) efforts to support the ANDSF through at least 2020. In addition, the United States currently participates in efforts to build other developing-world security forces as a key tenet of its national security strategy, an effort which we anticipate will continue and benefit from the lessons learned in Afghanistan. Finally, the report provides timely and actionable recommendations intended to improve our actions in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

This report examines the U.S. efforts to design, train, advise, assist, and equip the ANDSF and describes how these efforts waxed and waned within the policy priorities of the United States and other key donors. It charts the evolution of the mission from the initial U.S. agreement to serve as the lead nation for the development of the Afghan National Army (ANA), to later assuming a level of ownership for the success of the Afghan military and police forces, to ultimately making their development a critical precondition for reducing U.S. and coalition support over time. The report also describes how the U.S. government was ill-prepared to develop a national security force in a post-conflict nation; the changing resource requirements for ANDSF personnel, equipment, and funding; and the inherent tensions within and between the U.S. government and international coalition.

In addition, the report provides a detailed analysis of cross-cutting issues affecting ANDSF development. These issues include corruption, illiteracy, the role of women, the provision of weapons and equipment, high levels of ANDSF attrition, and the annual rotation of U.S. advisors and trainers.

Our report identifies 12 key findings regarding the U.S. experience developing the ANDSF:

1. The U.S. government was ill-prepared to conduct SSA programs of the size and scope required in Afghanistan. The lack of commonly understood interagency terms, concepts, and models for SSA undermined communication and coordination, damaged trust, intensified frictions, and contributed to initial gross under-resourcing of the U.S. effort to develop the ANDSF.

2. Initial U.S. plans for Afghanistan focused solely on U.S. military operations and did not include the development of an Afghan army, police, or supporting ministerial-level institutions.

3. Early U.S. partnerships with independent militias–intended to advance U.S. counterterrorism objectives–ultimately undermined the creation and role of the ANA and Afghan National Police (ANP).

4. Critical ANDSF capabilities, including aviation, intelligence, force management, and special forces, were not included in early U.S., Afghan, and NATO force-design plans.

5. The United States failed to optimize coalition nations' capabilities to support SSA missions in the context of international political realities. The wide use of national caveats, rationale for joining the coalition, resource constraints and military capabilities, and NATO's force generation processes led to an increasingly complex implementation of SSA programs. This resulted in a lack of an agreed-upon framework for conducting SSA activities.

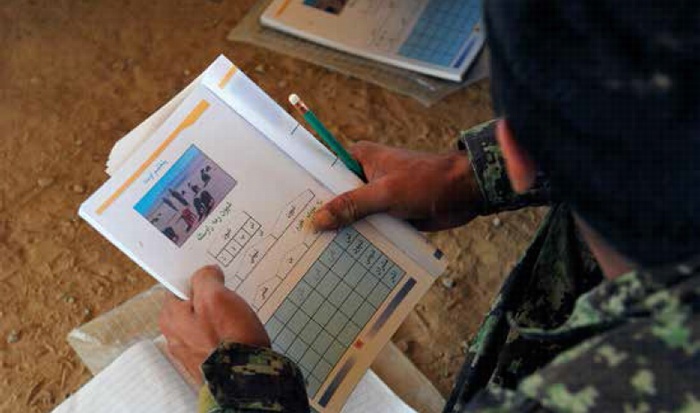

6. Providing advanced Western weapons and management systems to a largely illiterate and uneducated force without appropriate training and institutional infrastructure created long-term dependencies, required increased U.S. fiscal support, and extended sustainability timelines.

7. The lag in Afghan ministerial and security sector governing capacity hindered planning, oversight, and the long-term sustainability of the ANDSF.

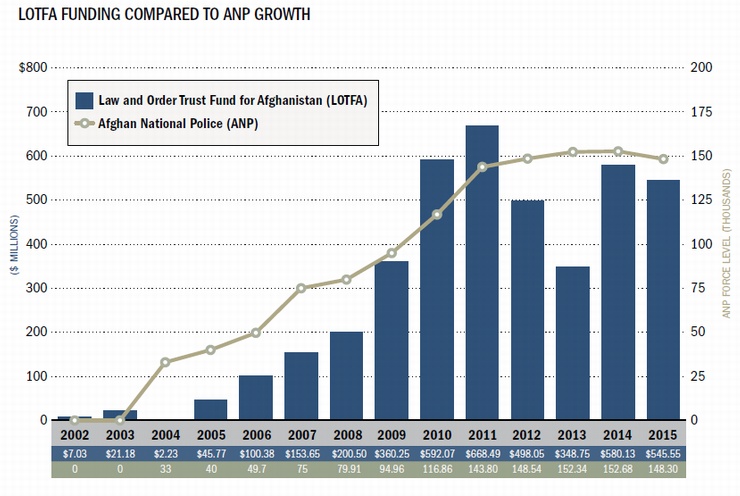

8. Police development was treated as a secondary mission for the U.S. government, despite the critical role the ANP played in implementing rule of law and providing local-level security nationwide.

9. The constant turnover of U.S. and NATO trainers impaired the training mission's institutional memory and hindered the relationship building required in SSA missions.

10. ANDSF monitoring and evaluation tools relied heavily on tangible outputs, such as staffing, equipping, and training levels, as well as subjective evaluations of leadership. This focus masked intangible factors, such as corruption and will to fight, which deeply affected security outcomes and failed to adequately factor in classified U.S. intelligence assessments.

11. Because U.S. military plans for ANDSF readiness were created in an environment of politically constrained timelines–and because these plans consistently underestimated the resilience of the Afghan insurgency and overestimated ANDSF capabilities–the ANDSF was ill-prepared to deal with deteriorating security after the drawdown of U.S. combat forces.

12. As security deteriorated, efforts to sustain and professionalize the ANDSF became secondary to meeting immediate combat needs.

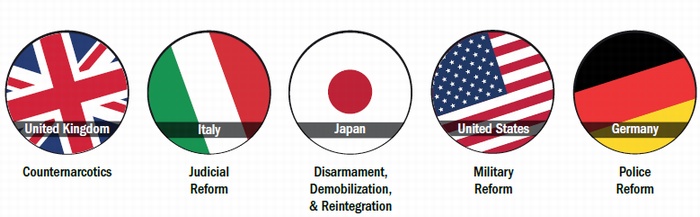

In 2002, the United States and its coalition partners concluded that the development of an internationally trained and professional Afghan national security force could serve as a viable alternative to an expansion of international forces in Afghanistan. Despite being ill-prepared and lacking proper doctrine, policies, and resources, the United States took the lead for building the ANA. Coalition partners accepted responsibility for other efforts: police reform (Germany), counternarcotics (United Kingdom), judicial reform (Italy), and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (Japan). General Karl Eikenberry, the first Security Sector Coordinator in Afghanistan, remarked that "overall, it might be termed exploratory learning because the many uncertainties of the Afghanistan mission added to the steepness of the learning curve." |1|

By May 2002, U.S. training of the new ANA began with the deployment of U.S. Special Forces to lead the effort. Recognizing that training a national army was beyond the core competency of the Special Forces, the United States deployed the 10th Mountain Division of the U.S. Army to expand the training program from small infantry units to larger military formations and develop defense institutions, such as logistics networks. In order to ensure sufficient U.S. combat support for the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Army National Guard assumed responsibility for the ANA training mission.

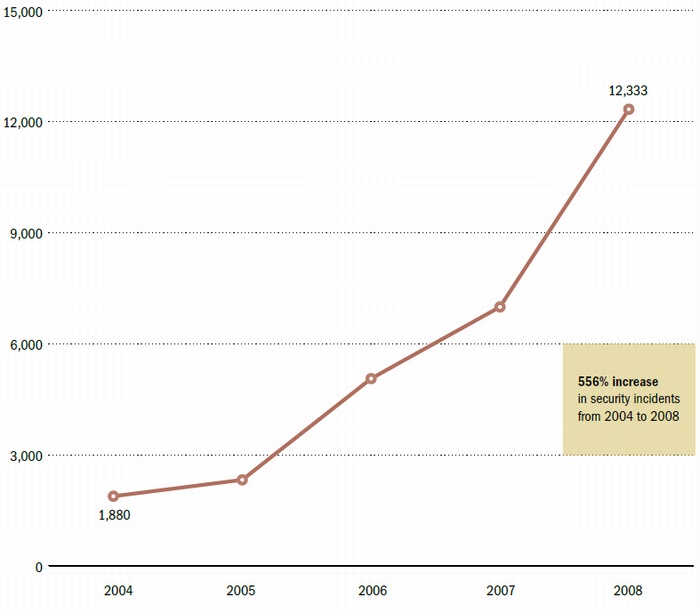

In 2004, the United Nations described Afghanistan as "volatile, having seriously deteriorated in certain parts of the country." |2| The director of the Defense Intelligence Agency reported that enemy attacks had reached "their highest levels since the collapse of the Taliban government." |3| The United States recognized that dividing security sector responsibilities among the coalition was not producing the desired results, requiring the Bush Administration to increase U.S. commitments. In 2005, the United States assumed the lead for developing both the ANA and the ANP, and in 2006, created the Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan (CSTC-A) as the proponent responsible for training, advising, assisting, and equipping the Afghan security forces.

