| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

23Jun16

World Drug Report 2016

Back to topCONTENTS

1. ILLICIT DRUG MARKETS: SITUATION AND TRENDS

A. Extent of drug use

B. Health impact of drug use

C. Extent of drug supply

D. Market analysis by drug type2. THE WORLD DRUG PROBLEM AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

A. Social development

B. Economic development

C. Environmental sustainability

D. Peaceful, just and inclusive societies

E. PartnershipStatistical tables

Regional groupings

Glossary

The World Drug Report 2016 comes at a decisive moment, just months after Member States, at a special session of the General Assembly, adopted a comprehensive set of operational recommendations on the world drug problem.

The session was only the third in the history of the General Assembly to focus on drugs, and the resulting outcome document, entitled "Our joint commitment to effectively addressing and countering the world drug problem", provides a concrete way forward to take action on shared challenges.

In the outcome document, Member States reaffirmed their commitment to addressing persistent, new and evolving challenges in line with the three international drug control conventions, which were recognized as allowing States parties sufficient flexibility to design and implement national drug policies consistent with the principle of common and shared responsibility.

The operational recommendations contained in the outcome document encompass measures to address demand and supply reduction, as well as to improve access to controlled medicines while preventing their diversion; they cover human rights, youth, children, women and communities and highlight emerging challenges and the need to promote long-term, comprehensive, sustainable, development-oriented and balanced drug control policies and programmes that include alternative development.

The text highlights the importance of drug abuse prevention and treatment; encourages the development, adoption and implementation of alternative or additional measures with regard to conviction or punishment; and promotes proportionate national sentencing policies, practices and guidelines for drug-related offences.

Now the international community must come together to make good on its commitments.

The World Drug Report 2016, which provides a comprehensive overview of major developments in drug markets, trafficking routes and the health impact of drug use, sup-ports comprehensive, balanced and integrated rights-based approaches.

This year's report offers insight into the wide-ranging impact of drugs not only on the health and well-being of individuals, but also on the people around them — families and communities. This can include such harms as HIV, as well as the threat of violence, faced in particular by women and children.

The report also flags the alarming rise in heroin use in some regions. While the challenges posed by new psychoactive substances remain a serious concern, heroin continues to be the drug that kills the most people. This resurgence must be addressed urgently.

The report looks at issues of gender, marginalization, stigmatization, violence and human rights, and considers how counter-narcotics strategies can be sensitive to environmental concerns such as deforestation and pollution. It examines the use of the "dark net" and new technologies for drug trafficking, as well as the potential of illicit drug profits to fund terrorism and violent extremism.

Moreover, the 2016 report's thematic chapter focuses on the interlinkages between drugs and development and the importance of "development-sensitive" drug control policies. This is a topic of particular relevance: as Governments noted in the outcome document, "efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals and to effectively address the world drug problem are complementary and mutually reinforcing".

The research contained in the report can support effective drug and development policies. The evidence is clear: illicit drug cultivation and manufacturing can be eradicated only if policies are aimed at the overall social, economic and environmental development of communities; confronting drug trafficking and its associated violence requires strong, transparent and fair criminal justice institutions and targeted efforts to dismantle transnational organized criminal organizations; prevention and treatment of drug use work if they are based on scientific evidence and are gender-sensitive; and the excessive use of imprisonment for drug-related offences of a minor nature is ineffective in reducing recidivism and overburdens criminal justice systems.

There is clearly much work to be done to tackle the many evolving and emerging challenges posed by drugs. The outcome document and its operational recommendations offer a solid foundation, one built on agreed frameworks, informed by evidence and based on the principle of common and shared responsibility.

This report, as with all of the Office's expertise and on-the-ground experience in addressing the many aspects of the world drug problem, is at the disposal of Member States as they strive to meet this call to action.

Yury Fedotov

Executive Director

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on maps do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. A dotted line represents approximately the line of control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Disputed boundaries (China/India) are represented by cross-hatch owing to the difficulty of showing sufficient detail.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Countries and areas are referred to by the names that were in official use at the time the relevant data were collected.

All references to Kosovo in the present publication should be understood to be in compliance with Security Council resolution 1244 (1999).

Since there is some scientific and legal ambiguity about the distinctions between "drug use", "drug misuse" and "drug abuse", the neutral terms "drug use" and "drug consumption" are used in the present report.

All uses of the word "drug" in this report refer to substances under the control of the international drug control conventions.

All analysis contained in this report is based on the official data submitted by Member States to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime through the annual report questionnaire unless indicated otherwise.

The data on population used in the present report are from: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision.

References to dollars ($) are to United States dollars, unless otherwise stated.

References to tons are to metric tons, unless otherwise stated. R stands for the correlation coefficient, used as measure of the strength of a statistical relationship between two or more variables, ranging from 0 to 1 in case of a positive correlation or from 0 to -1 in case of a negative correlation; R2 stands for the square of the coefficient of correlation.

The following abbreviations have been used in the present report:

ATS amphetamine-type stimulants CICAD Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (Organization of American States) CND Commission on Narcotic Drugs EMCDDA European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Europol European Police Office GDP gross domestic product ha hectares INCB International Narcotics Control Board INCSR International Narcotics Control Strategy Report of the United States State Department INTERPOL International Criminal Police Organization MDMA 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine MSM Men who have sex with men MDPV 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone NIDA National Institute on Drug Abuse (United States) NPS new psychoactive substances OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development PMMA para-methoxymethamphetamine PWID people who inject drugs alpha-PVP alpha-pyrrolidinopentiophenone SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (United States of America) SCORE Sewage Analysis CORe group Europe UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS UNDP United Nations Development Programme UNFDAC United Nations Fund for Drug Abuse Control WCO World Customs Organization WHO World Health Organization

"We reiterate our commitment to strengthen our efforts in addressing and countering emerging and persistent challenges and threats of all aspects of the world drug problem ... and we recommend the following: ... promote, as appropriate, the use and analysis of relevant, reliable and objective data ... to improve the implementation of comprehensive, integrated and balanced national drug control strategies, policies and programmes ... and encourage the sharing of best practices and lessons learned."

