| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

10Feb17

U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues

Back to topContents

Introduction

Background: The Strategic TriadForce Structure and Size During the Cold War

Force Structure and Size After the Cold War

Current and Future Force Structure and SizeStrategic Nuclear Delivery Vehicles: Recent Reductions and Current Modernization Programs

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs)

Peacekeeper (MX)

Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles

Minuteman III

Minuteman Modernization Programs

Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD)The SSGN Program

Bombers Sustaining the Nuclear Weapons Enterprise

The Backfit Program

Basing Changes

Warhead Loadings

Modernization Plans and Programs

The Ohio Replacement Program (ORP) ProgramFigures

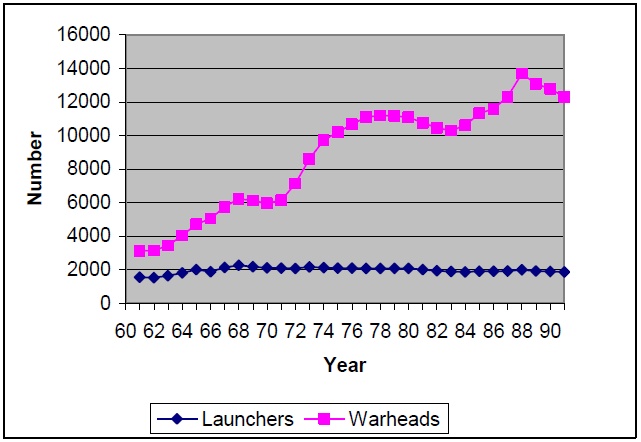

Figure 1. U.S. Strategic Nuclear Weapons: 1960-1990

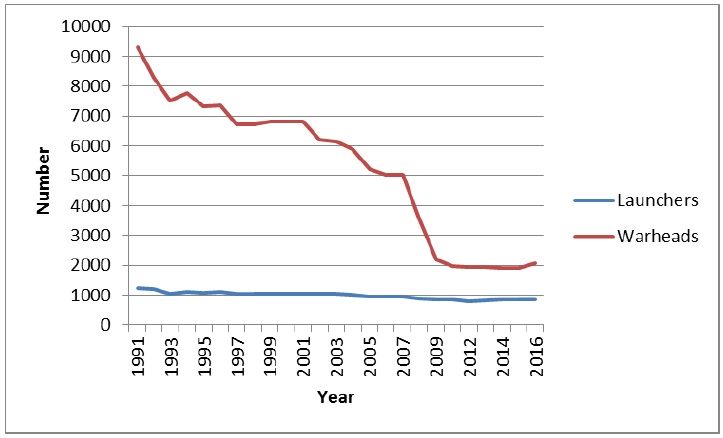

Figure 2. U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: 1991-2016Tables

Table 1. U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces Under START I and START II

Table 2. U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces under New START

Summary

Even though the United States is in the process of reducing the number of warheads deployed on its long-range missiles and bombers, consistent with the terms of the New START Treaty, it also plans to develop new delivery systems for deployment over the next 20-30 years. The 115th Congress will continue to review these programs, and the funding requested for them, during the annual authorization and appropriations process.

During the Cold War, the U.S. nuclear arsenal contained many types of delivery vehicles for nuclear weapons. The longer-range systems, which included long-range missiles based on U.S. territory, long-range missiles based on submarines, and heavy bombers that could threaten Soviet targets from their bases in the United States, are known as strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. At the end of the Cold War, in 1991, the United States deployed more than 10,000 warheads on these delivery vehicles. That number has declined to less than 1,500 deployed warheads today, and is slated to be 1,550 deployed warheads in 2018, after the New START Treaty completes implementation.

At the present time, the U.S. land-based ballistic missile force (ICBMs) consists of 414 land-based Minuteman III ICBMs, each deployed with one warhead. The fleet will decline to 400 deployed missiles, while retaining 450 launchers, to meet the terms of the New START Treaty. The Air Force is also modernizing the Minuteman missiles, replacing and upgrading their rocket motors, guidance systems, and other components, so that they can remain in the force through 2030. It plans to replace the missiles with a new Ground-based Strategic Deterrent around 2030.

The U.S. ballistic missile submarine fleet currently consists of 14 Trident submarines; each can carry up to 24 Trident II (D-5) missiles, although they will carry only 20 under the New START Treaty. The Navy converted 4 of the original 18 Trident submarines to carry non-nuclear cruise missiles. The remaining carry around 1,000 warheads in total; that number will decline as the United States implements the New START Treaty. Nine of the submarines are deployed in the Pacific Ocean and five are in the Atlantic. The Navy also has undertaken efforts to extend the life of the missiles and warheads so that they and the submarines can remain in the fleet past 2020. It is designing a new Columbia class submarine that will replace the existing fleet beginning in 2031.

The U.S. fleet of heavy bombers includes 20 B-2 bombers and 54 nuclear-capable B-52 bombers. The B-1 bomber is no longer equipped for nuclear missions. The fleet will decline to around 60 aircraft in coming years, as the United States implements New START. The Air Force has also begun to retire the nuclear-armed cruise missiles carried by B-52 bombers, leaving only about half the B-52 fleet equipped to carry nuclear weapons. The Air Force plans to procure both a new long-range bomber and a new cruise missile during the 2020s. DOE is also modifying and extending the life of the B61 bomb carried on B-2 bombers and fighter aircraft and the W80 warhead for cruise missiles.

The Obama Administration completed a review of the size and structure of the U.S. nuclear force, and a review of U.S. nuclear employment policy, in June 2013. This review has advised the force structure that the United States will deploy under the New START Treaty. It is currently implementing the New START Treaty, with the reductions due to be completed by 2018. The Trump Administration has indicated that it will conduct a new review of the U.S. nuclear force posture. Congress will review the Administration's plans for U.S. strategic nuclear forces during the annual authorization and appropriations process, and as it assesses U.S. plans under New START and the costs of these plans in the current fiscal environment. This report will be updated as needed.

Introduction

During the Cold War, the U.S. nuclear arsenal contained many types of delivery vehicles for nuclear weapons, including short-range missiles and artillery for use on the battlefield, medium-range missiles and aircraft that could strike targets beyond the theater of battle, short- and medium-range systems based on surface ships, long-range missiles based on U.S. territory and submarines, and heavy bombers that could threaten Soviet targets from their bases in the United States. The short- and medium-range systems are considered non-strategic nuclear weapons and have been referred to as battlefield, tactical, and theater nuclear weapons. |1| The long-range missiles and heavy bombers are known as strategic nuclear delivery vehicles.

In 1990, as the Cold War was drawing to a close and the Soviet Union was entering its final year, the United States had more than 12,000 nuclear warheads deployed on 1,875 strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. |2| As of July 1, 2009, according to the counting rules in the original Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), the United States had reduced to 5,916 nuclear warheads on 1,188 strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. |3| Under the terms of the 2002 Strategic Offensive Reduction Treaty (known as the Moscow Treaty) between the United States and Russia, this number was to decline to no more than 2,200 operationally deployed strategic nuclear warheads by the end of 2012. The State Department reported that the United States has already reached that level, with only 1,968 operationally deployed strategic warheads in December 2009. |4| The New START Treaty, signed by President Obama and President Medvedev on April 8, 2010, reduces those forces further, to no more than 1,550 warheads on deployed launchers and heavy bombers. |5| According to the October 1, 2016, data exchange under that treaty, the United States now has 1,367 warheads on 681 deployed ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers. |6|

Although these numbers do not count the same categories of nuclear weapons, they indicate that the number of deployed warheads on U.S. strategic nuclear forces has declined significantly in the two decades following the end of the Cold War. Yet, nuclear weapons continue to play a key role in U.S. national security strategy, and the United States does not, at this time, plan to either eliminate its nuclear weapons or abandon the strategy of nuclear deterrence that has served as a core concept in U.S. national security strategy for more than 60 years. In a speech in Prague on April 5, 2009, President Obama highlighted "America's commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons." But he recognized that this goal would not be reached quickly, and probably not in his lifetime. |7| And, even though the President pledged to reduce the roles and numbers of U.S. nuclear forces, the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review noted that "the fundamental role of U.S. nuclear weapons, which will continue as long as nuclear weapons exist, is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners." |8| Moreover, in the 2010 NPR and in the June 2013 Report on the Nuclear Employment Guidance of the United States, |9| the Administration indicated that the United States will pursue programs that will allow it to modernize and adjust its strategic forces so that they remain capable in coming years. The Trump Administration has also indicated continuing support for the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Its guidelines for a new nuclear posture review state that the Secretary of Defense "shall initiate a new Nuclear Posture Review to ensure that the United States nuclear deterrent is modern, robust, flexible, resilient, ready, and appropriately tailored to deter 21st-century threats and reassure our allies." |10|

This report reviews the ongoing programs that will affect the expected size and shape of the U.S. strategic nuclear force structure. It begins with an overview of this force structure during the Cold War, and summarizes the reductions and changes that have occurred since 1991. It then offers details about each category of delivery vehicle–land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers–focusing on their current deployments and ongoing and planned modernization programs. The report concludes with a discussion of issues related to decisions about the future size and shape of the U.S. strategic nuclear force.