When assuming the lead for the ANP mission, the United States failed to sufficiently coordinate police training programs and mission requirements with Germany, which had previously had the lead, and the European Union. The United States preferred a plan to militarize the police as a localized defense force, while the Europeans wanted a traditional community policing model. This led to conflicting training, advising, and assisting efforts and resulted in the current ANP identity crisis.

As U.S. and coalition military forces tried to get ahead of growing insecurity, the United States turned to rapidly expanding the ANDSF on a condensed training and development timeline. For the ANA, training capacity at the Kabul Military Training Center increased from two to five kandaks (U.S. Army battalion equivalents), and basic training was reduced from 14 weeks in 2005 to 10 weeks in 2007. In 2005, the U.S. military reported that of the 34,000 "trained" Afghan police officers, only 3,900 had been through the basic eight-week course, while the remainder had attended a two-week transition course. In contrast, police recruits in the United States–who are pulled from a highly literate pool of high school graduates–attend an average of 21 weeks of basic training, followed by weeks of field training.

The lack of appropriate equipment for the Afghan security forces threatened their combat readiness. According to a 2005 U.S. military report, some ANP units had less than 15 percent of the required weapons and communications systems on hand. |4| In 2006, retired General Barry McCaffrey concluded that the ANA was "miserably under-resourced" and such circumstances were becoming a "major morale factor for the force." |5|

Despite known issues with equipping the force, the United States pushed for the expansion of ANDSF force strength. By the end of 2006, senior U.S. officials told the Afghan government that the United States would withhold funding if the Afghans did not agree to expand the ANP from 60,000 to 82,000 police. And in 2008, the U.S. and Afghan governments agreed to expand the ANA from 75,000 to 134,000 (to include a new Afghan Air Force), without considering the associated fiscal and resource requirements.

As part of the expansion of the Afghan military, the United States initiated training of specialized units, transitioning the ANA from a light-infantry army to a combined arms service with army, air force, and special forces elements. The train, advise, and assist programs for these specialized forces were the most successful of the training efforts, and were based on the comprehensive and persistent approach taken by U.S. Special Operations Command and some elements of the U.S. Air Force. U.S. Special Forces implemented a rigorous 16-week training program–modeled on the U.S. Army Ranger program–that included close and enduring post-training mentorship in the field. This resulted in Afghan Special Forces becoming the "best-of-the-best" in the Afghan military. And, while still a fledgling institution (largely because the program was not initiated until 2006), the Afghan Air Force shows great promise; it recently increased its ability to provide close air support and lift to ground forces.

The U.S. government initiated three specialized police programs after 2005: the Afghan National Auxiliary Police, the Afghan Public Protection Program, and the Afghan Local Police. With limited oversight from and accountability to the Afghan government and the United States, these police forces were reported to have engaged in human rights abuses, drug trafficking, and other corrupt activities, ultimately serving as a net detractor from security. While the United States stopped supporting two of the programs due to these issues, the Afghan Local Police continue to operate today.

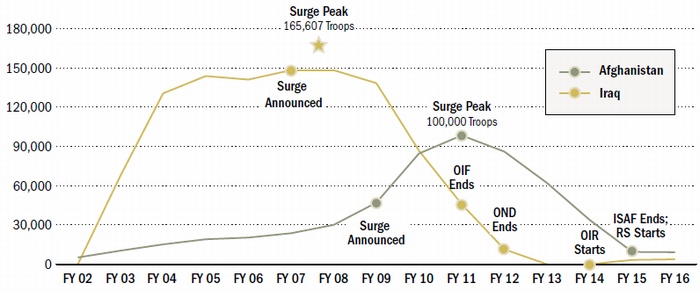

In 2009, with the Taliban threat increasing and the ANDSF struggling to secure the country, President Barack Obama authorized a surge of U.S. combat forces and agreed to increase ANDSF end-strength to 352,000. President Obama also announced a withdrawal date for combat forces and the transfer of security to the ANDSF beginning in mid-2011. With guidance from the president, the U.S. military pursued a strategy of rapidly improving security, while also supporting the development of a struggling ANDSF. This dual-track strategy resulted in an environment ripe for capacity substitution, where U.S. trainers and advisors augmented critical gaps in Afghan capability, providing enablers such as close air support, airlift, medical evacuation, logistics, and leadership to ensure success on the battlefield. At the same time, the mandate to conduct partnered operations with the ANDSF taught the Afghans to model their fighting on that of the United States, resulting in Afghan ground forces' increasing dependence on U.S.-provided advanced military capabilities.

Assessment tools used throughout the reconstruction effort evaluated tangible information, such as recruitment, training, and equipment, and failed to assess subjective factors, such as corruption, leadership, and battlefield performance. These assessment systems created disincentives for Afghan units to improve because the coalition prioritized supporting units with lower ratings. Furthermore, from 2005 to 2016, the United States used four different ANDSF assessment methodologies that resulted in inconsistent and often contradictory conclusions about the quality and readiness of the forces.

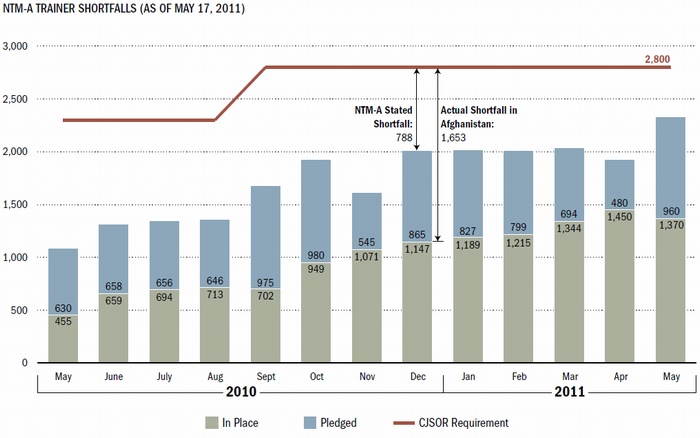

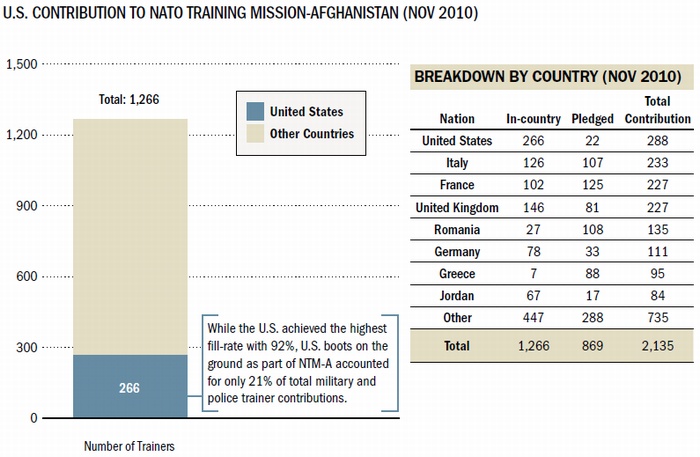

The ANDSF train, advise, and assist effort was chronically understaffed. In 2009, NATO established the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan (NTM-A) as a partner organization to CSTC-A. In February 2010, when NTM-A/CSTC-A became fully operational, only 1,810 of the required 4,083 trainers were in place. Similar shortages remained as time went on. Even in those areas deemed critical priorities, NTM-A struggled to meet its personnel requirements. In November 2010, for example, about 36 percent of instructor positions seen as critical priorities were unfilled. At a time when the ANA was rapidly expanding toward a force strength goal of 171,600, these staffing shortfalls at training facilities and in the field negatively affected planned ANDSF development. General John Craddock, Supreme Allied Commander Europe from 2006 to 2009, stated that "NATO nations have never completely filled the agreed requirements for forces needed in Afghanistan" since mission inception. |6|

With a poor monitoring and evaluation system, and the United States and NATO substituting for the capacity and capability of the ANDSF, it was not a surprise that, as U.S. and NATO forces drew down and transitioned to training and advising at the regional and institutional level, the ANDSF struggled to succeed. General Joseph Dunford warned the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 2014 that upon coalition troop withdrawal, the "Afghan security forces will begin to deteriorate.... I think the only debate is the pace of that deterioration." |7|

It was not until 2015 that the United States and NATO prioritized security sector governance and defense institution building over improving the fighting capabilities of the force. Prior to 2015, developing Afghan ministerial capability in the security sector was primarily focused on governing initiatives that would improve the combat effectiveness of the force, often postponing the governing functions that are critical to improving accountability, oversight, professional development, and command of subordinate units.