Outcome document of the special session of the General Assembly on the world drug problem, entitled "Our joint commitment to effectively addressing and countering the world drug problem"

The World Drug Report 2016 is published in the wake of the landmark moment in global drug policy, the special session of the General Assembly on the world drug problem. Chapter I provides a global overview of the supply of and demand for opiates, cocaine, cannabis, amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) and new psychoactive substances (NPS), as well as their impact on health. It also reviews the scientific evidence on polydrug use, treatment demand for cannabis and developments since the legalization of cannabis for recreational use in some parts of the world. Chapter II focuses on the mechanisms of the interaction between the world drug problem and all aspects of sustainable development through the lens of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Drug use and its health consequences

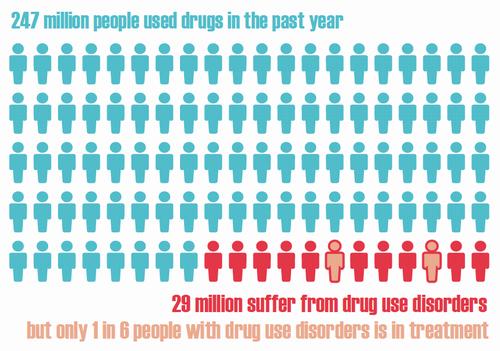

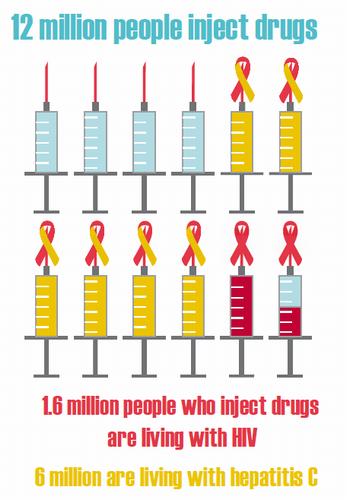

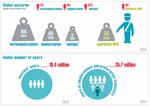

It is estimated that 1 in 20 adults, or a quarter of a billion people between the ages of 15 and 64 years, used at least one drug in 2014. Roughly the equivalent of the combined populations of France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, though a substantial amount, it is one that does not seem to have grown over the past four years in proportion to the global population. Nevertheless, as over 29 million people who use drugs are estimated to suffer from drug use disorders, and of those, 12 million are people who inject drugs (PWID), of whom 14.0 per cent are living with HIV, the impact of drug use in terms of its consequences on health continues to be devastating.

With an estimated 207,400 drug-related deaths in 2014, corresponding to 43.5 deaths per million people aged 15-64, the number of drug-related deaths worldwide has also remained stable, although unacceptable and preventable. Overdose deaths contribute to between roughly a third and a half of all drug-related deaths, which are attributable in most cases to opioids. The time period shortly after release from prison is associated with a substantially increased risk of death from drug-related causes (primarily as a result of drug overdoses), with a mortality rate much higher than from all causes among the general population.

In many countries, prisons remain a high-risk environment for infectious diseases, which is a significant concern for prison health. A number of studies report high levels of drug use in prison, including the use of opiates and injecting drug use. In addition, the prevalence of HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis among persons held in prison can be substantially higher than among the general population. However, despite the high-risk environment and scientific evidence for effective health interventions, there are significant gaps in prevention and treatment services in many prisons around the world.

PWID experience some of the most severe health-related harms associated with unsafe drug use, overall poor health outcomes, including a high risk of non-fatal and fatal overdoses, and a greater chance of premature death. One in seven PWID is living with HIV, and one in two with hepatitis C. PWID are a key at-risk population for HIV and hepatitis, with almost a third of new HIV infections outside sub-Saharan Africa occurring among PWID. Moreover, studies have found people who inject stimulants to engage in more risky sexual behaviours, resulting in a higher risk of HIV infection than for those injecting opiates.

Cannabis remains the most commonly used drug at the global level, with an estimated 183 million people having used the drug in 2014, while amphetamines remain the second most commonly used drug. With an estimated 33 million users, the use of opiates and prescription opioids is less common, but opioids remain major drugs of potential harm and health consequences. The fact that a sharp increase in heroin use has been documented in some markets (particularly North America) where it was previously declining, shows that heroin remains one of the major drugs of public health concern.

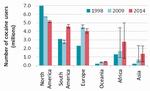

As an overall trend at the global level, the use of cannabis has remained stable over the past three years. In some sub-regions, however, particularly North America and Western and Central Europe, cannabis use has increased. After a period of stability, since 2010 cocaine use has also been rising, mainly because of an increase in cocaine use in South America. On the other hand, the use of amphetamines appears to be stable, but that may underplay the situation in subregions, specifically East and South-East Asia, where recent information on the extent of drug use is unavailable.

Making the global picture of drug use more blurred is the fact that many people who use drugs, both occasionally and regularly, tend to be polydrug users who use more than one substance concurrently or sequentially. For example, the non-medical use of prescription drugs, synthetic stimulants and NPS in lieu of or in combination with more conventional drugs clouds the distinction between users of a particular drug, presenting an interlinked or cyclical epidemic of drug use and related health consequences in recent years.

Treatment related to cannabis use has been increasing in many regions over the past decade. In Europe, an increase in the numbers in treatment for cannabis use has been observed in several countries, despite a decline in the number of frequent (monthly) users. The proportion of people seeking treatment for the first time for cannabis use disorders remains high globally, with nearly half of the people treated for cannabis use disorders being first-time entrants. Changes in patterns of the people in treatment for cannabis use may be attributed to a number of factors, including practices in referrals by the criminal justice system and an expansion in the provision of treatment for cannabis in some countries. While there is some evidence that higher potency cannabis is now more widely available in Europe and the United States, how this might translate into greater harm for cannabis users is not clearly understood.

On average, younger people are seeking treatment for cannabis and amphetamines use disorders more than for other drugs. This reflects the trends in increasing use of cannabis and amphetamines and the resulting increase in people seeking treatment for disorders related to the use of can-nabis and amphetamines. People in treatment for opioid-or cocaine-related disorders are typically in their thirties, and, in many subregions, this reflects an ageing cohort of users in treatment and an overall decrease in the proportion of treatment demand.

