| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

19Mar13

Equipo Nizkor

Dismantling the Impunity Model in Argentina

The Adolfo Scilingo Case

Tackling impunity as a social model in bringing perpetrators to justice

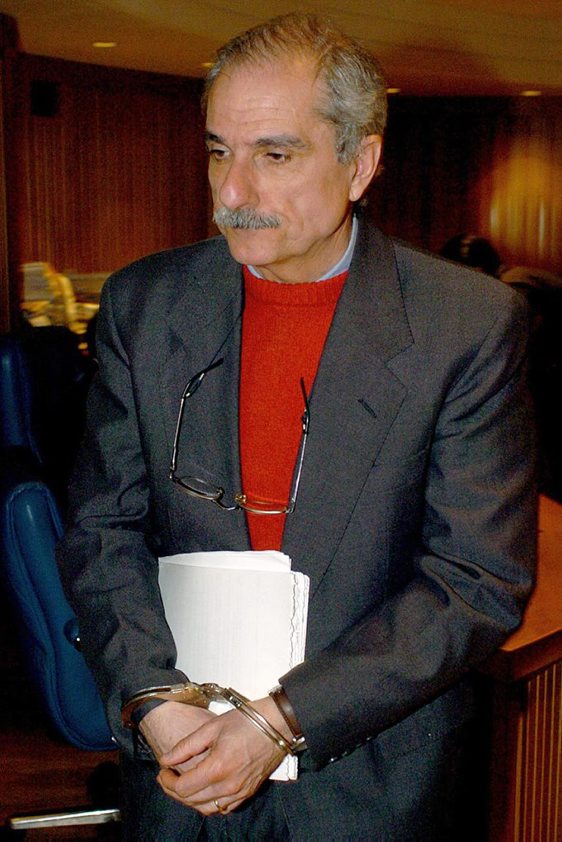

Adolfo Francisco Scilingo after hearing the verdict in Madrid's High Court on 19 April 2005 and holding the text of the judgement. Argentinian Captain Adolfo Francisco Scilingo was sentenced on charges of crimes against humanity during the 1976-1983 Argentine dictatorship. (AFP Doc. Ref. PAR2005041946335)The work of Equipo Nizkor, since its foundation in 1994, has been based on achieving the domestic application of international criminal law and international human rights law to form a framework for the struggle against impunity for cases of gross violations of human rights. It sought to do this by using the international law classification of crimes against humanity in ordinary European jurisdiction.

This objective entailed the implementation of a strategy with reference to the Argentinian and Chilean impunity models so that those responsible for systematic killings or extermination can be brought to justice. The strategy was first tested with the commencement of legal proceedings in Italy and Spain, in 1996, on behalf of the Italian and Spanish who disappeared during the Argentinian dictatorship. To institute these proceedings in Madrid, Equipo Nizkor worked with the Argentinian historic human rights associations.

The fight to bring a domestic legal case for crimes against humanity

More than 10 years' work is reflected in the sentence published in Madrid in April 2005 in the case of Adolfo Scilingo, an Argentinian navy officer. In November 2007, the Spanish Supreme Court confirmed, on appeal, that, that the crimes committed by Adolfo Scilingo are crimes against humanity. Adolfo Scilingo took a direct part in the infamous "death flights".

The origin of the case which led to the arrest and ultimate conviction of Scilingo, and Equipo Nizkor's direct participation in bringing this about, can be traced back to 1996.

On the 15th and 16th February of 1996 at the offices of the European Parliament in Madrid, a conference was held called the "First Conference on Impunity in Latin America". Equipo Nizkor were co-organisers. At that conference, Equipo Nizkor and the historical Argentinian human rights organizations (SERPAJ and the Association of the Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared) studied the case for and decided to prepare litigation for crimes committed against the "Spanish disappeared" in Argentina.

Anticipating the presentation of this lawsuit by Equipo Nizkor and the Argentinian associations, the Progressive Union of Prosecutors (Unión Progresista de Fiscales) submitted an initial complaint on 28th March 1996 (which became known as the "Castresana complaint" after the name of the Prosecutor who signed and submitted it). That complaint was focussed on the crimes committed during the last Argentinian dictatorship. The documents submitted by Carlos Castresana were erroneous (consisting of a list which included errors in both the names of the victims and the perpetrators) and Equipo Nizkor intervened to correct the mistakes and to ensure that the case was not closed with prejudice.

Admiral Emilio Massera (L), Lieutenant General Jorge Rafael Videla (C), President of Argentina amd General Orlando Ramon Agosti (R), Commandant of Argentinian Air Force attend an official ceremony, Argentina, 01 January 1977. After leading the military coup of 24 March 1976, Videla became President as head of three-man military junta including General Agosti and Admiral Massera. (AFP Doc. Ref. ARP1543147)This case, which later became known as the "Argentinian case", was assigned to Central Investigating Court No. 5. and the proceedings were opposed from the outset by the Government of Spain and the Public Prosecutor's office. In the initial stages of the Argentinian case, when the complaint was first submitted, the Office of the Prosecutor tried to close it. To do so, the initial complaints were filed during the interregnum between the outgoing government of Felipe González and the incoming one of José MĒ Aznar.