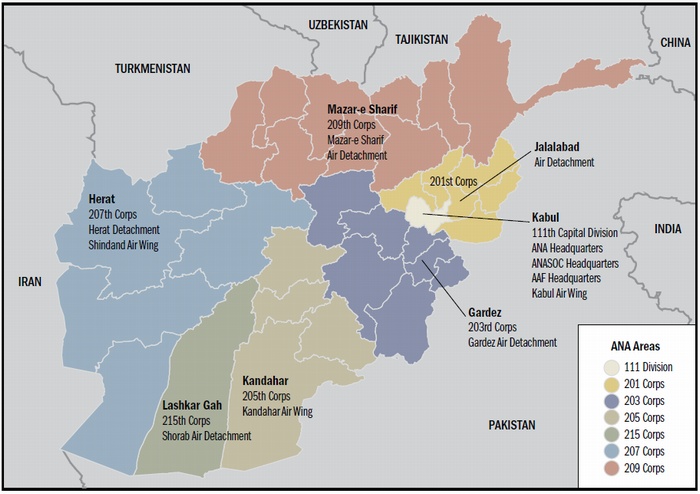

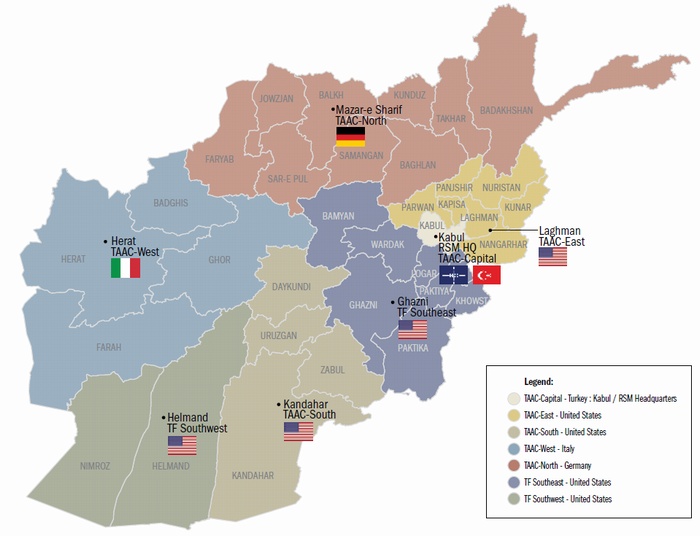

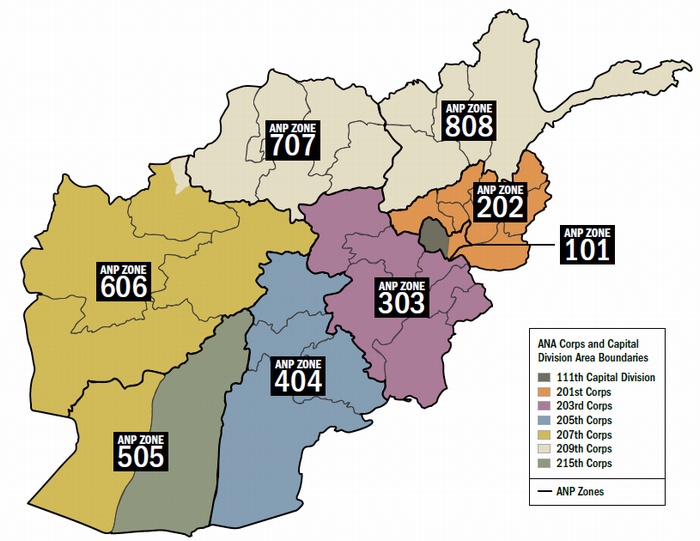

Starting in January 2015, U.S. and NATO forces have provided train, advise, and assist support to the ANDSF at the ANA corps level, the ANP zone level, and within the Ministries of Defense and Interior. Four regional train, advise, and assist commands (TAAC) provide routine support to ANDSF units in close proximity and will "fly-to-advise" to more remote locations, as needed. This posture has significantly decreased U.S. "touch-points" with ANDSF units, causing the United States to rely on ANDSF information to understand the forces' needs and struggles. Leaving some units uncovered, without regular U.S. advisors, proved disastrous in the summer of 2015, as the ANA 215th Corps in Helmand completely collapsed and had to be reconstituted.

Even with improved U.S. SSA efforts, corruption within the security forces and associated ministries continues to corrode the ANDSF's force readiness and battlefield performance. By 2013, corruption was officially recognized as a critical threat to U.S. objectives in Afghanistan. Despite consistent reports of rampant corruption, U.S. security-related aid was provided with little oversight or accountability. According to Lieutenant General Todd Semonite, former commanding general of CSTC-A, the United States had "no conditions" on funds flowing through CSTC-A to the Afghan defense and interior ministries prior to 2014. |8| SIGAR noted in a 2015 report to Congress that, even with conditions on U.S. aid, Afghan leaders "may construct compliance charades like enacting high-sounding but unenforced laws and conceal day-to-day practices." Today, the Ministry of Interior (MOI) is widely accepted as one of the most corrupt institutions in Afghanistan. In May 2017, at the Third Annual European Union Anti-Corruption Conference, President Ashraf Ghani publicly admitted that "the Ministry of Interior is the heart of corruption in the security sector." |9|

As security in Afghanistan continues to deteriorate, force protection requirements have increased, ultimately restricting U.S. advisors' ability to operate. Civilian advisors, once able to drive themselves to the Ministry of Defense (MOD) and MOI, are now forced to move with armed guards, in convoys, or even by helicopter. Expeditionary Advisory Packages–the U.S. military's way of reaching remote units–typically travel in large armored convoys supported by U.S. air power. In these packages, advisor to security personnel ratios can be as high as 1 to 3. President Ghani is attempting to restructure the ANDSF to optimize offensive capabilities and to reverse the eroding stalemate, but with the U.S. military confined to large bases and the civilian advisory mission largely stuck behind U.S. Embassy Kabul's walls, there are limits on what can be achieved.

LESSONS

This report identifies 11 lessons to inform U.S. policies and actions at the onset of and throughout a contingency operation.

1. The U.S. government is not well organized to conduct SSA missions in post-conflict nations or in the developing world because our doctrine, policies, personnel, and programs are insufficient to meet mission requirements and expectations.

2. SSA cannot employ a one-size-fits-all approach; it must be tailored to a host nation's context and needs. Security force structures and capabilities will not outlast U.S. assistance efforts if the host nation does not fully buy into such efforts and take ownership of SSA programs.

3. Senior government and nongovernment leaders in post-conflict or developing-world countries are likely to scrimmage for control of security forces; SSA missions should avoid empowering factions.

4. Western equipment and systems provided to developing-world militaries are likely to create chronic, high-cost dependencies.

5. Security force assessment methodologies are often unable to evaluate the impact of intangible factors such as leadership, corruption, malign influence, and dependency, which can lead to an underappreciation of how such factors can undermine readiness and battlefield performance.

6. Developing and training a national police force is best accomplished by law enforcement professionals in order to achieve a police capability focused on community policing and criminal justice.

7. To improve the effectiveness of SSA missions in coalition operations, the U.S. government must acknowledge and compensate for any coalition staffing shortfalls and national caveats that relate to trainers, advisors, and embedded training teams.

8. Developing foreign military and police capabilities is a whole-of-government mission.

9. In Afghanistan and other parts of the developing world, the creation of specialized security force units often siphons off the conventional force's most capable leaders and most educated recruits.

10. SSA missions must assess the needs of the entire spectrum of the security sector, including rule of law and corrections programs, in addition to developing the nation's police and armed forces. Synchronizing SSA efforts across all pillars of the security sector is critical.