Overall, men are three times more likely than women to use cannabis, cocaine or amphetamines, whereas women are more likely than men to engage in the non-medical use of opioids and tranquilizers. Gender disparities in drug use are more attributable to opportunities to use drugs in a social environment than to either gender being more or less susceptible or vulnerable to the use of drugs. Moreover, while in most surveys the prevalence of drug use among young people is reportedly higher than among adults, the gender divide in drug use is narrower among young people than among adults.

DRUG SUPPLY AND MARKETS

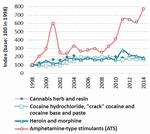

Trends in the quantities of drugs seized worldwide, 1998-2014

Click to enlargeSource: Responses to the annual report questionnaire

The most widely cultivated drug crop continues to be cannabis, which was reported by 129 countries over the period 2009-2014, far more than the 49 countries that reported opium poppy cultivation (mostly located in Asia and the Americas) and the 7 countries that reported coca cultivation (located in the Americas). Leaving aside the disparity in their respective numbers of cultivating countries, opium poppy cultivation has been decreasing in the past year while coca cultivation has been rising.

Cannabis also continues to be the most trafficked drug worldwide, while there has been a large increase in seizures of synthetic drugs. Although there were 234 substances under international control in 2014 (244 in January 2016), the bulk of trafficking (based on reported drug seizures, which reflect both law enforcement activity and drug flows) was concentrated on a far smaller number of substances. Cannabis in its various forms was intercepted in 95 per cent of reporting countries in 2014 and accounted for over half of the 2.2 million drug seizure cases reported to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) that year, followed by ATS, opioids and coca-related substances.

In all countries, more men (90 per cent of the total, on average) than women are brought into formal contact with the criminal justice system for trafficking in drugs or for possession of drugs for personal use. However, the reporting of gender-disaggregated data has improved over the years and shows an increased number of women arrested for drug-related offences in absolute terms. Nevertheless, the proportion of women in drug-related arrests, while fluctuating, showed a downward trend over the 1998-2014 period, particularly for drug trafficking-related offences.

Drug supply via the Internet, including via the anonymous online marketplace, the "dark net", may have increased in recent years. This raises concerns in terms of the potential of the "dark net" to attract new populations of users by facilitating access to drugs in both developed and developing countries.

Opiates

Primarily carried out in South-West Asia and, to a lesser extent, in South-East Asia and Latin America, global opium production in 2015 fell by 38 per cent from the previous year to some 4,770 tons, i.e., to the levels of the late 1990s. The decrease was primarily a consequence of a decline in opium production in Afghanistan (a decrease of 48 per cent from the previous year), mainly as a result of poor yields in the country's southern provinces. However, at 183,000 hectares, Afghanistan still accounted for almost two thirds of the global area under illicit opium poppy cultivation, which decreased by 11 per cent from the previous year to around 281,000 hectares.

UNODC estimates indicate that the global number of opiate users (i.e., users of opium, morphine and heroin) has changed little in recent years and that opiates continued to affect some 17 million people in 2014. It seems unlikely that the sharp decline in opium production in 2015 will lead to major shortages in the global heroin market given the high opium production levels of previous years. The build-up or depletion of previous years' opium inventories may be used to offset annual changes in production and maintain the supply of heroin to user markets. It may take a period of sustained decline in opium production for the repercussions to be felt in the heroin market.

Indeed, the global opiate market appears to be stable despite important regional changes. There are indications that heroin use may be undergoing a resurgence in some countries where it was previously declining. Heroin use increased in North America in the past decade, which resulted in an increase in the level of heroin-related deaths. Long-term trends, in contrast, have been stable or declining in Western and Central Europe since the late 1990s. There are early signs, however, of a surge in the heroin market, with an increase in the availability and use of heroin in some markets in Europe, as well as a major increase in the size of individual seizure cases of heroin destined for Europe. Meanwhile, based on trend perceptions reported to UNODC, the use of opioids may have grown in Africa. Overall opiate use in Asia is reported by experts to have remained largely unchanged over the period 1998-2014 whereas opiate use in Oceania has declined.

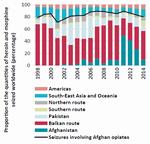

The global interception rate for opiates doubled from the period 1980-1997 (particularly after the special session of the General Assembly on the world drug problem in 1998) to the 2009-2014 period. The largest amount of opiates seized takes place in South-West Asia, followed by Europe. Accounting for 75 per cent of global opium seizures, 61 per cent of global morphine seizures and 17 per cent of global heroin seizures, the largest aggregated opiate seizures worldwide in 2014 were reported by the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The so-called "Balkan route", which supplies Western and Central Europe with Afghan opiates, through Iran (Islamic Republic of) and Turkey via South-Eastern Europe, continues to be the most important conduit for heroin trafficking. However, the so-called "southern route" (through Pakistan or the Islamic Republic of Iran by sea to the Gulf region, Africa (particularly East Africa), South Asia and, to a lesser extent, South-East Asia, the Oceania region and North America), has grown in importance. Meanwhile, opiate trafficking on the so-called "northern route", from Afghanistan to neighbouring States in Central Asia, the Russian Federation and other countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, has started to undergo a resurgence after the decline in the period 2008-2012, while trafficking out of the Golden Triangle is on the increase, mainly due to rising levels of opium production in Myanmar after 2006. Moreover, heroin trafficking in the Americas continues to increase, with heroin and morphine seizures rising from an average of 4 tons over the period 1998-2008 to 7 tons per year over the period 20092014, in line with reported increases in opium production in Latin America over those periods.

Cocaine

Although global coca bush cultivation in 2014 increased by 10 per cent from the previous year, the actual area under coca bush cultivation was the second smallest since the late 1980s. Global cocaine manufacture was slightly higher than in the previous year but still 24-27 per cent lower than the peak in 2007, and thus basically back to the levels reported in the late 1990s. At the same time, there are indications that the increase in global cocaine manufacture observed in 2014 was not a one-off event and may have continued in 2015.