Background: The Strategic Triad

Force Structure and Size During the Cold War

Since the early 1960s the United States has maintained a "triad" of strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. The United States first developed these three types of nuclear delivery vehicles, in large part, because each of the military services wanted to play a role in the U.S. nuclear arsenal. However, during the 1960s and 1970s, analysts developed a more reasoned rationale for the nuclear "triad." They argued that these different basing modes had complementary strengths and weaknesses. They would enhance deterrence and discourage a Soviet first strike because they complicated Soviet attack planning and ensured the survivability of a significant portion of the U.S. force in the event of a Soviet first strike. |11| The different characteristics might also strengthen the credibility of U.S. targeting strategy. For example, ICBMs eventually had the accuracy and prompt responsiveness needed to attack hardened targets such as Soviet command posts and ICBM silos, SLBMs had the survivability needed to complicate Soviet efforts to launch a disarming first strike and to retaliate if such an attack were attempted, |12| and heavy bombers could be dispersed quickly and launched to enhance their survivability, and they could be recalled to their bases if a crisis did not escalate into conflict.

According to unclassified estimates, the number of delivery vehicles (ICBMs, SLBMs, and nuclear-capable bombers) in the U.S. force structure grew steadily through the mid-1960s, with the greatest number of delivery vehicles, 2,268, deployed in 1967. |13| The number then held relatively steady through 1990, at between 1,875 and 2,200 ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers. The number of warheads carried on these delivery vehicles increased sharply through 1975, then, after a brief pause, again rose sharply in the early 1980s, peaking at around 13,600 warheads in 1987. Figure 1 displays the increases in delivery vehicles and warheads between 1960, when the United States first began to deploy ICBMs, and 1990, the year before the United States and Soviet Union signed the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START).

Figure 1. U.S. Strategic Nuclear Weapons: 1960-1990

Source: Natural Resources Defense Council, Archive of Nuclear Data.

The sharp increase in warheads in the early 1970s reflects the deployment of ICBMs and SLBMs with multiple warheads, known as MIRVs (multiple independent reentry vehicles). In particular, the United States began to deploy the Minuteman III ICBM, with 3 warheads on each missile, in 1970, and the Poseidon SLBM, which could carry 10 warheads on each missile, in 1971. |14| The increase in warheads in the mid-1980s reflects the deployment of the Peacekeeper (MX) ICBM, which carried 10 warheads on each missile.

In 1990, before it concluded the START Treaty with the Soviet Union, the United States deployed a total of around 12,304 warheads on its ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers. The ICBM force consisted of single-warhead Minuteman II missiles, 3-warhead Minuteman III missiles, and 10-warhead Peacekeeper (MX) missiles, for a total force of 2,450 warheads on 1,000 missiles. The submarine force included Poseidon submarines with Poseidon C-3 and Trident I (C-4) missiles, and the Ohio-class Trident submarines with Trident I, and some Trident II (D-5) missiles. The total force consisted of 5,216 warheads on around 600 missiles. |15| The bomber force centered on 94 B-52H bombers and 96 B-1 bombers, along with many of the older B-52G bombers and 2 of the new (at the time) B-2 bombers. This force of 260 bombers could carry over 4,648 weapons.

Force Structure and Size After the Cold War

During the 1990s, the United States reduced the numbers and types of weapons in its strategic nuclear arsenal, both as a part of its modernization process and in response to the limits in the 1991 START Treaty. The United States continued to maintain a triad of strategic nuclear forces, however, with warheads deployed on ICBMs, SLBMs, and bombers. According to the Department of Defense, this mix of forces not only offered the United States a range of capabilities and flexibility in nuclear planning and complicated an adversary's attack planning, but also hedged against unexpected problems in any single delivery system. This latter issue became more of a concern in this time period, as the United States retired many of the different types of warheads and missiles that it had deployed over the years, reducing the redundancy in its force.

The 1991 START Treaty limited the United States to a maximum of 6,000 total warheads, and 4,900 warheads on ballistic missiles, deployed on up to 1,600 strategic offensive delivery vehicles. However, the treaty did not count the actual number of warheads deployed on each type of ballistic missile or bomber. Instead, it used "counting rules" to determine how many warheads would count against the treaty's limits. For ICBMs and SLBMs, this number usually equaled the actual number of warheads deployed on the missile. Bombers, however, used a different system. Bombers that were not equipped to carry air-launched cruise missiles (the B-1 and B-2 bombers) counted as one warhead; bombers equipped to carry air-launched cruise missiles (B-52 bombers) could carry 20 missiles, but would only count as 10 warheads against the treaty limits. These rules have led to differing estimates of the numbers of warheads on U.S. strategic nuclear forces during the 1990s; some estimates count only those warheads that count against the treaty while others count all the warheads that could be carried by the deployed delivery systems.

According to the data from the Natural Resources Defense Council, the United States reduced its nuclear weapons from 9,300 warheads on 1,239 delivery vehicles in 1991 to 6,196 warheads on 1,064 delivery vehicles when it completed the implementation of START in 2001. By 2009, the United States had reduced its forces to approximately 2,200 warheads on around 850 delivery vehicles. According to the State Department, as of December 2009, the United States had 1,968 operationally deployed warheads on its strategic offensive nuclear forces. |16| NRDC estimated that these numbers held steady in 2010, prior to New START's entry into force, then began to decline again, falling to around 1,900 warheads on around 850 delivery vehicles by early 2015, as the United States began to implement New START (this total includes weapons that the State Department does not count in the New START force). |17| These numbers appear in Figure 2.

Figure 2. U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: 1991-2016

Source: Natural Resources Defense Council, Archive of Nuclear Data, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, Nuclear Notebook.

During the 1990s, the United States continued to add to its Trident fleet, reaching a total of 18 submarines. It retired all of its remaining Poseidon submarines and all of the single-warhead Minuteman II missiles. It continued to deploy B-2 bombers, reaching a total of 21, and removed some of the older B-52G bombers from the nuclear fleet. Consequently, in 2001, its warheads were deployed on 18 Trident submarines with 24 missiles on each submarine and 6 or 8 warheads on each missile; 500 Minuteman III ICBMs, with up to 3 warheads on each missile; 50 Peacekeeper (MX) missiles, with 10 warheads on each missile; 94 B-52H bombers, with up to 20 cruise missiles on each bomber; and 21 B-2 bombers with up to 16 bombs on each aircraft.

The United States and Russia signed a second START Treaty in early 1993. Under this treaty, the United States would have had to reduce its strategic offensive nuclear weapons to between 3,000 and 3,500 accountable warheads. In 1994, the Department of Defense decided that, to meet this limit, it would deploy a force of 500 Minuteman III ICBMs with 1 warhead on each missile, 14 Trident submarines with 24 missiles on each submarine and 5 warheads on each missile, 76 B-52 bombers, and 21 B-2 bombers. The Air Force was to eliminate 50 Peacekeeper ICBMs and reorient the B-1 bombers to non-nuclear missions; the Navy would retire 4 Trident submarines (it later decided to convert these submarines to carry conventional weapons).