11. SSA training and advising positions are not currently career enhancing for uniformed military personnel, regardless of the importance U.S. military leadership places on the mission. Therefore, experienced and capable military professionals with SSA experience often choose non-SSA assignments later in their careers, resulting in the continual deployment of new and inexperienced forces for SSA missions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

SIGAR recommends the following actions that can be undertaken by Congress or executive branch agencies to inform U.S. security sector assistance efforts at the onset of and throughout reconstruction efforts, and to institutionalize the lessons learned from the U.S. experience in Afghanistan. The first set of recommendations is applicable to any current or future contingency operation and the second set of recommendations is specific to Afghanistan.

Legislative Recommendations

1. The U.S. Congress should consider (1) establishing a commission to review the institutional authorities, roles, and resource mechanisms of each major U.S. government stakeholder in SSA missions, and (2) evaluating the capabilities of each department and military service to determine where SSA expertise should best be institutionalized.

2. The U.S. Congress should consider mandating a full review of all U.S. foreign police development programs, identify a lead agency for all future police development activities, and provide the identified agency with the necessary staff, authorities, and budget to accomplish its task.

Executive Agency Recommendations

1. Department of Defense (DOD) and State SSA planning must include holistic initial assessments of mission requirements that should cover the entire range of the host nation's security sector.

2. DOD and State should coordinate all U.S. security sector plans and designs with host-nation officials prior to implementation to deconflict cultural differences, align sustainability requirements, and agree to the desired size and capabilities of the force. DOD and State should also engage with any coalition partners to ensure unity of effort and purpose.

3. DOD, in partnership with State, should reinforce with host-nation leaders that the United States will only support the development of a national security force that is inclusive of the social, political, and ethnic diversity of the nation.

4. To prevent the empowerment of one political faction or ethnic group, DOD, in coordination with State and the intelligence community, should monitor, evaluate, and assess all formal and informal security forces operating within a host nation. DOD should also identify and monitor both formal and informal chains of command and map social networks of the host nation's security forces. DOD's intelligence agencies should track and analyze political associations, biographical data, and patronage networks of senior security officials and political leadership.

5. DOD, State, and other key SSA stakeholders should enhance civilian and military career fields in security sector assistance, and create personnel systems capable of tracking employee SSA experience and skills to expedite the deployment of these experts.

6. DOD and State should mandate professional development and training for all civilian and military members involved in SSA activities, as well as review curricula from the current training programs to align training with mission requirements and fully prepare deploying SSA personnel.

7. To overcome staffing shortages within a coalition, DOD and State should bolster political and diplomatic efforts to ensure better compliance with agreed-upon resource contributions from partner nations and, if unsuccessful and unable to fill the gaps, reassess timeframes and anticipated outcomes to accommodate new realities.

DOD-Specific Recommendations

1. Prior to the initiation of an SSA mission–and periodically throughout the mission–DOD should report to the U.S. Congress on its assessments of U.S. and host-nation shared SSA objectives, alongside an evaluation of the host nation's political, social, economic, diplomatic, and historical context, to shape security sector requirements.

2. DOD should lead the creation of new interagency doctrine for security sector assistance that includes best practices from Afghanistan, Iraq, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Vietnam.

3. DOD should review the evolution of command structures and assessment methodologies used in Afghanistan and Iraq to determine best practices and a recommended framework to be applied to future SSA missions. DOD should design new monitoring and evaluation tools capable of analyzing both tangible and intangible factors affecting force readiness.

4. DOD should conduct a human capital, threat, and material needs assessment and design a force accordingly, with the appropriate systems and equipment.

5. When creating specialized units such as special forces, DOD should submit human capital assessments and sustainability analyses for both the specialized and conventional forces to the House and Senate Appropriations and Armed Services Committees. Force capability assessments must determine the best course of action, including redesigning requirements for each unit.

6. DOD should diversify the leadership assigned to develop foreign military forces, to include civilian defense officials with expertise in the governing and accountability systems required in a military institution.

7. DOD and the military services should institutionalize security sector assistance and create specialized SSA units that are fully trained and ready to deploy rapidly for immediate SSA missions. DOD should create an institution responsible for coordinating and deconflicting SSA activities between the services and greater DOD, provide pre-deployment training, and serve as

the lead proponent for security sector governance requirements, including defense institution building.

Afghanistan-Specific Recommendations

While the United States continues to support the development and professional-ization of the ANDSF, there are several actions that can be taken now to improve our SSA efforts.

Executive Agency Recommendations

1. Realign the U.S. advisor mission to meet the operational and organizational roles and responsibilities of the ANDSF, MOD, and MOI.

2. Recreate proponent leads for the ANA and ANP.

3. Create a rear element to provide persistent and comprehensive support to CSTC-A and the TAACs.

4. Synchronize troop decisions with NATO force generation conference schedules and begin discussions for post-2020 NATO support to Afghanistan.

5. Mandate SSA pre-deployment training at service-level training centers.

6. Create incentives for military and civilian personnel with expertise in SSA.

7. Improve ANDSF governing, oversight, and accountability systems.

8. Impose stringent conditionality mechanisms to eliminate the ANDSF's culture of impunity.

9. Develop a civilian cadre of security sector governance personnel at MOD and MOI.

10. Institutionalize rotational schedules that allow for continuity in mission and personnel.

11. Increase civilian advisors to the ANDSF, MOD, and MOI.

DOD-Specific Recommendations

1. Implement best practices and develop mitigation strategies for the Afghan Air Force recapitalization.

2. Conduct a human capital assessment of the ANDSF conventional and special forces.

3. Review combat and logistics enabler support to the ANA.

4. Increase advisory capacity in ANA military academies and ANA and ANP training centers.

5. Expand the train, advise, and assist mission below the corps level.

6. Consider security requirements, such as guardian angels for trainers and advisors, when making decisions on contributing additional troops.

7. Ensure that the necessary technical oversight is available when maintenance or training tasks are delegated to support contracts.

8. Consider deploying law enforcement professionals to advise the ANP.

Chapter 1. Introduction

The development of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) is a cornerstone of the overall U.S. policy in Afghanistan and a key requirement of the U.S. strategy to transition security to the Afghan government. Since 2002, the ANDSF has been raised, trained, equipped, and deployed to secure Afghanistan from internal and external threats, as well as to prevent the reestablishment of terrorist safe havens. To achieve this outcome, the United States devoted over $70 billion (60 percent) of its Afghanistan reconstruction funds to building the ANDSF through 2016, and continues to commit over $4 billion per year to that effort.

This lessons learned report draws important lessons from the U.S. experience building the ANDSF since 2002. These lessons are relevant to ongoing efforts in Afghanistan, where the United States will likely remain engaged in security sector assistance (SSA) efforts to support the ANDSF through at least 2020. In addition, the United States currently participates in efforts to build other developing-world security forces as a key tenet of its national security strategy, an effort we anticipate will continue. The report further provides timely and actionable recommendations intended to improve U.S. operations and outcomes in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

This report is divided into nine chapters. After the introductory section, chapters two through five characterize the different eras of U.S. efforts to design, train, advise, assist, and equip the ANDSF and describe how these efforts waxed and waned within the policy priorities of the United States and other key donors. The chapters chart the evolution of the mission from the United States' initial agreement to serve as the lead nation for developing the Afghan National Army (ANA), to later assuming a level of ownership for the success of the Afghan military and police forces, to ultimately making their development a critical precondition for reducing U.S. and coalition support over time. These sections note how the U.S. government was ill-prepared to develop a national security force in a post-conflict nation; the changing resource requirements for ANDSF personnel, equipment, and funding; and the inherent tensions within and between the U.S. government and the international coalition.

Chapter six provides a detailed analysis of cross-cutting issues affecting ANDSF development. These issues impacted both military and police development and were a persistent challenge from the beginning of the U.S. effort. They include corruption, illiteracy, the role of women, the provision of weapons and equipment, high levels of ANDSF attrition, and the annual rotation of U.S. advisors and trainers.

Chapters seven through nine constitute the report's conclusion. Chapter seven outlines in depth the key findings from our analysis of the U.S. efforts to develop the ANDSF. Chapter eight provides the lessons derived from this analysis. Chapter nine offers recommendations for improving security sector assistance efforts in Afghanistan and future contingency operations.

The report identifies 12 key findings regarding the U.S. experience developing the ANDSF:

1. The U.S. government was ill-prepared to conduct SSA programs of the size and scope required in Afghanistan. The lack of commonly understood interagency terms, concepts, and models for SSA undermined communication and coordination, damaged trust, intensified frictions, and contributed to initial gross under-resourcing of the U.S. effort to develop the ANDSF.

2. Initial U.S. plans for Afghanistan focused solely on U.S. military operations and did not include the construction of an Afghan army, police, or supporting ministerial-level institutions.