A plenary session of the Supreme Court chambers' prosecutors (Junta de Fiscales de Sala del Tribunal Supremo) was convened in April 1996 to decide whether or not to accept or reject the case. Only one prosecutor, Jesús Vicente Chamorro, confronted the meeting and asked the outgoing Public Prosecutor whether he did, indeed, plan to dismiss the first criminal complaint brought in respect of crimes committed against Spanish nationals abroad since the period of the Republic.

This question had a strong impact on the Public Prosecutor who decided "that he did not support the case, but was not going to recommend its dismissal". The position of the Prosecutor's Office only changed at the end of Adolfo Scilingo's oral trial.

The Nuremberg legacy makes it possible to attain justice

Shortly thereafter, in December 1996, again with the participation of Equipo Nizkor, an International Conference was held in Santiago, Chile entitled "Impunity and its effects on Democratic Process" (In Spanish). This is still the largest conference to date on impunity and the UN Rapporteur on civil and political rights, Mr. Louis Joinet, revised his final report the "Question of the impunity of perpetrators of human rights violations (civil and political)", to reflect the discussions at the conference, certainly the greatest advance until then in the United Nations system on the issue of impunity

Equipo Nizkor, under its President Gregorio Dionis, then formed an ad hoc working group with the objective of systematizing the development of international criminal law since Nuremberg so that it could be applied in ordinary jurisdictions.

Prior to this, there had been no legal or academic work addressing this issue and the consequence of these efforts was the socialization in systematized form of the Nuremberg legacy and international jurisprudence to date. From its outset, the working group benefited from the contribution of Richard Wilson (Director of the "International Human Rights Law Clinic" at Washington College of Law, American University); later on it was also assisted by contributions from Hastings College of Law, University of California, the law faculty of the University of Yale and other independent experts who had spent time with Equipo Nizkor at its Madrid offices. Equipo Nizkor has carried out the only translation into Spanish of the jurisprudence of Nuremberg. The working group also achieved its systematization for use in domestic courts.

A well defined legal strategy

One of the greatest problems of developing a strategy to achieve a judgement in ordinary jurisdiction for crimes against humanity was that in Spain there is no concept of trial in absentia. This created a serious challenge: how to ensure that a person responsible for such serious crimes is arrested in a European jurisdiction which allows extradition to Madrid, without reliance on the support of any national government and notwithstanding State opposition, primarily in this case, that of Spain, Argentina and Chile.

The ad hoc working group studied the most likely circumstances in which to bring about an arrest, and identified the profile of the type of individual most likely to meet these conditions.

One aspect of the work involved the study and analysis of the jurisprudence and legal process so that the group would be ready to act whenever an official with the right profile was identified as being in a European country. Part of this analysis comprised a review of the judicial co-operation agreements dealing with arrest and extradition that then existed between the following countries: the USA with Europe, Argentina and Chile, and Spain with Italy, Great Britain, France and Germany.

In parallel, the group commenced a strategy in Chile and Argentina to identify potential candidates with the kind of profile that might lead them to surrender themselves to the authorities. These could potentially be military officers or police officers who experienced tensions in their relationship with their peers due to their participation in the crimes perpetrated. In this strategy Equipo Nizkor consulted with experts in psychiatric analysis of war criminals.

These efforts were followed by specific offers being made to several likely individuals to provide testimony in Madrid. At least 8 such offers were made in Argentina but in Chile the work did not progress beyond case analysis.

As a result, Adolfo Scilingo arrived in Madrid on October 6th, 1997 and appeared voluntarily before the National Court on October 7th, 1997 to give testimony for the first time before the Spanish court. Thus, the consequence of this strategy was the trial of Adolfo Scilingo, which to date is still the only case, apart from those in the context of WWII, to result in a conviction for crimes against humanity in ordinary European jurisdiction.

Equipo Nizkor directed the case strategy and carried out the systematization of all the evidence as well as preparing the criminal complaint and subsequent submissions based on the criminal classification of crimes against humanity. During the investigation phase of the case various challenges arose. In addition to the media disinformation campaigns, there were several critical situations during the proceedings, such as the occasion when, because of the official judicial holidays which last the month of August, there was a serious danger that Adolfo Scilingo would be released on bail. This would almost certainly have resulted in him fleeing Spain. The delays in the investigation phase in Central Investigating Court Nē 5 were also a serious problem in that, what are already excessively long time periods during which an individual may be detained in Spain for the purposes of investigation prior to trial, were almost allowed to expire without commencement of the trial.