The START II Treaty never entered into force, and Congress prevented the Clinton Administration from reducing U.S. forces unilaterally to START II limits. Nevertheless, the Navy and Air Force continued to plan for the forces described above, and eventually implemented those changes. Table 1 displays the forces the United States had deployed in 2001, after completing the START I reductions. It also includes those that it would have deployed under START II, in accordance with the 1994 decisions.

Table 1. U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces Under START I and START II

System Deployed under START I (2001) Planned for START II Launchers Accountable Warheadsª Launchers Accountable Warheads Minuteman III ICBMs 500 1,200 500 500 Peacekeeper ICBMs 50 500 0 0 Trident I Missiles 168 1,008 0 0 Trident II Missiles 264 2,112 336 1,680 B-52 H Bombers (ALCM) 97 970 76 940 B-52 H Bombers (non-ALCM) 47 47 0 0 B-1 Bombersb 90 90 0 0 B-2 Bombers 20 20 21 336 Total 1,237 5,948 933 3,456 Source: U.S. State Department and CRS estimates.

a. Under START I, bombers that are not equipped to carry ALCMs count as one warhead, even if they can carry up 16 nuclear bombs; bombers that are equipped to carry ALCMs count as 10 warheads, even if they can carry up to 20 ALCMs.

b. Although they still counted under START I, B-1 bombers are no longer equipped for nuclear missions.The George W. Bush Administration stated in late 2001 that the United States would reduce its strategic nuclear forces to 1,700-2,200 "operationally deployed warheads" over the next decade. |18| This goal was codified in the 2002 Moscow Treaty. According to the Bush Administration, operationally deployed warheads were those deployed on missiles and stored near bombers on a day-to-day basis. They are the warheads that would be available immediately, or in a matter of days, to meet "immediate and unexpected contingencies." |19| The Administration also indicated that the United States would retain a triad of ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers for the foreseeable future. It did not, however, offer a rationale for this traditional "triad," although the points raised in the past about the differing and complementary capabilities of the systems probably still pertain. Admiral James Ellis, the former Commander of the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM), highlighted this when he noted in a 2005 interview that the ICBM force provides responsiveness, the SLBM force provides survivability, and bombers provide flexibility and recall capability. |20|

The Bush Administration did not specify how it would reduce the U.S. arsenal from around 6,000 warheads to the lower level of 2,200 operationally deployed warheads, although it did identify some force structure changes that would account for part of the reductions. Specifically, after Congress removed its restrictions, |21| the United States eliminated the 50 Peacekeeper ICBMs, reducing by 500 the total number of operationally deployed ICBM warheads. It also continued with plans to remove four Trident submarines from service, and converted those ships to carry non-nuclear guided missiles. These submarines would have counted as 476 warheads under the START Treaty's rules. These changes reduced U.S. forces to around 5,000 warheads on 950 delivery vehicles in 2006; this reduction appears in Figure 2. The Bush Administration also noted that two of the Trident submarines remaining in the fleet would be in overhaul at any given time. The warheads that could be carried on those submarines would not count against the Moscow Treaty limits because they would not be "operationally deployed." This would further reduce the U.S. deployed force by 200 to 400 warheads.

The Bush Administration, through the 2005 Strategic Capabilities Assessment and 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review, announced additional changes in U.S. ICBMs, SLBMs, and bomber forces; these included the elimination of 50 Minuteman III missiles and several hundred air-launched cruise missiles. (These are discussed in more detail below.) These changes appeared to be sufficient to reduce the number of operationally deployed warheads enough to meet the treaty limit of 2,200 warheads, as the United States announced, in mid-2009, that it had met this limit. Reaching this level, however, also depends on the number of warheads carried by each of the remaining Trident and Minuteman missiles. |22|

Current and Future Force Structure and Size

The Obama Administration indicated in the 2010 NPR that the United States will retain a triad of ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers as the United States reduces its forces to the limits in the 2010 New START Treaty. The NPR indicated that the unique characteristics of each leg of the triad were important to the goal of maintaining strategic stability at reduced numbers of warheads:

Each leg of the Triad has advantages that warrant retaining all three legs at this stage of reductions. Strategic nuclear submarines (SSBNs) and the SLBMs they carry represent the most survivable leg of the U.S. nuclear Triad.... Single-warhead ICBMs contribute to stability, and like SLBMs are not vulnerable to air defenses. Unlike ICBMs and SLBMs, bombers can be visibly deployed forward, as a signal in crisis to strengthen deterrence of potential adversaries and assurance of allies and partners. |23|

Moreover, the NPR noted that "retaining sufficient force structure in each leg to allow the ability to hedge effectively by shifting weight from one Triad leg to another if necessary due to unexpected technological problems or operational vulnerabilities." |24|

The Administration continues to support the triad, even as reduces U.S. nuclear forces under New START and considers whether to reduce U.S. nuclear forces further in the coming years. In April 2013, Madelyn Creedon, then the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Global Security Affairs, stated, "The 2010 nuclear posture review concluded that the United States will maintain a triad of ICBMs, SLBMs, and nuclear capable heavy bombers. And the president's F.Y. ' 14 budget request supports modernization of these nuclear forces." |25| Further, in its report on the Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States, released in June 2013, DOD states that the United States will maintain a nuclear triad, because this is the best way to "maintain strategic stability at reasonable cost, while hedging against potential technical problems or vulnerabilities." |26|

On April 8, 2014, the Obama Administration released a report detailing the force structure that the United States would deploy under New START. |27| It indicated that, although the reductions would be complete by the treaty deadline of February 5, 2018, most of the reductions would come late in the treaty implementation period so that the plans could change, if necessary. Table 2 displays this force structure and compares it with estimates of U.S. operational strategic nuclear forces in 2010. This force structure is consistent with the statements and adjustments the Administration has made about deploying all Minuteman III missiles with a single warhead, retaining Trident submarines deployed in two oceans, and converting some number of heavy bombers to conventional-only missions.

Table 2. U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces under New START

(Estimated Current Forces and Potential New START Forces)

Estimated Forces, 2010 Planned Forces Under New START, 2018ª Launchers Warheads Total Launchers Deployed Launchers Warheads Minuteman III 450 500 454 400 400 Trident 336 1,152 280 240 1,090 B-52 76 300 46 42 42 B-2 18 200 20 18 18 Total 880 2,152 800 700 1,550 Source: U.S. Department of Defense, Report on Plan to Implement the Nuclear Force Reductions, Limitations, and Verification, Washington, DC, April 8, 2014.

a. Under this force the United States will retain 14 Trident submarines with 2 in overhaul. In accordance with the terms of New START, the United States will eliminate 4 launchers on each submarine, so that each counts as only 20 launchers. The United States will also retain all 450 Minuteman III launchers, although only 400 would hold deployed missiles.Strategic Nuclear Delivery Vehicles: Recent Reductions and Current Modernization Programs

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs)

In the late 1980s, the United States deployed 50 Peacekeeper ICBMs, each with 10 warheads, at silos that had held Minuteman missiles at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming. The 1993 START II Treaty would have banned multiple warhead ICBMs, so the United States would have had to eliminate these missiles while implementing the treaty. Therefore, the Pentagon began planning for their elimination, and the Air Force added funds to its budget for this purpose in 1994. However, beginning in FY1998, Congress prohibited the Clinton Administration from spending any money on the deactivation or retirement of these missiles until START II entered into force. The Bush Administration requested $14 million in FY2002 to begin the missiles' retirement; Congress lifted the restriction and authorized the funding. The Air Force began to deactivate the missiles in October 2002, and completed the process, having removed all the missiles from their silos, in September 2005. The MK21 reentry vehicles and W87 warheads from these missiles have been placed in storage. As is noted below, the Air Force plans to redeploy some of these warheads and reentry vehicles on Minuteman III missiles, under the Safety Enhanced Reentry Vehicle (SERV) program.