3. Early U.S. partnerships with independent militias–intended to advance U.S. counterterrorism objectives–ultimately undermined the creation and role of the ANA and Afghan National Police (ANP).

4. Critical ANDSF capabilities, including aviation, intelligence, force management, and special forces, were not included in early U.S., Afghan, and NATO force-design plans.

5. The United States failed to optimize coalition nations' capabilities to support SSA missions in the context of international political realities. The wide use of national caveats, rationale for joining the coalition, resource constraints and military capabilities, and NATO's force generation processes led to an increasingly complex implementation of SSA programs. This resulted in a lack of an agreed-upon framework for conducting SSA activities.

6. Providing advanced Western weapons and management systems to a largely illiterate and uneducated force without appropriate training and institutional infrastructure created long-term dependencies, required increased U.S. fiscal support, and extended sustainability timelines.

7. The lag in Afghan ministerial and security sector governing capacity hindered planning, oversight, and the long-term sustainability of the ANDSF.

8. Police development was treated as a secondary mission for the U.S. government, despite the critical role the ANP played in implementing rule of law and providing local-level security nationwide.

9. The constant turnover of U.S. and NATO trainers impaired the training mission's institutional memory and hindered the relationship building required in SSA missions.

10. ANDSF monitoring and evaluation tools relied heavily on tangible outputs, such as staffing, equipping, and training levels, as well as subjective evaluations of leadership. This focus masked intangible factors, such as corruption and will to fight, which deeply affected security outcomes and failed to adequately factor in classified U.S. intelligence assessments.

11. Because U.S. military plans for ANDSF readiness were created in an environment of politically constrained timelines–and because these plans consistently underestimated the resilience of the Afghan insurgency and overestimated ANDSF capabilities–the ANDSF was ill-prepared to deal with deteriorating security after the drawdown of U.S. combat forces.

12. As security deteriorated, efforts to sustain and professionalize the ANDSF became secondary to meeting immediate combat needs.

WHY POLICY MAKERS SHOULD CARE ABOUT SECURITY SECTOR ASSISTANCE

A fully capable ANDSF that is able to secure Afghanistan from internal and external threats and prevent the re-establishment of terrorist safe havens is a U.S. national security objective. Despite U.S. government expenditures of more than $70 billion in security sector assistance to design, train, advise, assist, and equip the ANDSF, the Afghan security forces are not yet capable of securing their own nation. Learning what has worked well–or not–over the past 16 years is important to improving ongoing efforts to create a capable ANDSF, as well as ensuring that future SSA efforts achieve their objectives.

In general, security sector assistance to foreign governments is used to meet U.S. national security objectives and increase U.S. influence globally. The United States aims to empower partner nations to address regional and national threats without a large deployment of U.S. combat forces. The 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance noted that "building partner capacity" is a key component of defense planning and will be used as a means of decreasing Department of Defense (DOD) budgets over time. |10| According to media reporting, a 2009 private White House briefing estimated the cost of deploying one U.S. soldier to Afghanistan to be about $1 million per year. |11| While $70 billion for SSA efforts over a 14-year period is a significant amount of money, that same amount equals the deployment of 70,000 U.S. soldiers to Afghanistan for only a single year, making SSA a truly cost-effective option.

While the U.S. government has a number of individual department and agency initiatives to improve SSA programs, it currently lacks a comprehensive, whole-of-government approach and coordinating body to manage implementation and provide oversight of these programs. In 2010, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates described "America's interagency toolkit" for building the security capacity of partner nations as a "hodgepodge of jerry-rigged arrangements constrained by a dated and complex patchwork of authorities, persistent shortfalls in resources, and unwieldy processes." |12| For example, in 2016 the RAND Corporation identified 106 "core" DOD security cooperation statutes within Title 10 of the U.S. Code. That same year, the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) identified 24 programs in seven different U.S. agencies responsible just for police development. |13|

"America's interagency toolkit" for building the security capacity of partner nations was a "hodgepodge of jerry-rigged arrangements constrained by a dated and complex patchwork of authorities, persistent shortfalls in resources, and unwieldy processes."

–U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert GatesIn the 2016 Brussels Agreement, the United States committed to supporting the ANDSF through 2020. The U.S. administration is currently deliberating a new Afghanistan strategy, to include potentially long-term support to training, advising, and assisting the ANDSF. It is therefore necessary to identify, understand, and apply U.S., NATO, and Afghan lessons learned over the last 15 years of SSA efforts to position the United States to meet its national security objectives in Afghanistan, and to eventually support the exit of U.S. combat forces from that nation.

THE COMPLEXITIES OF THE U.S. SECURITY SECTOR ASSISTANCE FRAMEWORK

The legal and institutional framework of SSA originated in congressional documents, legislation, and executive orders beginning in the late 1940s. The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 cemented the Secretary of State's policy and oversight role in SSA, with DOD serving as the primary executor. Starting in the 1980s, Congress provided DOD with its own SSA authorities under Title 10 and the annual National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAA). These authorities increased through the 1990s, ultimately giving DOD the ability to independently fund security assistance programs for counternarcotics, humanitarian assistance, nonproliferation, and counterterrorism, each with State's concurrence. |14|

Following the mass casualty terror attacks in the U.S. homeland on September 11, 2001, and the eventual U.S. commitment to reconstruct both the Afghan and Iraqi security forces, Congress substantially increased State and DOD authorities to train, advise, assist, and equip foreign security forces. Due to State's limited number of personnel and ability to oversee security programs, DOD's role ultimately increased beyond State's oversight capacity. To meet the growing demand for SSA activities, DOD's authorities and responsibilities were increased. |15|

Security Sector Assistance Security sector assistance is defined in the 2013 Presidential Policy Directive 23 (PPD 23) as "policies, programs, and activities the United States uses to: (1) engage with foreign partners and help shape their policies and actions in the security sector; (2) help foreign partners build and sustain the capacity and effectiveness of legitimate institutions to provide security, safety, and justice for their people; and (3) enable foreign partners to contribute to efforts that address common security challenges." |16|

Within DOD alone, there are programs for building partner capacity, security assistance, security sector assistance, security force assistance, global train and equip missions, and defense institution building (table 1 on the next page). Currently, DOD views each of these separate programs as fitting under the umbrella of "security cooperation," a term used when the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) administers defense equipment, military training, and other defense-related services. The purpose of security cooperation, as defined by DOD, is to "build defense relationships that promote specific U.S. security interests, develop allied and friendly military capabilities for self-defense and multinational operations, and provide the U.S. with peacetime and contingency access to a host nation." |17| With the exception of defense institution building, each of these programs largely focuses on improving the effectiveness of fighting forces, without addressing the governance and civilian authorities that oversee them.