Cocaine trafficking via Africa may be regaining importance, and there are signs of increases in the trafficking of cocaine to Asia, particularly to East and South-East Asia and the Middle East, as cocaine seizures in Asia tripled from an average of 0.45 tons per year over the period 1998-2008 to 1.5 tons per year over the period 20092014. In Oceania, the cocaine market appears to be stabilizing, following rapid growth over the past decade.

Despite these regional fluctuations, the annual prevalence of cocaine use remained largely stable at the global level over the period 1998-2014, fluctuating at between 0.3 and 0.4 per cent of the population aged 15-64. However, as the population has grown, the number of cocaine users has increased, from some 14 million in 1998 to 18.8 million in 2014. Meanwhile, it is likely that there has been a decline in per capita consumption of cocaine, prompted by a decline in the amount of cocaine available for consumption over the period 2007-2014, mainly linked to a drop in cocaine production in the Andean region. In parallel, the number of heavy cocaine users in North America has declined. This points to an overall shrinking of the cocaine market, although the number of (recreational rather than regular) cocaine users in several emerging markets continues to rise.

Cannabis

Despite major changes in some regions, global cannabis consumption has remained somewhat stable in recent years. In 2014, some 3.8 per cent of the global population had used cannabis in the past year, a proportion that has remained stable since 1998. Given the global population growth, this has gone in parallel with an increase in the total number of cannabis users since 1998. The Americas, followed by Africa, remain the main production and consumption regions for cannabis herb, with about three quarters of all cannabis herb seizures worldwide taking place in the Americas in 2014, the largest amounts in North America, while Africa accounted for 14 per cent of all cannabis herb seizures and Europe for 5 per cent. On the other hand, Europe, North Africa and the Near and Middle East remain the principal markets for cannabis resin, the majority of which continues to be produced in Morocco and Afghanistan, as reflected in information provided by Member States on the sources of cannabis resin seized. Accounting for 40 per cent of the total, the largest amounts of cannabis resin seized in 2014 took place once again in Western and Central Europe.

In the United States, although outcome measures such as the burden on the health and criminal justice systems need to continue to be monitored regularly, recent data from the states that have legalized marijuana for recreational use show an increase in cannabis use, as well as in public health and public safety indicators (cannabis-related emergency room visits, hospitalizations, traffic accidents and related deaths), while cannabis-related arrests, court cases and criminal justice system referrals into treatment have declined.

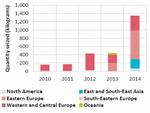

Synthetics: amphetamine-type stimulants and new psychoactive substances

After three years of relative stability, ATS seizures reached a new peak of more than 170 tons in 2014. Since 2009, global amphetamine seizures have fluctuated annually between about 20 and 46 tons, while "ecstasy" seizures more than doubled in 2014, to 9 tons, compared with the annual averages of 4-5 tons since 2009. For the past few years, methamphetamine seizures have accounted for the largest share of global ATS seizures annually, but, although methamphetamine is a feature of ATS markets worldwide, it is particularly dominant in East and South-East Asia and North America. Since 2009, those subregions together have annually accounted for most global methamphetamine seizures. Compared with other subregions, North America has consistently reported the largest amount of methamphetamine seizures each year, whereas between 2009 and 2014, methamphetamine seizures reported in East and South-East Asia almost quadrupled.

In Oceania, strong increases in methamphetamine seizures have been recorded since 2012. There is a growing number of users of crystalline methamphetamine in the region, as well as increased frequency of use among certain user groups, an increase in methamphetamine purity and a decline in purity-adjusted prices, all of which could aggravate the negative impact on the health of individuals and on society in general.

Large amounts of amphetamine tablets labelled with the brand name "Captagon" were reported to have been seized in the Middle East between March 2014 and November 2015. In 2013 and 2014, amphetamine seizures reported in the Middle East were mostly perceived to have originated in Lebanon and the Syrian Arab Republic. Over the same period, some countries reporting amphetamine seizures in the Middle East found that these were intended for trafficking onward to other destinations within the region.

The NPS market continues to be characterized by the large number of new substances being reported. Although data collection for 2015 is still in progress, 75 new substances have been reported to UNODC for the first time, compared with a total of only 66 new substances reported in 2014. Between 2012 and 2014, most substances reported for the first time belonged to the group of synthetic can-nabinoids, but the data reported for 2015 so far show a different pattern: firstly, almost as many synthetic cathi-nones (20) were reported for the first time as were synthetic cannabinoids (21); secondly, a wide range of substances (21) not belonging to any of the major groups identified in previous years were reported for the first time, which included synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl derivatives) and sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines).

Significant quantities of NPS seized have been reported over the past few years. The global market for synthetic NPS continues to be dominated by synthetic cannabinoids (seizures of 32 tons), with North America (specifically the United States with 26.5 tons of seizures) accounting for the largest quantities seized worldwide in 2014, out of the global total of 34 tons (excluding plant-based NPS and ketamine). However, global seizures of synthetic cathi-nones have been steadily increasing since they were first reported in 2010, with seizures tripling to 1.3 tons in 2014 from the previous year.

UNODC monitoring of NPS since 2008 has so far shown a rather dynamic supply situation with elements of persistence (a small number of substances emerge, spread and stay for several years) and change (a considerable number of substances appear for a short time or only locally).

THE WORLD DRUG PROBLEM AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

"We welcome the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and we note that efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals and to effectively address the world drug problem are complementary and mutually reinforcing."

Outcome document of the special session of the General Assembly on the world drug problem, entitled "Our joint commitment to effectively addressing and countering the world drug problem"

The world drug problem is intertwined with all aspects of sustainable development. The analysis of the drug problem, and the response thereto, through the lens of the Sustainable Development Goals reveals the mechanisms of this interaction. All areas of sustainable development, as identified in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, shape the nature and dynamic of the drug problem. At the same time, the impact of the drug problem, and the response thereto, on development can be observed at the individual, community and national levels. In analysing those linkages, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals have been divided into five broad areas: social development, economic development, environmental sustainability, peaceful, just and inclusive societies, and partnership.