Under the terms of the original, 1991 START Treaty, the United States would have had to eliminate the Peacekeeper missile silos to remove the warheads on the missiles from accountability under the treaty limits. However, the Air Force retained the silos as it deactivated the missiles. Therefore, the warheads that were deployed on the Peacekeeper missiles still counted under START, even though the missiles were no longer operational, until START expired in December 2009. The United States did not, however, count any of these warheads under the limits in the Moscow Treaty. They also will not count under the limits in the New START Treaty, if the United States eliminates the silos. It will not, however, have to blow up or excavate the silos, as it would have had to do under the original START Treaty. The New START Treaty indicates that the parties can use whatever method they choose to eliminate the silos, as long as they demonstrate that the silos can no longer launch missiles. The Air Force filled the silos with gravel to eliminate them, and completed the process in February 2015.

The U.S. Minuteman III ICBMs are located at three Air Force bases–F.E. Warren AFB in Wyoming, Malmstrom AFB in Montana, and Minot AFB in North Dakota. Each base houses 150 missiles.

Force Structure Changes

In the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), the Pentagon indicated that it planned to "reduce the number of deployed Minuteman III ballistic missiles from 500 to 450, beginning in Fiscal Year 2007." |28| The Air Force deactivated the missiles in Malmstrom's 564th Missile Squadron, which was known as the "odd squad." |29| This designation reflected that the launch control facilities for these missiles were built and installed by General Electric, while all other Minuteman launch control facilities were built by Boeing; as a result, these missiles used a different communications and launch control system than all the other Minuteman missiles. According to Air Force Space Command, the drawdown began on July 1, 2007. All of the reentry vehicles were removed from the missiles in early 2008, the missiles were all removed from their silos by the end of July 2008, and the squadron was deactivated by the end of August 2008. |30|

In testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, General Cartwright stated that the Air Force had decided to retire these missiles so that they could serve as test assets for the remaining force. He noted that the Air Force had to "keep a robust test program all the way through the life of the program." |31| With the test assets available before this decision, the test program would begin to run short around 2017 or 2018. The added test assets would support the program through 2025 or longer. This time line, however, raised questions about why the Air Force pressed to begin retiring the missiles in FY2007, 10 years before it would run out of test assets. Some speculated that the elimination of the 50 missiles was intended to reduce the long-term operations and maintenance costs for the fleet, particularly since the 564th Squadron used different ground control technologies and training systems than the remainder of the fleet. This option was not likely, however, to produce budgetary savings in the near term as the added cost of deactivating the missiles could exceed the reductions in operations and maintenance expenses. |32| In addition, to use these missiles as test assets, the Air Force has had to include them in the modernization programs described below. This has further limited the budgetary savings.

When the Air Force decided to retire 50 ICBMs at Malmstrom, it indicated that it would retain the silos and would not destroy or eliminate them. However, with the signing of the New START Treaty in 2010, these silos added to the U.S. total of nondeployed ICBM launchers. The Air Force eliminated them in 2014, by filling them with gravel, so that the United States can comply with the New START limits by 2018.

In a pattern that has become common over the years, Congress questioned the Administration's rationale for the plan to retire 50 Minuteman missiles, indicating that it believed that more Minuteman silos increased U.S. security and strengthened deterrence. In the FY2007 Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 5122, §139), Congress stated that DOD could not spend any money to begin the withdrawal of these missiles from the active force until the Secretary of Defense submitted a report that addressed a number of issues, including (1) a detailed justification for the proposal to reduce the force from 500 to 450 missiles; (2) a detailed analysis of the strategic ramifications of continuing to equip a portion of the force with multiple independent warheads rather than single warheads; (3) an assessment of the test assets and spares required to maintain a force of 500 missiles and a force of 450 missiles through 2030; (4) an assessment of whether halting upgrades to the missiles withdrawn from the deployed force would compromise their ability to serve as test assets; and (5) a description of the plan for extending the life of the Minuteman III missile force beyond FY2030. The Secretary of Defense submitted this report to Congress in late March 2007.

Although the retirement of 50 Minuteman III missiles probably did little to reduce the cost of maintaining and operating the Minuteman fleet, this program did allow both STRATCOM and the Air Force to participate in the effort to transform the Pentagon in response to post-Cold War threats. These missiles may still have a role to play in U.S. national security strategy, but they may not be needed in the numbers that were required when the United States faced the Soviet threat.

During 2012 and 2013, Congress sought to prevent the Administration from initiating an environmental assessment that would advise the possible elimination of up to 50 silos under New START. In addition, the House Armed Services Committee included a provision in its version of the FY2015 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4435, §1634) that would require the Air Force to retain all 450 ICBM silos, regardless of future force structure requirements, budgets, or arms control limits, through 2015. The provision states that "it is in the national security interests of the United States to retain the maximum number of land-based strategic missile silos and their associated infrastructure to ensure that billions of dollars in prior taxpayer investments for such silos and infrastructure are not lost through precipitous actions which may be budget-driven, cyclical, and not in the long-term strategic interests of the United States." It requires that the Secretary of Defense "preserve each intercontinental ballistic missile silo ... in warm status that enables such silo to–(1) remain a fully functioning element of the interconnected and redundant command and control system of the missile field; and (2) be made fully operational with a deployed missile."

The Air Force has continued to conduct flight tests of the Minuteman III missiles, with three live launches and several simulated launches in 2016. It conducted the first flight test of 2017 on February 8. |33| The live launches used missiles pulled from operational wings at Minot Air Force Base and Malmstrom Air Force Base. Each missile delivered a single unarmed warhead to an impact point 4,200 miles (6,759 km) away in the Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. |34|

In the April 2014 report on its planned force structure under New START, the Obama Administration indicated that it planned to retain 400 deployed Minuteman III ICBMs, within a total force of 450 deployed and nondeployed launchers. According to Air Force officials, this option would allow the Air Force to deactivate missiles in silos that have been damaged by water intrusion, repair those silos, and possibly return missiles to them at a later date while it repaired additional silos. If it had eliminated some of the empty silos, it would have had to do so in complete squadrons, regardless of the silos' conditions, and would not have been able to empty and repair the most degraded silos. |35| Congress has also weighed in on this force structure, again arguing that U.S. security would benefit from the retention of more operational ICBM launchers, even if they did not contain operational missiles.

The Air Force has begun to implement this plan, and, according to the data exchanged under the New START Treaty, it had removed 36 missiles from silos by October 2016. |36|

Warhead Plans

Each Minuteman III missile was initially deployed with 3 warheads, for a total of 1,500 warheads across the force. In 2001, to meet the START limit of 6,000 warheads, the United States removed 2 warheads from each of the 150 Minuteman missiles at F.E. Warren AFB, |37| reducing the Minuteman III force to 1,200 total warheads. In the process, the Air Force also removed and destroyed the "bulkhead," the platform on the reentry vehicle, so that, in accordance with START rules, these missiles can no longer carry three warheads.

Under START II, the United States would have had to download all the Minuteman III missiles to one warhead each. Although the Bush Administration initially endorsed the plan to download all Minuteman ICBMs, this plan apparently changed. In an interview with Air Force Magazine in October 2003, General Robert Smolen indicated that the Air Force would maintain the ability to deploy these 500 missiles with up to 800 warheads. |38| Although some analysts interpreted this statement to mean that the Minuteman ICBMs would carry 800 warheads on a day-to-day basis, it seems more likely that this was a reference to the Air Force intent to maintain the ability to reload warheads, and reconstitute the force, if circumstances changed. |39| The 2001 NPR had indicated that the United States would maintain the flexibility to do this. However, in testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, General Cartwright also indicated that some Minuteman missiles might carry more than one warhead. Specifically, when discussing the reduction from 500 to 450 missiles, he said, "this is not a reduction in the number of warheads deployed. They will just merely be re-distributed on the missiles." |40| Major General Deppe confirmed that the Air Force would retain some Minuteman III missiles with more than one warhead when he noted, in a speech in mid-April 2007, that the remaining 450 Minuteman III missiles could be deployed with one, two, or three warheads. |41|

In the 2010 NPR, the Obama Administration indicated that, under the New START Treaty, all of the U.S. Minuteman III missiles will carry only one warhead. It indicated that this configuration would "enhance the stability of the nuclear balance by reducing incentives for either side to strike first." |42| The Air Force completed the downloading process, leaving all Minuteman III missiles with a single warhead, on June 16, 2014. |43|

Unlike under START, the United States did not have to alter the front end of the missile or remove the old bulkhead. As a result, the United States could restore warheads to its ICBM force if the international security environment changed. Moreover, this plan could have changed, if, in an effort to reduce the cost of the ICBM force under New START, the Administration had decided to reduce the number of Minuteman III missiles further in the coming years. Reports indicate that the Pentagon may have reviewed such an option as a part of its NPR implementation study, but, as the report released on April 8, 2014, indicated, it did not decide to pursue this approach. As a result, under New START, each of the 400 deployed Minuteman III missiles will carry a single warhead.