TABLE 1

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE SECURITY SECTOR ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS Program Description Security Cooperation According to DSCA, security cooperation "comprises all activities undertaken by [DOD] to encourage and enable international partners to work with the United States to achieve strategic objectives" Additionally security cooperation promotes specific U.S. security interests, develops allied and friendly military capabilities, and provides U.S. forces with peacetime and contingency access to host nations. Security Sector Assistance (SSA) DOD uses the 2013 definition of SSA established in PPD 23. SSA refers to the policies, programs, and activities the United States uses to engage with foreign partners to assist them with their security sector development; this includes building and sustaining partner nations' security capacities and enabling foreign partners to contribute to common security challenge efforts. SSA is intended to complement U.S. national security and foreign assistance objectives. Security Force Assistance (SFA) SFA entails all DOD activities that support the development of the capacity and capability of foreign security forces and their supporting institutions. SFA focuses on helping foreign security forces independently make decisions and conduct operations. Also, SFA seeks to support the professionalization and sustainability of foreign security forces. Building Partner Capacity (BPC) DSCA is responsible for managing the execution of a wide array of Title 10 and Title 22 programs designed to advance partner nation capacity and capabilities through the provision of training and equipment. Also, through Title 10 humanitarian-related programs, DOD seeks to achieve national security objectives by building military-civilian relations. DSCA houses BPC programs within the Directorate of BPC, which is organized into separate divisions: equipping division; humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, and mine action division; and training division. A mixture of DOD Foreign Military Financing and Foreign Military Sales-funded personnel comprise the staffing for these programs. Train and Equip Train and equip programs are established in accordance with Section 1206 of the NDAA to build the capacity of foreign military forces. The Secretary of Defense, with concurrence from the Secretary of State, supports and conducts various programs to build the capacity of a foreign military force so the country can sustain its forces and defend itself without assistance. Defense Institution Building (DIB) DOD Directive 5205.82, issued in January 2016, describes DIB as "security cooperation activities that empower partner nation defense institutions to establish or re-orient their policies and structures to make their defense sector more transparent, accountable, effective, affordable, and responsive to civilian control." DIB increases the sustainability of other DOD security cooperation programs and is typically conducted at the ministerial, general, joint staff, and military headquarters levels. Defense institutions include the people, organizations, rules, norms, values, and behaviors that enable a defense enterprise to function with proper oversight, governance, and management. Ministry of Defense Advisors (MODA) Piloted in July 2010, this effort partnered DOD civilian experts with foreign defense and security officials to build core competencies in areas such as strategy and policy, human resources management, acquisition and logistics, and financial management. Congress authorized the Secretary of Defense, with concurrence from the Secretary of State, to assign DOD civilian employees as advisors to the ministries of defense of foreign countries in the fiscal year (FY) 2012 NDAA. In Afghanistan, where the program was first implemented, MODA sought to address past concerns regarding advisors' lack of expertise. Defense Institutional Reform Initiative (DIRI) DIRI is a "global institutional capacity-building program that supports partner nation ministries of defense (MOD) and related institutions to address capacity gaps" To address partner nation weaknesses and shortfalls, DIRI provides subject matter experts to work with partner nation leaders. Source: Defense Security Cooperation Agency, "Directorate of Building Partnership Capacity," http://www.dsca.mil/about-us/programs-pgm (accessed February 7, 2017); DSCA, "Security Cooperation Overview and Relationships," http://www.samm.dsca.mil/chapter/chapter-1 (accessed February 7, 2017); GAO, Security Force Assistance: The Army and Marine Corps Have Ongoing Efforts to Identify and Track Advisors, but the Army Needs a Plan to Capture Advising Experience, GAO-14-482, July 11, 2014, p. 1; DSCA, "Security Force Assistance (SFA)," http://samm.dsca.mil/glossary/security-force-assistance-sfa (accessed February 7, 2017); DOD, "Instruction 5000.68 - Security Force Assistance," October 27, 2010, p. 2; DOD, "Directive 5205.82 - Defense Institution Building (DIB)," January 27, 2016, p. 13; GAO, Building Partner Capacity: DOD Should Improve Its Reporting to Congress on Challenges to Expanding Ministry of Defense Advisors Program, GAO-15-279, February 2015, pp. 1-2; DODIG, Defense Institution Reform Initiative Program Elements Need to Be Defined, DODIG-2013-019, November 9, 2012, p. 2; DSCA, "Defense Institutional Reform Initiative (DIRI)," http://www.dsca.mil/programs/defense-institutional-reform-initiative (accessed February 8, 2017); DOD, "Directive 5132.03 - DOD Policy and Responsibilities Relating to Security Cooperation," December 29, 2016, p. 17; White House, "Fact Sheet: U.S. Security Sector Assistance Policy," April 5, 2013; National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-163, § 1206; DOD, "Instruction 5111.19 - Section 1206 Global Train-and-Equip Authority," July 26, 2011.

It was not until 2008 that DOD began two small programs aimed specifically at improving security sector governance: the Defense Institutional Reform Initiative (DIRI) within the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) for Security Cooperation, and the Ministry of Defense Advisors (MODA) program, aligned under DSCA. To date, DOD lacks a coordinating and oversight institution responsible for all defense and military security assistance activities conducted independently by the military services, Joint Staff, DSCA, and OSD.

Security sector governance is the transparent, accountable, and legitimate management and oversight of security policy and practice.

State's SSA authorities are largely derived from Title 22 of the U.S. Code. For State, the security assistance portfolio has no formal definition, but rather consists of six budget accounts under the header "International Security Assistance." |18| State's DOD-implemented programs, such as Foreign Military Sales (FMS), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), and International Military Education and Training (IMET), are conducted under State's Title 22 authorities. State also administers its own programs authorized by Title 22, including International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE); Nonproliferation, Anti-Terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR); and Peacekeeping Operations (table 2). While DOD categorizes its efforts under the umbrella of security cooperation, State defines all support to foreign military and security forces as security sector assistance.

TABLE 2

DEPARTMENT OF STATE SECURITY SECTOR ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS Program Description Foreign Military Sales (FMS) FMS is a form of security assistance authorized by the Arms Export Control Act (AECA) intended to strengthen U.S. security and promote world peace. The Secretary of State determines which countries are eligible to participate in FMS and the Secretary of Defense executes the programs. FMS is conducted through formal contracts or agreements between the U.S. government and an authorized foreign purchaser through a seven-step process. Foreign Military Financing (FMF) FMF is also authorized through the AECA and provides the authority to finance procurement of defense items for foreign countries and international organizations. FMF gives eligible partner nations the ability to purchase U.S. defense articles, training, and services through FMS or foreign military financing of direct commercial contracts. Similar to the FMS program, the Secretary of State determines which countries are eligible and the Secretary of Defense executes the programs. FMF funds are appropriated by Congress through the Department of State Foreign Operations and Related Programs Appropriation Act. International Military Education and Training (IMET) According to a 2014 joint report to Congress on FMF; State and DOD agreed that IMET was a "low-cost, highly effective component of U.S. security assistance" To address security issues and improve defense cooperation between the United States and other countries, IMET seeks to establish regional stability through cohesive military-to-military relations. Additionally, IMET provides training to foreign military forces and civilian personnel to reinforce their adherence to democratic values within their government and military. International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) In partnership with DOD, INCLE seeks to combat international drug trafficking, terrorist organizations, and other transnational crime groups through the training of foreign law enforcement and security institutions. INCLE provides training and other essential support for foreign governments to identify, confront, and disrupt the operations of illicit groups before they become a U.S. national security threat. INCLE funds are focused on areas where security situations are most dire and where U.S. resources are used in tandem with host country government strategies. Nonproliferation, Anti-Terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR) NADR seeks to counter foreign terrorist fighters, destroy small arms, clear unexploded ordnance, and address other critical, security-related issues. The programs within NADR primarily entail working with other countries to reduce transnational threats. Peacekeeping Operations (PKO) PKO funds "support multilateral peacekeeping and regional stability operations that are not funded through the [United Nations]" PKO seeks to address gaps in capabilities to allow countries and regional organizations to participate in a variety of peacekeeping operations, as well as to reform security forces in a post-conflict environment. Source: Defense Institute of Security Cooperation Studies, "Chapter 5: Foreign Military Sales Process," Green Book, January 2017, pp. 5-1, 5-2; DSCA, "Foreign Military Financing," http://www.dsca.mil/programs/foreign-military-financing-fmf (accessed February 8, 2017); House Committee on Appropriations, State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Appropriations Bill, H.R. Rep. 114-154 (June 15, 2015), pp. 42-49; DOS and DOD, Foreign Military Training Joint Report to Congress, October 30, 2014, pp. II-2, II-3; DOS, "Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs Program and Budget Guide: Fiscal Year 2012 Budget," https://www.state.gov/j/inl/rls/rpt/pbg/fy2012/185676.htm (accessed April 20, 2017); DOS, "Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs Program and Budget Guide: Fiscal Year 2012 Budget," https://www.state.gov/j/inl/rls/rpt/pbg/fy2012/185676.htm (accessed April 20, 2017); DOS, "Peacekeeping Operations Account Summary," https://www.state.gov/t/pm/ppa/sat/c14563.htm (accessed February 8, 2017).

In an effort to address the complexity of U.S. SSA programs, the administration of President Barack Obama ordered a top-down review of all security assistance programs and authorities in 2009. As a result of this review, the White House issued PPD 23 in April 2013, mandating an overhaul of SSA policy. PPD 23 required establishing a new interagency framework for planning, implementing, assessing, and overseeing SSA to foreign governments and international organizations. |19| The White House Fact Sheet for PPD 23 stated that SSA programs were aimed at "strengthening the ability of the United States to help allies and partner nations to build their own security capacity consistent with the principles of good governance and rule of law." A further goal of PPD 23 was to promote "universal values, such as good governance, transparent and accountable oversight of security forces, rule of law, transparency, accountability, delivery of fair and effective justice, and respect for human rights." |20|

Congress took several actions in the FY 2017 NDAA to enhance and improve DOD's authorities to conduct SSA. In Section 1204, Congress mandated an evaluation of DOD's framework for security cooperation activities by an independent entity, which must submit its recommendations to Congress by November 1, 2018. Congress further recommended in Section 1205 that the Secretary of Defense "develop and maintain an assessment, monitoring, and evaluation framework for security cooperation with foreign countries to ensure accountability and foster implementation of best practices." |21| Recognizing that DOD has historically prioritized improving the kinetic capabilities of combat forces and placed less attention on the governing institutions overseeing them, Section 1233 stated that "the Secretary shall certify ... a program of institutional capacity building ... to enhance the capacity of such foreign country to exercise responsible civilian control of the national security forces of such foreign country" as a part of future security assistance programs. |22| State, Department of Justice (DOJ), and other non-DOD SSA stakeholders have not been subject to the same scrutiny and review of SSA-related authorities and capabilities.