Social development

Sustainable Development Goal 10. Reduce inequality within and among countries

The failure to accept or understand that drug dependence is a health condition feeds the cycle of marginalization that often affects people with drug use disorders, making their recovery and social integration more challenging. Furthermore, stigmatizing attitudes towards people who use drugs, which may extend to staff in health-care services, can affect the delivery of effective treatment to those who most need it.

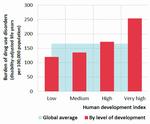

The health impact of drug use increases with development

Click to enlargeSources: Human development index from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); data on burden of disease (disability-adjusted life years) are from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, GBD Compare, 2015. Available from http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare.

Health

Sustainable Development Goal 3. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

The Global Burden of Disease Study indicates that opi-oids, cocaine, amphetamines and cannabis together accounted for almost 12 million life years lost due to premature death or disability in 2013, of which more than 8 million were linked to opioid use disorders. One of the risk factors for the negative health impact of drugs stems from their mode of administration. Injecting drug use, in particular, carries a much greater risk of overdose and infection, including the transmission of blood-borne viruses, such as HIV and hepatitis C, than does smoking, swallowing, snorting or inhaling drugs. Drug use may have repercussions on the health of society in general as PWID may become a group through which sexually transmitted diseases are passed on to other subgroups and the general population. Some studies also corroborate the hypothesis that the use of certain stimulants (whether injected or not) may also influence sexual behaviour itself, thereby increasing the likelihood of high-risk behaviour and sexual transmission — a pattern that raises concern particularly in the case of specific at-risk groups such as men who have sex with men.

Among its targets, Sustainable Development Goal 3 explicitly includes strengthening "the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse". Drug policies based on scientific evidence can, through measures such as prevention and treatment, mitigate the negative health impact of drug use. But when policies are not appropriately tuned to the principles of the international drug control conventions, they can undermine the accessibility of controlled drugs for both medical and research purposes. Three quarters of the global population still have little or no access to medicines containing narcotic drugs and have inadequate access to treatment for moderate to severe pain. The importance of the accessibility of essential medicines, which typically include controlled drugs such as morphine, codeine, diazepam and phenobarbital, has been recognized in target 3.b of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The world drug problem and sustainable development: a complex relationship

Women, girls and youth

Drug use undermines the aspect of sustainable development related to gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. There are marked differences between male and female drug users in terms of preferred drugs and drug-related vulnerabilities. Coupled with the fact that users of several drug types are predominantly male, this leads to a danger that the entire continuum of care may fail to cater adequately for the needs of female drug users, who also have a lack of access to such services.

Sustainable Development Goal 5. Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

Women affected by drug dependence and HIV are more vulnerable and more stigmatized than men. They suffer from co-occurring mental health disorders to a greater extent than men, and they are more likely to have been victims of violence and abuse. Women often also bear a heavy burden of violence and deprivation associated with the drug dependence of family members, hindering the achievement of the sustainable development target of eliminating all forms of violence against all women and girls. Female offenders and prisoners, especially those with drug use disorders, face particular hardship as, in many instances, criminal justice systems are not yet equipped for the special needs of women.

Drug use often affects people during their most productive years. When youth become trapped in a cycle of drug use, and even in the drug trade itself, as opposed to being engaged in legitimate employment and educational opportunities, distinct barriers are effectively raised to the development of individuals and communities.

Economic development

Sustainable Development Goal 1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere

The toll taken by the drug problem may vary in size and shape across countries, both developed and developing, but in one way or another it affects all. Vulnerability to drugs, be it in terms of cultivation, production, trafficking or use, exists in countries at all levels of development.

The relationship between economic development and drugs is particularly evident in the case of the illicit cultivation of drug crops. In rural areas, socioeconomic elements such as poverty and a lack of sustainable livelihoods are important risk factors leading farmers to engage in illicit cultivation. They are also manifestations of poor levels of development which, alongside other development issues linked to security and governance, are enabling elements of large-scale illicit cultivation.

Higher socioeconomic groups have a greater propensity to initiate drug use than lower socioeconomic groups, but it is the lower socioeconomic groups that pay the higher price as they are more likely to become drug dependent

Poverty also has strong links with drug use, albeit in a complex and mutually reinforcing manner. Indeed, the brunt of the drug use problem is borne by people who are poor in relation to the societies in which they live, as can be seen in stark terms in the wealthier countries. More broadly, there is a strong association between social and economic disadvantage and drug use disorders. This pattern can also be seen when looking at different reflections of marginalization and social exclusion, such as unemployment and low levels of education.

Beyond development, a multitude of factors, including geographic location, play a role in shaping the drug problem in a given country. Proximity to a drug-producing area or a major drug trafficking route can, for example, explain the above-average rates of opiate use in the Near and Middle East and South-West Asia, and use of cocaine, including "crack" cocaine, in South America and West Africa. A breakdown of national data on people who use drugs, based on income level, shows, however, that "high-income" countries tend to have a higher prevalence of past-year drug use across the drug categories. Drugs that can command a relatively high price, and ultimately higher profits for traffickers, find an easier foothold in countries with relatively higher levels of per capita income. In the case of substances such as cocaine and heroin, the level of economic development contributes to the formation of consumer markets that are large in terms of both number of users and total revenue.

Different levels of socioeconomic well-being within individual countries also have an effect on the type of drugs used. For example, in the United States, the association between drug use and unemployment is much stronger in the case of "crack" cocaine than other types of cocaine.

Drug markets tend to be influenced by local idiosyncrasies in both developed and developing countries, but sizeable markets for certain substances, notably cocaine and synthetic substances, have taken hold in developed countries before subsequently expanding to developing countries. Prime examples are the emergence of "ecstasy" and other hallucinogens in North America and Europe, as well as the ongoing proliferation of the consumption of NPS in Europe, Japan and North America. The relationship between development and the drug problem thus needs to be viewed in dynamic terms.