Minuteman Modernization Programs

Over the past 15 years, the Air Force pursued several programs that are designed to improve the accuracy and reliability of the Minuteman fleet and to "support the operational capability of the Minuteman ICBM through 2030." According to some estimates, this effort will likely cost $6 billion-$7 billion. |44| This section describes several of the key programs in this effort.

Propulsion Replacement Program (PRP)

The program began in 1998 and has been replacing the propellant, the solid rocket fuel, in the Minuteman motors to extend the life of the rocket motors. A consortium led by Northrup Grumman poured the new fuel into the first and second stages and remanufactured the third stages of the missiles. According to the Air Force, as of early August, 2007, 325 missiles, or 72% of the fleet, had completed the PRP program; this number increased to around 80% by mid-2008. The Air Force purchased the final 56 booster sets, for a total of 601, with its funding in FY2008. Funding in FY2009 supported the assembly of the remaining boosters. The Air Force completed the PRP program in 2013. |45| In the FY2007 Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 109-364) and the FY2007 Defense Appropriations Act (P.L. 109-289), the 109th Congress indicated that it would not support efforts to end this program early. However, in its budget request for FY2010, the Air Force indicated that FY2009 was the last year for funding for the program, as the program was nearing completion.

Guidance Replacement Program (GRP)

The Guidance Replacement Program has extended the service life of the Minuteman missiles' guidance set, and improved the maintainability and reliability of guidance sets. It replaced aging parts with more modern and reliable technologies, while maintaining the accuracy of the missiles. |46| Flight testing for the new system began in 1998, and, at the time, it exceeded its operational requirements. Production began in 2000, and the Air Force purchased 652 of the new guidance units. Press reports indicate that the system had some problems with accuracy during its testing program. |47| The Air Force eventually identified and corrected the problems in 2002 and 2003. According to the Air Force, 425 Minuteman III missiles were upgraded with the new guidance packages as of early August 2007. The Air Force had been taking delivery of 5 to 7 new guidance units each month, for a total of 652 units. Boeing reported that it had delivered the final guidance set in early February 2009. The Air Force did not request any additional funding for this program in FY2010. However, it did request $1.2 million in FY2011 and $0.6 million in FY2012 to complete the program. It has not requested additional funding in subsequent years.

Propulsion System Rocket Engine Program (PSRE)

According to the Air Force, the Propulsion System Rocket Engine (PSRE) program is designed to rebuild and replace Minuteman post-boost propulsion system components that were produced in the 1970s. The Air Force has been replacing, rather than repairing this system because original replacement parts, materials, and components are no longer available. This program is designed to reduce the life-cycle costs of the Minuteman missiles and maintain their reliability through 2020. The Air Force plans to purchase a total of 574 units for this program. Through FY2009, the Air Force had purchased 441 units, at a cost of $128 million. It requested an additional $26.2 million to purchase another 96 units in FY2010 and $21.5 million to purchase 37 units in FY2011. This would complete the purchase of the units. As a result, the budget for FY2012 does not support the purchase of any additional units, but does include $26.1 million for continuing work installing the units. The FY2013 budget request contained $10.8 million for the same purpose. The Air Force has not requested additional funding in subsequent years.

Rapid Execution and Combat Targeting (REACT) Service Life Extension Program

The REACT targeting system was first installed in Minuteman launch control centers in the mid-1990s. This technology allowed for a significant reduction in the amount of time it would take to retarget the missiles, automated routine functions to reduce the workload for the crews, and replaced obsolete equipment. |48| In 2006, the Air Force began to deploy a modernized version of this system to extend its service life and to update the command and control capability of the launch control centers. This program will allow for more rapid retargeting of ICBMs, a capability identified in the Nuclear Posture Review as essential to the future nuclear force. The Air Force completed this effort in late 2006.

Safety Enhanced Reentry Vehicle (SERV)

As was noted above, under the SERV program, the Air Force plans to deploy MK21/W-87 reentry vehicles removed from Peacekeeper ICBMs on the Minuteman missiles, replacing the older MK12/W62 and MK12A/W78 reentry vehicles. To do this, the Air Force must modify the software, change the mounting on the missile, and change the support equipment. According to Air Force Space Command, the SERV program conducted three flight tests in 2005 and cancelled a fourth test because the first three were so successful. |49| The Air Force installed 20 of the kits for the new reentry vehicles on the Minuteman missiles at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in 2006. The process began at Malmstrom in July 2007 and at Minot in July 2008. As of early August 2007, 47 missiles had been modified. The Air Force purchase an additional 111 modification kits in FY2009, for a total of 570 kits. This was the last year that it planned to request funding for the program. It completed the installation process by 2012.

This program will likely ensure the reliability and effectiveness of the Minuteman III missiles throughout their planned deployments. The W-87 warheads entered the U.S. arsenal in 1986 and were refurbished in 2005. This process extended their service life past 2025. |50|

Solid Rocket Motor Warm Line Program

In the FY2009 Omnibus Appropriations Bill, Congress approved a new program known as the Solid Rocket Motor Warm Line Program. According to Air Force budget documents, this program was intended to "sustain and maintain the unique manufacturing and engineering infrastructure necessary to preserve the Minuteman III solid rocket motor production capability" by providing funding to maintain a low rate of production of motors each year. |51| The program received $42.9 million in FY2010 and produced motors for four Minuteman ICBMs. DOD requested $44.2 million to produce motors for three additional ICBMs in FY2011. The budget request for FY2012 includes an additional $34 million to complete work on the motors purchased in prior years. The FY2013 budget did not contain any additional funding for this program area, although the Air Force continues to support the solid rocket motor production base with work funded through its Dem/Val program (described below).

ICBM Fuze Modernization

According to DOD budget documents, the ICBM fuze modernization program will replace the current MK21 fuze to "meet warfighter requirements and maintain current capability through 2030." This program is needed because the current fuzes have long exceeded their original 10-year life span and the Strategic Command (STRATCOM) does not have enough fuzes available to meet its requirements. According to DOD, the Air force had initially expected to procure around 700 modernized fuzes for the Minuteman fleet. But the new fuzes will also be deployed on the missile that will eventually replace the Minuteman system–the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), which is discussed in more detail below–eventually leading to a much larger program as the Air Force plans to acquire nearly 650 new missiles.

According to the Air Force FY2017 budget request, "the ICBM fuze modernization program will leverage technologies, parts, components, and development/production capabilities resulting from extensive fuze modernization work performed by the U.S. Navy and NNSA" in support of the modernization of a fuze used on submarine-launched ballistic missiles. The Air Force and Navy have been seeking to employ common fuze components, in an effort supported by Congress, to increase efficiency and reduce costs. According to the Air Force, some of the common components include the radar module, the thermal battery assembly, and the path length module. Other fuze components may also use common technologies.

Funding for the fuze modernization program has begun to accelerate. The Air Force received $57.9 million for this program in FY2015 and $142 million in FY2016. It has requested $189.8 million for FY2017. Both the House and Senate included this amount in their versions of the FY2017 Defense Authorization Act; this funding was included in the final bill (P.L. 114-328). The budget documents indicate that funding will continue to exceed $150 million per year through FY2020, with a total program cost of $1.197 billion.