Complexities Enhanced: Security Sector Assistance within NATO SSA in Afghanistan was a "whole-of-governments" effort, as programs and initiatives were divided among the United States, NATO, and non-NATO coalition partners, fundamentally increasing the complexity of the mission. After 9/11, NATO invoked Article 5 of the alliance's charter for the first time, leading to the creation of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) as the first NATO expeditionary mission. |23| While some U.S. military and civilian personnel had prior experience operating under a NATO charter, for example, in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Haiti, the United States had never partnered with NATO on a mission of the size and scale required in Afghanistan.

Understanding NATO processes, capabilities, and authorities was a challenge for U.S. officials, in particular because these activities often did not align with U.S. doctrine, policies, and authorities, as was the case with SSA missions. |24| Furthermore, the deployment of NATO advisors and trainers was often held up by NATO's force-generation processes, and the advisory missions were therefore chronically understaffed and under-resourced. Due to the lack of standardization in NATO deployments, assigned trainers and advisors were beholden to their individual country's rules, laws, and caveats; as a result, NATO forces lacked a uniform mission and purpose. |25| In addition, chronic issues of interoperability and information sharing unnecessarily complicated the mission. All of these differences led to the creation of an unsynchronized force and limited the development of the ANDSF. |26| To this day, the United States and its NATO partners lack a commonly shared doctrine or policy for conducting security sector assistance missions.

CHAPTER 2

2001-2003:

BUILDING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR TH AFGHAN NATIONAL SECURITY FORCESEARLY U.S. EFFORTS DID NOT INCLUDE SECURITY FORCE DEVELOPMENT

On 9/11, the U.S. military had no plans prepared and readily available for operations in Afghanistan. As a result, the U.S. response was initially led by Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operators, leveraging intelligence assets and personal relationships with anti-Taliban militias, mainly the Northern Alliance faction. Small teams of U.S. Special Forces quickly deployed to Afghanistan and partnered with CIA and Northern Alliance teams to target Taliban positions and track and attack al-Qaeda leaders. |27| A little over two weeks after the 9/11 attacks, the White House published its "Declaratory Policy on Afghanistan," describing the United States' focused goal in Afghanistan as "simple: eradicate the terrorism that led to the strikes that killed citizens of 78 countries on September 11." |28|

On October 7, 2001, with military plans finalized, President George Bush authorized Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and its strikes on al-Qaeda training camps and Taliban military installations. In his address to the nation that evening, the president stated, "Today we focus on Afghanistan, but the battle is broader." |29| Based on the need for a rapid response to the 9/11 attacks, DOD planners focused on kinetic operations and had little time to plan for post-conflict reconstruction, including building a national army and police force. The Bush administration, staunchly opposed to nation building, drafted a document for discussion among senior officials that stated the United States "should not commit to any post-Taliban military involvement, since the U.S. will be heavily engaged in anti-terrorism efforts worldwide." |30| The U.S.-partnered operations with the Northern Alliance and U.S. air superiority quickly overwhelmed the Taliban battle lines, forcing large units to surrender or withdraw to Taliban-controlled pockets in the south and east of Afghanistan. Senior U.S. officials rebuffed Taliban surrender and reconciliation overtures to Afghan factional leaders, preferring a military defeat of the Taliban. |31| On December 7, 2001, Taliban Ambassador to Pakistan Mullah Salam Zaeef announced the Taliban's strategic withdrawal from Afghanistan. |32|

Operation Enduring Freedom vs. the International Security Assistance Force From 2001 to 2015, two separate and independent operations were being conducted simultaneously in Afghanistan: the U.S.-led Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and the NATO-led and UN-approved International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). OEF was principally designed to target al-Qaeda and Taliban elements as part of the U.S. Global War on Terrorism, with a secondary mission of developing the ANA and eventually the police. With the primary U.S. focus on counterterrorism operations, senior U.S. officials believed that reconstruction of Afghanistan should be the responsibility of the international community.

UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1386 established ISAF in 2001. |33| ISAF was a NATO-led military mission responsible for stability and peacekeeping operations. According to the 2001 Bonn Agreement, ISAF was initially given the responsibility to assist and consult with the Afghan Interim Authority to maintain security in and around Kabul so that Afghan and UN personnel could work safely. |34| ISAF's other primary objectives were to build capacity in governance, reconstruct and develop the country, and conduct counternarcotics efforts. |35| To this day, the United States continues to operate an independent counterterrorism mission (Operation Freedom's Sentinel) in parallel with the NATO train, advise, and assist mission of Resolute Support.

THE AFGHAN SCRIMMAGE FOR POWER

After the Taliban's removal from power, anti-Taliban factions–predominantly the Shura-e Nazar (SEN) faction of the Northern Alliance–exploited this moment and quickly moved to control key security leadership positions (figure 1). With U.S. government support or, at best, indifference, the Northern Alliance stepped deftly into positions of authority across Kabul, forming a new government composed mostly of heavily armed, former Northern Alliance power brokers. |36| In Bonn, Germany, Afghan factions selected Hamid Karzai, a Pashtun tribesman from southern Afghanistan, as the leader of the Afghan Interim Authority (AIA). Hamid Karzai lacked a robust personal security force and relied heavily on U.S. Special Forces to move throughout Afghanistan. In exchange for political support at Bonn, Karzai appointed Northern Alliance leaders as the interim Ministers of Defense, Interior, and Foreign Affairs, resulting in their monopoly of power over the national security apparatus.

FIGURE 1

NORTHERN ALLIANCE DOMINATES SECURITY MINISTRIES

Source: Hamid Karzai (DOD photo by Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo); Fahim Khan (photo by Maj. William S. Wynn); Yunis Qanooni (photo by Michat Koziczyhski); Abdullah Abdullah (photo by Jessica Lea/DFID).

"Insecurity and the lack of law and order continue to impact negatively on the lives of Afghans every day whittling away at the support for the transitional process."

–UN Security CouncilFrom 2002 to 2003, the scrimmage for power among Afghan elites and competing local and regional militias posed the greatest threat to Afghan stability. In the north, Jumbesh-e Milli leader Abdul Rashid Dostum and Northern Alliance commander Atta Mohammad Noor engaged in regular armed clashes over control of Mazar-e Sharif and other key territories. In the west, Ismail Khan's fighters clashed with Amannullah Khan's militia for control over Herat City. |37| In an act of particularly brazen defiance, militia commander Pacha Khan Zadran shelled Gardez City in Paktia Province, killing dozens of civilians after a local shura refused Karzai's appointment of Zadran as the provincial governor. |38| Karzai, lacking his own national security forces, was unable to intervene and quell conflicts that affected the daily lives of the population, resulting in a loss of local support and momentum gained after the collapse of the Taliban government. |39| In early 2003, a UN Security Council report stated that "insecurity and the lack of law and order continue to impact negatively on the lives of Afghans every day, whittling away at the support for the transitional process." |40|

LEAD NATION SILOS: INTERNATIONAL COMMITMENT TO SECURITY SECTOR REFORM

In early 2002, the United States and its coalition partners concluded that the development of an internationally trained and professional Afghan national security force could serve as a viable alternative to the expansion of international forces in Afghanistan. |41| An indigenous force would also serve to expedite the reduction of international forces already in country. In April 2002, the Group of Eight (G8) nations met in Geneva, Switzerland, to map out divided responsibilities for security sector reform (SSR) in Afghanistan. Five independent silos with an appointed lead nation were created: military reform (United States), police reform (Germany), judicial reform (Italy), counternarcotics (United Kingdom), and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (Japan) (figure 2). |42| At a 2003 SSR conference in Kabul, Karzai announced that "security sector reform, in short, is the basic prerequisite to recreating the nation that today's parents hope to leave to future generations." |43|

Despite the U.S. government's commitment to help build the ANA, the U.S. national security team held divergent views on the required level of U.S. financial support. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld–an opponent of nation building–argued that the United States was spending billions of dollars "freeing Afghanistan" and that the U.S. position on financial support to the Afghan army "should be zero." |44| Secretary of State Colin Powell disagreed, arguing that "there can be no reconstruction in Afghanistan without security." |45| Powell even went so far as to say the United States should plan to be "heavily involved" in both the army and police reconstruction. |46|

FIGURE 2

LEAD NATIONS OF SECURITY SECTOR REFORM IN AFGHANISTAN

Source: GAO, Afghanistan Security: Efforts to Establish Army and Police Have Made Progress, but Future Plans Need to Be Better Defined, GAO-05-575, June 2005, p. 5.