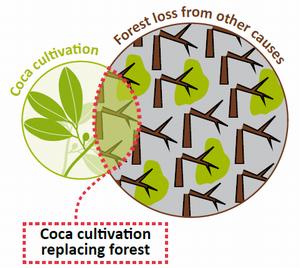

Coca cultivation and deforestation in perspective

Environmental sustainability

Sustainable Development Goal target 15. 5. Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species Illicit crop cultivation often occurs in forested areas and contributes to deforestation when it results in the clearing of woodland. Moreover, illicit crop cultivation frequently takes place in biodiversity hotspots hosting a large number of species with a limited habitat, some of which are protected areas. It tends to occur close to the agricultural frontier, which demarcates the border between pristine forest and developed areas, and can result in the clearing of forests. Although empirical evidence and rigorous analysis do not support the claim that illicit cultivation is the major driver of deforestation, research does suggest that a lack of rural development drives the phenomenon. Analysis has shown, moreover, that drug trafficking can have a direct impact on deforestation through the construction of infrastructure such as landing strips and illegal roads, as well as indirectly through the privatization of public land to create "narco-estates". When eradication induces a displacement of the location of drug crops it may result in deforestation as farmers react to eradication initiatives and seek places out of the reach of law enforcement.

The disposal of chemicals used in the illicit manufacture of cocaine and opiates can also have negative consequences on the environment, contributing to pollution and health hazards in rural communities. In the case of synthetic drugs, the consequences in urban settings not only pose health risks but may also have an impact on the urban and industrial environment.

Peaceful, just and inclusive societies

Violence, rule of law, corruption, illicit financial flows

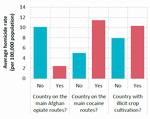

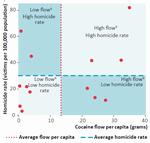

Globally, there is no clear-cut relationship between drug supply and violence

Click to enlargeSource: UNODC Homicide Statistics (2015). Available at www. unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/homicide.html.

Sustainable Development Goal 16. Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels Among the targets associated with Sustainable Development Goal 16, those related to reducing violence, strengthening the rule of law and access to justice, and fighting organized crime, economic crime (corruption and bribery) and illicit financial flows, all have significant links with the world drug problem and the response to it.

The connection between drug trafficking and violence in Latin American countriesa is not an automatic one

Click to enlargeSources: Estimates of the flow of cocaine based on United States, Office of National Drug Control Policy, "Cocaine Smuggling in 2010", January 2012; homicide data from UNODC Homicide Statistics (2016). Available at www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/homicide.html.

a Data were available for 13 countries.

b All flows are expressed per capita.Different stages of the drug problem result in different manifestations of violence. Drug use may lead to violence related to the psychoactive effects of drugs, as well as to crime committed in order to obtain funds for purchasing drugs. The intensity of drug-related violence is greatest, however, when associated with drug trafficking (systemic violence), as the example of Latin America shows. The traumatic effects of violence can also increase vulnerability to drug use.

Yet drug trafficking and production do not necessarily produce violence, as illustrated by the low levels of homicide in transit countries affected by the opiate trafficking routes in Asia. Characteristics of the market and drug trafficking organizations may explain variations: market competition can generate violence in illicit markets, while differences in the internal structure of trafficking networks, which may be characterized by varying degrees of cohe-siveness and hierarchy, can also play a role.

The profits associated with the drug trade are a key motivation for non-State armed groups, including terrorist organizations, to engage in or facilitate drug trafficking. In a number of countries, resources generated in illicit markets such as drug markets have played a role in complicating and extending armed conflicts, often increasing their overall lethality. In general, the drug trade flourishes where State presence is weak, where the rule of law is unevenly applied and where opportunities for corruption exist. At the same time, the wealth and power of drug trafficking organizations provide them with resources to buy protection from law enforcement agents, from politicians and the business sector, thereby reinforcing corruption.

Profit is generated across the entire chain of drug production and distribution, but it is at the final stage that it tends to be highest. A recent UNODC study estimated that almost half of the profit made along the major heroin trafficking route from Afghanistan to Europe was generated in the four largest European consumer markets: France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, the size of the illicit economy associated with drugs, relative to the licit economy, tends to be higher in drug-producing countries, partly because of their relatively smaller economies. This is particularly pronounced in the case of Afghanistan, where, according to UNODC estimates, the total value of the illicit opiate economy was $2.8 billion in 2014 — equivalent to 13 per cent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). The laundering of such illegal proceeds occurs through many different channels, from small, decentralized techniques such as the use of money orders or remittances, to sophisticated uses of front businesses. These forms of illicit financial flows are essential for the survival of criminal groups and constitute a major threat to sustainable development.

Partnership

Sustainable Development Goal 17. Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development Sustainable Development Goal 17 has a strong link with the principles of international cooperation and shared responsibility, embedded in the drug control conventions.

But when analysed together, donor development assistance and donor assistance in drug-related sectors show opposing trends: official development assistance has increased overall, whereas assistance in drug-related sectors has actually decreased significantly since 2008.

How do drug interventions impact sustainable development?

Drug supply and demand reduction efforts

Efforts to eliminate illicit crop cultivation can impact the income source and employment opportunities of farmers and farm labourers. Research has also shown that such efforts have positive development outcomes in the affected communities only if they include development measures to ensure alternative livelihoods and restore security and rule of law. Examples in Colombia and Peru have shown that effective alternative development programmes can weaken the population's ties with armed groups and drug trafficking.

Law enforcement interventions aim to restore the rule of law, the cornerstone of governance and sustainable development, and can also influence the availability of drugs in illicit markets, not only by reducing supply through interdiction but also by increasing the risk for traffickers, which raises the price of drugs in consumer markets. However, enforcement activities by authorities can also generate violence, particularly when they affect the internal and external structure of illegal markets. Research suggests that targeting enforcement and policing on both the protagonists and the elements in the drug trafficking chain that generate the greatest profit and the most violence can be particularly effective in reducing violence. On the other hand, strategies that focus on rapidly disrupting drug trafficking organizations and reducing violence in the short term can sometimes lead to more violence.

Prevention, early intervention treatment, care, recovery, rehabilitation and social integration measures, and the entire continuum of care for people who use drugs, when based on scientific evidence, reduce drug use and thus its impact on public health, which is one of the most important components of the well-being of society. Some of the above measures have also been shown to decrease a range of other risky behaviours such as aggressiveness and truancy. The benefits affect both people who use drugs themselves and society in general, and such efforts have proved effective in preventing, for example, HIV and viral hepatitis.