ICBM Dem/Val Program

The Air Force has also funded, through its RDT&E budget, a number of programs under the ICBM Dem/Val (demonstration and validation) title that are expected to allow it to mature technologies that might support both the existing Minuteman fleet and the future ICBM program (known as the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent). Congress appropriated $72.9 million for these programs in FY2014, $30.9 million in FY2015, and $39.8 million in FY2016. DOD has requested an additional $108.7 million for FY2017. The House and Senate both authorized this funding level in their versions of the 2017 Defense Authorization Act. With the FY2017 budget request, the Air Force has moved this program element into the program element for the ground-based strategic deterrent. Hence, although these projects are designed to support both the Minuteman force and the future force, they will likely begin to focus more specifically on the needs of the new missile

The projects funded through the Dem/Val program area include ICBM guidance applications, ICBM propulsion applications, reentry vehicle applications, and command and control applications. In the area of guidance applications, DOD is seeking to "identify, develop, analyze, and evaluate advanced strategic guidance technologies, such as a new solid-state guidance system, for the ICBM fleet." |52| This new system would increase the accuracy of the ICBM force and allow the missiles to destroy hardened targets with a single warhead. However, recent press reports question whether this program is meeting the needs outlined by the Air Force and whether it will produce guidance technologies that can provide the needed increases in ICBM accuracy. |53|

In the area of propulsion applications, DOD is, among other things, "exploring improvements and/or alternatives to current propulsion systems." This program area is specifically seeking to support the solid rocket motor research and development industrial base, so that it will have the capacity to support the ICBM force when the Air Force begins the procurement of its new ground-based strategic deterrent. In the area of reentry vehicle applications, DOD is seeking to both support reentry systems beyond their original design life and develop and test advanced technologies to meet future requirements. The area of command and control applications "evaluates and develops assured, survivable, and secure communications and battlespace awareness." It is focusing on both skills and technologies needed to meet current and future requirements.

Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD)

In 2002, the Air Force began to explore its options for a new missile to replace the Minuteman III, with the intent to begin deploying a new missile in 2018. It reportedly produced a "mission needs statement" at that time, and then began an Analysis of Alternatives (AOA) in 2004. |54| In June 2006, General Frank Klotz indicated that, after completing the AOA, Air Force Space Command had decided to recommend "an evolutionary approach to the replacement of the Minuteman III capability," |55| which would continue to modernize the components of the existing missiles rather than begin from scratch to develop and produce new missiles. He indicated that Space Command supported this approach because it would be less costly than designing a new system "from scratch."

With this plan in place, the Air Force began examining the investments that might be needed to sustain the Minuteman force through 2030. According to General Robert Kehler, then Commander-in-Chief of STRATCOM, the missile should be viable throughout that time. |56| In addition, according to DOD officials, flight tests and surveillance programs should provide the Air Force with "better estimates for component age-out and system end-of-life timelines." |57|

At the same time, the Air Force has begun to consider what a follow-on system to the Minuteman III might look like for the timeframe after 2030. The Air Force began a capabilities-based assessment of its land-based deterrent in early 2011 and began a new Analysis of Alternatives (AOA) for the ICBM force in 2012 with completion expected in mid-2014. |58| According to the Air Force, it requested $2.6 million to begin the study in the FY2012 budget. The FY2013 budget request included $11.7 million for a new project area known as Ground-based Strategic Deterrence (GBSD). According to the Air Force, this effort, which was previously funded under Long-Range Planning, included funding to begin the Analysis of Alternatives (AOA). The FY2014 budget request included $9.4 million to continue this study.

In early January 2013, the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center issued a "Broad Agency Announcement (BAA)" seeking white papers for concepts "that address modernization or replacement of the ground-based leg of the nuclear triad." The papers produced as a part of this study served as an early evaluation of alternatives for the future of the ICBM force, and may have helped select those concepts that will be included in the formal Analysis of Alternatives. According to the BAA, the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center created five possible paths for further analysis. These include one that would continue to use the current Minuteman III baseline until 2075 without seeking to close gaps in the missiles' capabilities, one that would incorporate incremental changes into the current Minuteman III system to close gaps in capabilities, one that would design a new, fixed ICBM system to replace the Minuteman III, one that would design a new mobile ICBM system, and one that would design a new tunnel-based system.

Some analysts have expressed surprise at the possibility that the Air Force would consider deploying a new ICBM on mobile launchers or in tunnels. During the Cold War, the Air Force considered these types of deployment concepts as a way to increase the survivability of the ICBM force when faced with possibility of an attack with hundreds, or thousands, of Soviet warheads. Even during the Cold War, these concepts proved to be very expensive and impractical, and they were dropped from consideration after the demise of the Soviet Union and in the face of deep reductions in the numbers of U.S. and Russian warheads. Some analysts see the Air Force's possible renewed interest in these concepts as a step backward; they argue that the United States should consider retiring its ICBM force, and should not consider new, expensive schemes to increase the missiles' capabilities. Others, however, note that the presence of these concepts in the study does not mean that the Air Force will move in this direction. They note that the 2010 NPR mentioned the possibility of mobile basing for ICBMs as a way to increase warning and decision time, so it should not be a surprise to see requests for further study. However, the cost and complexity of mobile ICBM basing may again eliminate these concepts from further consideration.

According to press reports, this AOA was completed in 2014 and briefed to industry officials in July 2014. The Air Force had reportedly decided to pursue a "hybrid" plan for the next generation ICBM. It would maintain the basic design of the missile, the current communications system, and the existing launch silos, but would replace the rocket motors, guidance sets, post-boost vehicles, and reentry systems. Reports indicated that, although this missile would be deployed in fixed silos, the design would allow the missiles to be deployed on mobile launchers sometime in the future. |59|

However, in recent documents, the Air Force has indicated that the GBSD program "will replace the entire flight system, retaining the silo basing mode while recapitalizing the ground facilities." While this seemed to indicate that there will be a greater level of effort to modernize the silos and launch control facilities, it did not resolve questions about whether the Air Force will continue to retain the option of deploying the missiles on mobile launchers and how much such an option might cost. Nevertheless, there seem to be some indications that the cost of such an option might be prohibitive, and that the priority is on designing a new missile that would be deployed in fixed silos, although mobile launch control facilities remain a possibility.

The Air Force received $75 million for the GBSD program in FY2016 and has requested $113 million for FY2017. The House and Senate both included this level of funding in their versions of the 2017 Defense Authorization Bills; this funding was included in the final bill (P.L. 114-328). DOD budget documents indicate that DOD expects to spend an additional $3.2 billion between FY2018 and FY2021. According to press reports, the Air Force estimated, in 2015, that the program would cost a total of $62.3 billion, in then-year dollars, over 30 years. This includes $48.5 billion for the acquisition of 642 missiles, $6.9 billion for command and control systems, and $6.9 billion to renovate the launch control centers. |60| The 642 missiles would support testing and deployment of a force of 400 missiles.

Recent reports indicate that the Pentagon's Cost Analysis and Program Evaluation Office (CAPE) estimated that the program would cost $85 billion over that time, with $22.6 billion for research and development, $61.5 billion for procurement, and $718 million for related military construction. |61| The Air Force has indicated that the $23 billion difference in estimates is due to the fact that CAPE used different assumptions and a different methodology in its analysis, in part, because the United States has not designed and produced long-range missiles in decades. Normally, DOD would require that the Air Force and CAPE agree on a cost estimate before the program could proceed, but it seems that this will not be the case with the GBSD. Deborah Lee James, the Secretary of the Air Force, has indicated that it could take a year or more to refine cost estimates, based on the submissions received by defense industry as they bid on the program. |62|

According to DOD budget documents, the Air Force is seeking to deliver "an integrated flight system" beginning in FY2028, with booster production beginning in FY2026. Press reports indicate that the system would reach its initial operational capacity, with 9 missiles on alert, by 2029 and would complete the deployment with 400 missiles on alert in 2036. |63| The Air Force, however, plans to install new command and control systems in all 450 existing launch silos by 2037.