A judgement for crimes against humanity at last

In fact, the judgement against Adolfo Scilingo was published and notified just before the maximum period for detention had expired and Scilingo would have had to have been released. Incredible as it may seem, several of the accusing parties who had joined as complainants in the proceedings took part in this dangerous situation. During the course of the proceedings itself, Equipo Nizkor had been obliged to intervene to reduce the long list of indirect witnesses in order to curtail the length of the trial and obviate the risk of Scilingo's release. This in no way affected the case against Scilingo given the overwhelming strength of the documentary evidence already submitted.

It was only at the end of the investigation phase, when what is known in Spanish law as the "intermediate phase" commenced, immediately preceding the trial itself, that the complainants were finally allowed access to the complete case documents in the possession of the court (the sumario). The case file comprised 104 volumes of principal exhibits, accessible to all parties, and 183 volumes of what is known as "separate" exhibits , which were not available to the parties until the investigation phase had ended. This was a serious problem as the actual documentary evidence of the extermination plan which existed against political opponents and of the crimes against humanity committed were located in the exhibits which the investigating Judge, Baltasar Garzón, had designated secret (or "separate"). This forced the complainants to conduct an analysis and systematization of all this part in record time.

Equipo Nizkor digitalised the record of the criminal proceedings of "Case 19/97", and photographed in full the principal part of the record comprising 104 volumes. It also photographed a selection of documents from the 183 volumes which made up the Pieza Separada (the separate exhibits) of the proceedings. These photographs were taken following an analysis of the record by a team of experts in international human rights law and war crimes, led by Equipo Nizkor. In total more than 30,000 files were made.

At the beginning of the trial, the lawyers who had been advised by Equipo Nizkor and who until then had maintained that the charges against Adolfo Scilingo should be for crimes against humanity, decided to abandon this position under pressure from others, including other lawyers in the proceedings. Fortunately, the Argentinian Association for Human Rights in Madrid, which was a complainant in the proceedings, supported the legal strategy of Equipo Nizkor, and represented by their lawyer, Antonio Segura, was the only complainant (of the 12 private and "popular" parties in the case) who submitted an indictment accusing Scilingo of crimes against humanity. Thus, this was the only party who actually won the case as the judgement concurred in finding Scilingo guilty of such crimes. Equipo Nizkor prepared this indictment and the documentary evidence supporting the accusation.

On 19th April 2005, the Third Section of the Criminal Division of the National Court, made up of Judges Fernando García Nicolás, President; Jorge Campos Martínez, and José Ricardo de Prada Solaesa, Rapporteur, issued its judgement in the Scilingo case. The judgement represents an important advance in the history of international law in that, for the first time, a domestic court applies principles of international law in a manner which is systematic, rational and, in many ways, uniquely important.

It considers in detail the elements of this kind of crime and enables a precise understanding of its significance and of how this category of crime should be used in internal state jurisdictions; in other words, how crimes against humanity apply in domestic law.

It also sets out a well-developed basis for the application of the principle of individual criminal responsibility in ordinary state jurisdiction which affects those who are responsible for the commission of these crimes.

We believe that it constitutes a precedent in the defence of human rights and of international human rights law and in the struggle against models of impunity and we are therefore very pleased by the outcome

The legacy of the Adolfo Scilingo case

In 2007 that judgement was confirmed by the Supreme Court which marked a major turning point in the fight against impunity.

Equipo Nizkor received invaluable assistance and collaboration in the conduct of these proceedings from the Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic of the University of Yale Law Faculty and the International Human Rights Law Clinic at the American University Washington College of Law.

Additionally, Deborah McCrimmon, lawyer from the firm of DLA Piper and a volunteer with Equipo Nizkor, received an award from the California State Bar Association for her contribution in the Scilingo case. These awards were established to recognise attorneys in California for outstanding provision of pro bono legal services.

As a result of this judgement, in June 2005 the Supreme Court in Argentina declared null and void the so-called "impunity laws" (the Laws of Due Obedience and Full Stop) that impeded the prosecution in that country of those responsible for serious crimes committed during the Argentinian Military Dictatorship. The judgement therefore enabled the reopening of numerous criminal proceedings all over the country, and in some of these Equipo Nizkor currently intervenes directly or by giving legal advice and/or by training local lawyers who are conducting the cases. Since the annulment of the impunity laws following the Scilingo verdict, 368 individuals have been convicted in proceedings for crimes against humanity and 40 have been acquitted.

This result has greatly consolidated the use of the criminal classification of crimes against humanity in ordinary jurisdiction, one of Equipo Nizkor's primary goals over the last 15 years.

For more information please go to: http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/espana/juicioral/

[Source: Equipo Nizkor, Charleroi, 19Mar13]

| This document has been published on 19Mar18 by the Equipo Nizkor and Derechos Human Rights. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. |