Drug demand reduction interventions are effective when they rely on evidence-based measures, including those aimed at minimizing the adverse public health and social consequences of drug use, such as appropriate needle and syringe programmes, opiate substitution therapy, antiret-roviral therapy and other relevant interventions that prevent the transmission of HIV, viral hepatitis and other blood-borne diseases associated with drug use. Compulsory confinement in drug treatment centres, on the other hand, often worsens the already problematic lives of people who use drugs and people with drug dependence, particularly the youngest and most vulnerable.

Criminal justice systems and the costs of drug policies

As in the case of law enforcement operations in general, when operations are implemented by impartial, transparent and efficient institutions in compliance with human rights standards, they promote the rule of law and equal justice. But when law enforcement operations go against those principles, incentives may be created for indiscriminate repression and for the violation of citizen rights.

On the basis of limited available data, globally more than three quarters of all those held in prison for drug-related offences have been convicted for drug trafficking and less than a quarter for offences related to personal consumption. There are differences across jurisdictions in terms of definitions, prosecutorial discretion or types and severity of sanctions for drug offences. In some regions, countries exercise more punitive approaches, which may result in incarceration, when dealing with people apprehended for minor drug offences, such as possession of small quantities of drugs for personal consumption. On the other hand, several countries have chosen to limit punishment by adopting alternative measures to incarceration or punishment in minor personal consumption cases without aggravating circumstances (for example, fines, warnings, probation or counselling). The excessive use of imprisonment for drug-related offences of a minor nature is ineffective in reducing recidivism and overburdens criminal justice systems, preventing them from efficiently coping with more serious crime. The provision of evidence-based treatment and care services to drug-using offenders, as an alternative to incarceration, has been shown to substantially increase recovery and reduce recidivism.

Cost of drug policies

Many of the costs arising both directly and indirectly from the drug problem can be quantified in monetary terms. Several economic studies have done so, and their results show that the cost ranged between 0.07 and 1.7 per cent of GDP of the countries studied. Moreover, the majority of countries studied registered a high percentage of overall costs attributable to drug demand and supply reduction interventions (such as prevention, treatment and law enforcement), as opposed to productivity losses and any other indirect costs. It is important to bear in mind that, although those economic studies generally take into account a wide variety of costs, which arise directly and indirectly out of the drug problem, this is usually limited to costs that can be quantified in monetary terms. The non-tangible costs, such as loss of life and impaired quality of life, are frequently not quantified, and when quantified it is usually with reference to a non-monetary metric, such as years of life lost or years lived with a disability. While such studies can be very useful in assessing the economic toll taken on society because of drugs, other considerations also need to come into play when assessing the impact of the world drug problem and in devising policy responses.

Impact of development on the world drug problem

Development can reduce the vulnerability of farmers to engaging in illicit cultivation and production and can bring sustainable reduction in drug cultivation. However, if development interventions are not sensitive to the vulnerabilities of communities to specific drug issues, they may inadvertently trigger dynamics that increase illicit cultivation, as shown by the example of large development programmes in the early 1960s and 1970s in the Andean region.

Initiatives that facilitate trade and ease trade barriers are employed to promote economic development, but globalization may also have ramifications for drug trafficking. By fostering the expansion of trade and global transportation networks, trade openness can also facilitate the cooperation and the formation of alliances among criminal organizations across different countries and, in some cases, reduce the opportunity for law enforcement agencies to monitor international trade.

The geographical spread of the use of certain drugs, such as cocaine and synthetic drugs, is less concentrated today than it was in the past, while Europe, North America and Oceania are increasingly affected by the consumption of NPS. At the same time, rapid economic growth is taking place in large parts of the world where certain drugs are still virtually unknown. It is therefore crucial to bear in mind the potential ramifications of development on drug use, and the experience of developed countries can be enlightening in this regard.

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Development and countering the world drug problem need to work in symbiosis

Many drug policy interventions directly or indirectly result in an improvement in the level of development of their target populations, while operations designed to improve sustainable development often address the vulnerability of people or communities affected by the drug problem and can ultimately help address it. However, as drug and development policies can have an inadvertently counter-productive effect on each other, the two streams of intervention — development and countering the world drug problem — need to work in symbiosis.

In order to be sustainable development-sensitive, efforts to address the world drug problem need:

— To be in line with the requirements of the international human rights instruments.

— To be gender-sensitive, so as to consider the special needs of women and their greater level of stigmatization when designing prevention programmes, treatment interventions for drug dependence, as well as the criminal justice response to drug-related offences.

— To be environmentally friendly, so as to ensure that the curtailment of the illicit supply chain for drugs does not cause deforestation or other environmental damage.

— To ensure that "no one is left behind", by, for example, considering the special needs of men who have sex with men when targeting the spread of infectious diseases among PWID, and the special needs of migrants, including international as well as internal migrants, who can be particularly vulnerable to drug use.

— To overcome the stigmatization of drug users, as this can lead to further marginalization.

— To be based on scientific evidence, so that drug policies can address the core aspects of social development and public health.

At the same time, development interventions should take into account the complex interconnectedness of development and the world drug problem, as well as the potential risks associated with social and economic change. In particular, while continuing to address lack of development in general, policymakers should factor in the specific needs and vulnerabilities of communities affected, so that development efforts do not inadvertently open up space to drug markets.

Success depends on a dual track of development intitiatives.

As the targeting of specific communities affected by the drug problem with a broad sweep of general development strategies may be ineffective, a dual track is needed: maintaining specialized drug interventions in synergy with general developmental investments. This approach has already been embraced in the concept of alternative development and can be expanded to other aspects of the drug problem. Specific drug-related development initiatives need to be mainstreamed into general development initiatives. This can include prevention programmes built into the educational, social welfare and health systems; the strengthening of treatment for drug use and of the provision of care and rehabilitation and reintegration services in the health-care and social welfare systems; training and capacity-building in law enforcement agencies; and raising awareness of the complexity of the drug problem, including the promotion of non-stigmatizing approaches, across all relevant State institutions.