While the Air Force appears committed to pursuing the development of a new ground-based strategic deterrent, there is growing recognition among analysts that fiscal constraints may alter this approach. As is noted below, all three legs of the U.S. nuclear triad are currently slated for modernization in the next 10 to 20 years. Each of these programs is likely to stress the budgets and financial capabilities of the services. Nevertheless, the Air Force has sought to allocate more funds to its nuclear missions, both to address personnel and operational issues that have come up in recent years and to pursue its modernization programs. According to the Secretary of the Air Force, Deborah Lee James, the nuclear capabilities of the Air Force are a national asset, so added funding could come not only from the Air Force budget but also from the broader Pentagon budget. |64|

Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles

The U.S. fleet of ballistic missile submarines consists of 14 Trident (Ohio-class) submarines, each equipped to carry 24 Trident missiles. With 2 submarines in overhaul, the operational fleet of 12 submarines currently carries around 1,100 warheads. Under the New START Treaty, each of the submarines will be modified so that they can carry only 20 missiles. The four empty launch tubes will be modified so that they cannot launch missiles; this will remove them from accountability under New START. As a result, the 14 submarines will count as a total of 280 deployed and nondeployed launchers, with 240 deployed launchers counting on the 12 operational submarines. The Navy began the process of reducing the number of launchers on each submarine in FY2015, and plans to complete it before the New START deadline of February 2018. Some estimates indicate that 10 of the submarines had been converted by the end of the 2016. |65|

By the early 1990s, the United States had completed the deployment of 18 Trident ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). Each of these submarines was equipped to carry 24 Trident missiles, and each missile could carry up to 8 warheads (either W-76 warheads or the larger W-88 warheads on the Trident II missile). The Navy initially deployed eight of these submarines at Bangor, WA, and all eight were equipped with the older Trident I missile. It then deployed 10 submarines, all equipped with the Trident II missile, at Kings Bay, GA. During the 1994 Nuclear Posture Review, the Clinton Administration decided that the United States would reduce the size of its Trident fleet to 14 submarines, and that 4 of the older submarines would be "backfit" to carry the Trident II missile.

The Bush Administration's 2001 Nuclear Posture Review endorsed the plan to backfit four of the Trident submarines so that all would carry Trident II missiles. It also indicated that, instead of retiring the remaining four submarines, the Navy would convert them to carry conventional weapons, and designated them "guided missile" submarines (SSGNs). The 2010 NPR also endorsed a force of 14 Trident submarines, although it noted that it might reduce that force to 12 submarines in the latter half of this decade. As was noted above, each submarine will deploy with only 20 missiles to meet the reductions in New START. As a result, the U.S. ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) force may continue to consist of 14 Trident submarines, with 2 in overhaul, through New START implementation.

The SSGN Program

The Navy converted four Trident submarines (the USS Ohio, USS Michigan, USS Florida, and USS Georgia) to carry conventional cruise missiles and other conventional weapons. Reports indicate that the conversion process took approximately $1 billion and two years for each of the four submarines. The SSGNs can each carry 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles, along with up to 100 special forces troops and their mini-submarines. |66|

The first two submarines scheduled for this conversion were removed from the nuclear fleet in early 2003. They were slated to receive their engineering overhaul, then to begin the conversion process in 2004. |67| The first to complete the process, the USS Ohio returned to service as an SSGN in January 2006 |68| and achieved operational status on November 1, 2007. According to the Navy, the Georgia was scheduled for deployment in March 2008, and the other submarines were scheduled to reach that status later in the year. |69| According to Admiral Stephen Johnson, the Director of the Navy's Strategic Submarine Program (SSP), all four of the submarines had returned to service by mid-2008, and two were forward-deployed on routine patrols. According to the Navy, these submarines are likely to remain in service through the mid-2020s.

The Backfit Program

As was noted above, both the 1994 and 2001 Nuclear Posture Reviews confirmed that the Navy would backfit four Trident submarines so that they could carry the newer Trident II (D-5) missile. This process not only allowed the Navy to replace the aging C-4 missiles, it also equipped the fleet with a missile that has improved accuracy and a larger payload. With its greater range, it would allow the submarines to operate in a larger area and cover a greater range of targets. These characteristics were valued when the system was designed and the United States sought to enhance its ability to deter the Soviet Union. The Bush Administration believed that the range, payload, and flexibility of the Trident submarines and D-5 missiles remained relevant in an era when the United States may seek to deter or defeat a wider range of adversaries. The Obama Administration has emphasized that, by providing the United States with a secure second strike capability, these submarines enhance strategic stability.

Four of the eight Trident submarines based in Bangor, WA (USS Alaska, USS Nevada, USS Henry M. Jackson, and USS Alabama) were a part of the backfit program. The Alaska and Nevada both began the process in 2001; the Alaska completed its backfit and rejoined the fleet in March 2002 and the Nevada did the same in August 2002. During the process, the submarines underwent a pre-planned engineered refueling overhaul, which accomplishes a number of maintenance objectives, including refueling of the reactor, repairing and upgrading some equipment, replacing obsolete equipment, repairing or upgrading the ballistic missile systems, and other minor alterations. |70| The submarines also are fit with the Trident II missiles and the operating systems that are unique to these missiles. According to the Navy, both of these efforts came in ahead of schedule and under budget. The Henry M. Jackson and Alabama were completed their engineering overhaul and backfit in FY2006 and reentered the fleet in 2007 and 2008.

The last of the Trident I (C-4) missiles was removed from the fleet in October 2004, when the USS Alabama off-loaded its missiles and began the overhaul and backfit process. All the Trident submarines currently in the U.S. fleet now carry the Trident II missile. |71|

Basing Changes

When the Navy first decided, in the mid-1990s, to maintain a Trident fleet with 14 submarines, it planned to "balance" the fleet by deploying 7 Trident submarines at each of the 2 Trident bases. The Navy would have transferred three submarines from Kings Bay to Bangor, after four of the submarines from Bangor were removed from the ballistic missile fleet, for a balance of seven submarines at each base. However, these plans changed after the Bush Administration's Nuclear Posture Review. The Navy has transferred five submarines to Bangor, "balancing" the fleet by basing nine submarines at Bangor and five submarines at Kings Bay. Because two submarines would be in overhaul at any given time, this basing plan means that seven submarines would be operational at Bangor and five would be operational at Kings Bay.

According to unclassified reports, the Navy began moving Trident submarines from Kings Bay to Bangor in 2002, and transferred the fifth submarine in September 2005. |72| This change in basing pattern apparently reflected changes in the international security environment, with fewer targets within range of submarines operating in the Atlantic, and a greater number of targets within range of submarines operating in the Pacific. In particular, the shift allows the United States to improve its coverage of targets in China and North Korea. |73| Further, as the United States modifies its nuclear targeting objectives it could alter the patrol routes for the submarines operating in both oceans, so that a greater number of emerging targets would be within range of the submarines in a short amount of time.

Warhead Loadings

The Trident II (D-5) missiles can be equipped to carry up to eight warheads each. Under the terms of the original START Treaty, which was in force from 1994 to 2009, the United States could remove warheads from Trident missiles, and reduce the number listed in the database, a process known as downloading, to comply with the treaty's limit of 6,000 warheads. The United States took advantage of this provision, reducing to six warheads per missile on the eight Trident submarines based at Bangor, WA. |74|

During the George W. Bush Administration, the Navy further reduced the number of warheads on the Trident submarines so that the United States could reduce its forces to the 2,200 deployed warheads permitted under the 2002 Moscow Treaty. The United States did not have to reach this limit until 2012, but it had done so by 2009.