Security Sector Coordinator In October 2002, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld selected General Karl Eikenberry to serve as the head of the Office of Military Cooperation-Afghanistan (OMC-A) and as Security Sector Coordinator (SSC). His job was to integrate Ministry of Defense (MOD) and ANA development and to synchronize the five-pillar international SSR process. Eikenberry would report through both DOD and State channels. His primary task was to "accelerate the development of a Security Sector Reform working group that would include the five lead nations, the Afghan government, and the [United Nations]." |47| Describing his initial planning for and execution of the SSC role, Eikenberry stated, "Overall, it might be termed exploratory learning because the many uncertainties of the Afghanistan mission added to the steepness of the learning curve. They included: (1) lack of doctrine for nation building on this level of destruction; (2) lack of cooperative agreements among the lead nations as to the scope of their efforts and willingness to cooperate; and (3) the unprecedented nature of building security sector in a nation that is so damaged after 30 years of civil war and humanitarian disaster." |48|

Security Sector Reform Senior Working Group at the British Embassy, summer 2003. (Photo by Jason Howk)

AFGHAN NATIONAL ARMY

Deciding on the Initial Design

With the Taliban removed from power, senior Afghan security officials– principally interim Minister of Defense Marshall Fahim Khan–advocated for a 200,000- to 250,000-member national transitional army staffed by "those who have participated in the liberation wars and have played a significant role in the defeat of the Taliban and al-Qaeda." |49| According to Khan's initial design in January 2002, the transitional Afghan Militia Force (AMF) would eventually be supplanted by a smaller, professionally trained force of 60,000 soldiers. |50| However, as security deteriorated, senior Afghan officials abandoned the smaller force design and sought a larger force to counter threats originating from Pakistan.

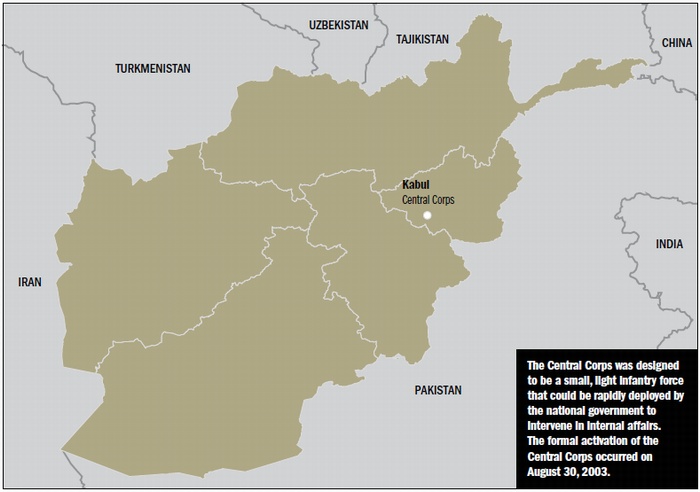

The U.S. design of the new national army did not match Khan's or that of other Afghan leaders. The U.S. goal was to minimize time, energy, resources, and commitment in Afghanistan by developing a smaller, Afghan-sustainable national security force. The United States believed that the greatest threat to Afghanistan's stability was factional fighting, not Pakistan, a country the United States viewed as a key ally in the Global War on Terrorism. The United States, therefore, believed Afghanistan needed a small, light infantry force that could be rapidly deployed by the national government to intervene in internal affairs. |51| According to an ANA design team chief, the initial U.S. plan was to develop one army corps, secure the upcoming presidential elections, and withdraw from Afghanistan by the end of 2004. |52|

The Afghan Militia Force After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, armed groups began to increase throughout Afghanistan. Each of these groups claimed a stake in the new Afghan Interim Government. |53| In 2002, private militias served as a transitional army called the Afghan Militia Force, under minimal control of the MOD. |54| The AMF was intended to provide security until a formal army could be created and supported.

The AMF faced numerous difficulties after its creation. Its military capability was poor due to lack of equipment, low discipline, and inefficiency. |55| AMF soldiers remained loyal to local warlords, commanders, and political parties. |56| Additionally, the AMF was under strength and most of the resources provided by the MOD were pocketed by the appointed commanders or redistributed among the troops. |57| There was also inflation of military ranks. According to Afghan army scholar Antonio Giustozzi, "The transitional army has one of the highest officer to soldier ratios in the world, estimated at 1 to 2.... Most armies are in the 1 to 12 or 13 range." |58| Because international donors did not want to keep the transitional army and refused to fund it, there was an attempt to move soldiers out of the AMF and into the ANA.

Given its position as the lead nation for military reconstruction, the United States was in a position to ensure that its preferred design for the new national army would take root. In December 2002, an agreement was finalized for a Ministry of Defense and an all-volunteer national army, with an eventual end-strength capped at 70,000 soldiers. |59| Furthermore, stakeholders agreed to a mandatory ethnic balance within the ANA that would be representative of the country as a whole. |60|

Despite agreeing to lead the development of the new Afghan army, the United States lacked an active and readily available military force, interagency doctrine, or model for reconstructing a foreign military at the scope and scale that Afghanistan required. Therefore, sticking with what they knew, senior U.S. military officers initially modeled the ANA on the U.S. Army's light infantry forces, despite the fact that Afghanistan lacked the infrastructure and logistical capabilities required for such a model. |61| The United States pushed for a standards-based, volunteer, ethnically diverse national army composed of civilian leaders, an officer corps, enlisted soldiers, and noncommissioned officers (NCO).

Civilian control of the military and a Western-style NCO corps were not a part of the history of the Afghan military forces, however, and were initially difficult for Afghan leaders to accept. The historical Soviet and Turkish influences had emphasized the development of officers, while neglecting the development of NCOs due to a draft or levy system that only required two-year assignments. Given this influence, many Afghan officials believed that only senior Afghan uniformed officers had the necessary background for leadership roles. U.S. General Eikenberry noted that Afghan leaders believed, "I have to be wearing a uniform. I don't like this idea of wearing civilian clothes and being in the Ministry of Defense." |62| Despite this tradition, the Afghans–capitulating to U.S. pressure for civilian military leadership–ultimately found a workable solution with the appointment of the former Northern Alliance commanding general Marshall Fahim Khan as the civilian Minister of Defense.

Training Commences: Focus On Light Infantry Brigades (May 2002-May 2003)

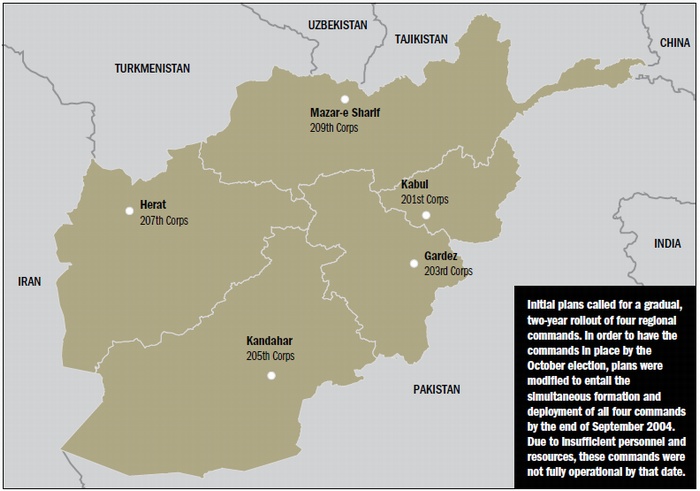

In May 2002, U.S. Special Forces officially commenced training the ANA. The first phase of training emphasized developing operational forces, specifically one light infantry corps in Kabul–the Central Corps–with expanded development to be determined at a later time (figure 3 on the next page). |63| The U.S. Special Forces trainers were fully prepared to execute their core competency, foreign internal defense (FID), to train small and inexpensive units of indigenous forces on light infantry tactics. |64| Thus, the Central Corps was designed to have limited combat power while relying on U.S. and international air power for missions requiring more lethal capabilities. |65| According to General Eikenberry, the Central Corps was intended to have "enough combat power that it would be able to act [at] the behest of the central government and move forward into an area of Afghanistan and impose its will upon any contending factional force." |66|