The United States may continue to reduce the total numbers of warheads carried on its Trident missiles under the New START Treaty. Unlike START, which attributed the same number of warheads to each missile of a given type, regardless of whether some of the missiles carried fewer warheads, the United States can deploy different numbers of warheads on different missiles, and count only the actual warheads deployed on the force. This will allow each missile to be tailored to meet the mission assigned to that missile. The United States does not need to indicate how many warheads are deployed on each missile at all times; it must simply report the total number of operationally deployed warheads on all of its strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. The parties will, however, have opportunities to confirm that actual number on a specific missile, with random, short-notice inspections. Moreover, the United States will not have to alter the platforms in the missiles, so it could restore warheads to its Trident missiles if circumstances changed.

Modernization Plans and Programs

The Navy initially planned to keep Trident submarines in service for 30 years, but then extended that time period to 42 years. This extension reflects the judgment that ballistic missile submarines would have operated with less demanding missions than attack submarines, and could, therefore, be expected to have a much longer operating life than the expected 30-year life of attack submarines. Therefore, since 1998, the Navy has assumed that each Trident submarine would have an expected operating lifetime of at least 42 years, with two 20-year operating cycles separated by a 2-year refueling overhaul. |75| With this schedule, the submarines will begin to retire from the fleet in 2027. The Navy has also pursued a number of programs to ensure that it has enough missiles to support this extended life for the submarines.

Trident Missile Production and Life Extension

The Navy purchased 437 Trident II (D-5) missiles through FY2008, and planned to purchase an additional 24 missiles per year through FY2012, for a total force of 533 missiles. It continued to produce rocket motors, at a rate of around one per month, and to procure alternation kits (known as SPALTs) needed to meet the extended service life of the submarine. Although the Navy plans to deploy its submarines with only 240 ballistic missiles under New START, it needs the greater number of missiles to support the fleet throughout the their life-cycle. In addition, around 50 of the Trident missiles are available for use by Great Britain in its Trident submarines. The remainder would support the missile's test program throughout the life of the Trident system.

The Navy is also pursuing a life extension program for the Trident II missiles, so that they will remain capable and reliable throughout the 42-year life of the Trident submarines; they will also serve as the initial missile on the new Ohio-replacement submarine. The funding for the Trident II missile supported the purchase of additional solid rocket motors other critical components required to support the missile throughout its service life. Reports indicate the Navy will begin loading the submarines with the new missile in 2017. |76|

The Navy allocated $5.5 billion to the Trident II missile program in FY2008 and FY2009. This funding supported the purchase of an additional 36 Trident II missiles. The Navy spent $1.05 billion on Trident II modifications in FY2010 and requested $1.1 billion in FY2011. In FY2010, $294 million was allocated to the purchase of 24 new missiles, $154.4 million was allocated to missile support costs, and $597.7 million was allocated to the Trident II Life Extension program. In FY2011, the Navy requested $294.9 million for the purchase of 24 new missiles, $156.9 million to missile support costs, and $655.4 million to the Trident II Life Extension Program. The FY2012 budget included $1.3 billion for Trident II missile program. Within this total, $191 million was allocated to the purchase of 24 additional new missiles, $137.8 million was allocated to missile support costs, and $980 million was allocated to the Trident II Life Extension Program. This was the last year during which the Navy sought to purchase new Trident II missiles. The FY2013 budget requested $1.2 billion for the Trident II missile program. This total included $524 million for program production and support costs, and $700.5 million for the Trident II life extension program. The Navy requested $1.14 billion for this program area in FY2014. According to the Navy's budget documents, this allowed it to continue to purchase components, such as the alteration kits for the guidance and missile electronics systems and solid rocket motors for these missiles. The Navy received $1.17 billion for FY2015 and $1.1 billion for FY2016 for Trident II modifications.

The Navy requested an additional $1.1 billion for FY2017. Both the House and the Senate included this funding in their versions of the 2017 Defense Authorization Bill. According to DOD budget documents, this funding supports the "redesign of the guidance system and missile electronics packages" and procures missile electronics, SPALT kits, and other critical components needed to support the missile through the service life of the Ohio submarines. Congress authorized this funding in the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 114-328). The Navy plans to spend $4.8 billion on Trident II modifications between FY2018 and 2021.

W76 Warhead Life Extension

The overwhelming majority of Trident missiles are deployed with the MK4/W76 warhead, which, according to unclassified estimates, has a yield of 100 kilotons. |77| It is currently undergoing a life extension program (LEP) that is designed to enhance its capabilities. According to some reports, the Navy had initially planned to apply this program to around 25% of the W76 warheads, but has increased that plan to cover more than 60% of the stockpile. According to recent estimates, NNSA has delivered more than half of the planned units of the new W76 warheads, and expects to "complete at least 80% of the production units through FY2017." It expects to complete production in 2019. |78| The LEP is intended to add 30 years to the warhead life "by refurbishing the nuclear explosive package, the arming, firing, and fusing system, the gas transfer system, and associated cables, elastomers, valves, pads, cushions, foam supports, telemetries, and other miscellaneous parts." The FY2017 budget request for the Department of Energy includes $222.8 million for the W76 LEP.

Several questions came up during the life extension program. For example, some weapons experts questioned whether the warhead's design is reliable enough to ensure that the warheads will explode at its intended yield. |79| In addition, in June 2006, an inspector general's report from the Department of Energy questioned the management practices at the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which is responsible for the LEP, arguing that management problems had led to delays and created cost overruns in the program. This raised questions about whether NNSA would be able to meet the September 2007 delivery date for the warhead, |80| and, when combined with other technical issues, delayed the delivery of the first W76 warhead until August 2008. The Navy accepted the first refurbished warhead into the stockpile in August 2009. |81|

W88 ALT 370 Program

While most Trident II missiles carry W76 warheads, a portion of the fleet carries the W88 warhead. This warhead, the last to be added to the U.S. nuclear stockpile, entered the force in the late 1980s. According to DOE, this warhead is also in need of work to address concerns with its safety and reliability. In particular, according to recent testimony, the W88 warhead is in the "development engineering phase for Alteration (ALT) 370 to replace the aging arming, fuzing, and firing components." In August 2014, the Nuclear Weapons Council also decided to address potential problems with the warhead's conventional high explosive during the ALT 370 program. This program received $169.5 million in FY2014, $165.4 million in FY2015, and $220.1 million in FY2016. In its FY2016 budget request, NNSA indicated that the additional funding for this program will come from offsets generated by reducing sustainment activities and the quantities of stored warheads for some other types of warheads. In essence, NNSA "identified areas where increased risk could be accepted to produce cost-savings within the current program–without additional funding–and without additional delays to future work." |82| NNSA has requested $281.1 million for the W88 ALT 370 program in FY2017. According to NNSA budget documents, this program is scheduled to produce its first production unit (FPU) in 2020.

The Ohio Replacement Program (ORP) Program

The Navy is currently conducting development and design work on a new class of ballistic missile submarines, originally known as the SSBN(X) program and the Ohio Replacement Program (ORP). The Navy has recently announced that these submarines will be known as the Columbia class; they will replace the Ohio-class Trident submarines as they reach the end of their service lives. |83| The Trident submarines will begin to retire in 2027, and the Navy initially indicated that it would need the new submarines to begin to enter the fleet by 2029, before the number of Trident submarines falls below 12. |84| To do this, the Navy would have had to begin construction of its new submarine by 2019 so that it could begin to enter the fleet in 2029. |85| However, in the FY2013 budget request, the Navy delayed the procurement of the new class of submarines by two years. As a result, the first new submarine will enter the fleet in 2031 and the number of SSBNs in the fleet is expected to decline to 10 for most of the 2030s.

Costs and Funding

The SSBN(X) program received $497.4 million in research and development funding in the Navy's FY2010 budget. The Navy requested an additional $672.3 million in research and development funding for the program in its FY2011 budget proposal. The FY2012 budget included $1.07 billion to develop the SSBN(X). It expected to request $927.8 million in FY2013, with the funding of $29.4 billion between 2011 and 2020. However, with the delay of two years in the procurement of the first SSBN(X), the Navy budgeted only $565 million for the program in FY2013. It then budgeted $1.1 billion for FY2014 and $1.2 billion in FY2015. It received an additional $1.39 billion in FY2016, with $971.4 million allocated to submarine development and $419.3 million allocated to power systems.