Promotion of an effective human rights-based criminal justice response to the drug problem

Governance and the rule of law represent a crucial area in which the links between the drug problem and development have not been sufficiently recognized. Guaranteeing the rule of law needs to be viewed as a concept wider than mere coercion; it also encompasses inclusive access to justice delivered fairly, in full respect of human rights, through a robust system that places authority in the hands of relevant institutions, with appropriate safeguards.

The first option for people with drug use disorders who are brought into contact with the criminal justice system for minor offences should be an alternative to incarceration. Approaches to tackling minor offences related to drug use disorders through treatment and care as an alternative to imprisonment require effective coordination between the health and justice systems. A set of basic principles to promote the use of non-custodial measures, as well as legal safeguards for persons subject to alternatives to imprisonment, are set forth in the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for Non-custodial Measures (the Tokyo Rules) and in the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the Bangkok Rules).

The right to security also needs to be respected in the implementation of effective drug-control measures. This right requires that State authorities act in compliance with the rule of law and international norms and standards concerning, inter alia, the use of force, the protection of victims and the treatment of offenders. The right to security also implies safety from crime and violence and a corresponding duty of State authorities to prevent and suppress drug trafficking and other related organized-criminal activities that specifically threaten individual citizens.

The dynamics between violence and drug trafficking need to be understood better

The relationship between violence and the production or trafficking of drugs is complex. Violence is not a foregone conclusion of drug trafficking. Factors that determine vio-lence include the level of competition between drug trafficking organizations and how they operate, the sociopolitical conditions of a particular location, levels of corruption and the strength of the underlying rule of law. To avoid the escalation of violence, interventions to elimi-nate drug trafficking have to be sensitive to the circumstances.

Most health consequences of drug use are preventable

Drug use continues to produce negative health consequences, particularly in relation to injecting drug use and drug use disorders. Many of those consequences are preventable and can be avoided through the provision of services such as needle and syringe programmes, overdose prevention, opiate substitution therapy and other evidence-based drug dependence treatment that scientific evidence has proved to be effective. Drug overdose is preventable if substances such as naloxone (a drug that can immediately reverse the effects of opioid overdose) are widely available to people who use opioids.

Drug use and its health consequences should be prevented and treated in prisons

The human rights of people in prisons and other closed settings must continue to be ensured while they are in detention, including their right to health services, particularly for drug dependence treatment and for the prevention and treatment of HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis. A higher risk of death for people with drug use disorders after release from prison points to the need for appropriate interventions such as prison-based opioid substitution therapy, pre-release education on overdose prevention, the availability of naloxone on release from prison, and post-release follow-up.

Heroin still requires the attention of the international community

Drug markets have seen great diversification in the past few years, with the emergence of new substances, new combinations of polydrug use and new injecting behaviours involving stimulants carrying higher risks of infectious diseases. Attention to recent trends should not, however, overshadow the importance of continuing to focus on trends related to a "traditional" drug such as heroin. The resurgence in heroin use, leading to fatal consequences, has been documented in a few countries where it was previously in decline, demonstrating that heroin is not a problem unique to the older generation and that it still needs to be prioritized by the international community. The recent sharp decline in opiate production in Afghanistan should not be overestimated as both the vulnerability, and opportunity, of farmers to cultivating opium poppy have not drastically changed.

Worrying developments in the amphetamine market in the Middle East require closer monitoring

The recent data emerging from the Near and Middle East on "Captagon" (increased seizures, local manufacture and the availability of precursors) show worrying signals for a subregion where drug manufacturing and trafficking have the potential to exacerbate a challenging situation of porous borders, violent conflict, insurgency and limited government control in certain areas. In the past, other regions affected by similar vulnerabilities experienced the development of a drug-violence nexus in which drug manufacture/trafficking and conflict become mutually reinforcing elements. More information, particularly on drug use, is needed in the Near and Middle East to help understand if and how the observed increase in seizures indicates greater drug consumption in the subregion and what the potential implications for drug policy may be.

Greater efforts needed to enhance forensic capacity and monitoring systems for new psychoactive substances

Information on the use of NPS and their health consequences remains limited. Understanding the NPS problem in order to address it more effectively requires efforts on different fronts: supporting countries to improve their forensic capacity relating to NPS detection and to develop or improve monitoring systems that can effectively collect information on the use of NPS and their health consequences. More research is needed to understand the effects on and the risks to users who consume such products, and how to communicate those risks. Also key is understanding the wide range of national legislative responses that have been put in place by Member States in different regions to address the dynamics of the NPS market.

Increased provision of science-based prevention and treatment programmes for cannabis use is needed

Cannabis has been gaining a higher level of visibility at a health-care policy level, in international research and as a result of recent changes in legalization in some parts of the world. An analysis of the numbers in treatment for can-nabis use in the United States and Europe shows an increase over the long term. In Europe, the consistent increase observed in the numbers of people entering treatment for cannabis use is a reflection, in part, of the expansion in the provision of treatment programmes to address the needs of cannabis users, including several programmes targeted at adolescents and young adults. It is important that science-based prevention programmes are available for adolescents and young people so as to prevent the early initiation of cannabis use, and that treatment interventions such as Screen and Brief Intervention (SBI) are available for people who already use cannabis, so as to prevent progression into drug use disorders.

Continual monitoring of new cannabis policies is recommended

Although it is still too early to evaluate the impact of new cannabis policies, the evidence collected to date in the United States points to an increase in cannabis use in states where referendums have led to the legalization of recreational marijuana use. New challenges have emerged in some states of the United States (notably Colorado), including the marketing of unregulated cannabis products (edibles) with a high content of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Moreover, there is evidence of an increasing number of cannabis users driving under the influence, as well as an increase in cannabis-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations. However, cannabis-related arrests and court cases related to cannabis offences have decreased. All of these outcome measures would need to be rigorously monitored and evaluated over a period of time before a final assessment can be made.

Treatment and care: greater focus on polydrug use is a necessity

Polydrug use and the increased complexity of shifts between the use of different drug types pose challenges to people responding to emergencies related to drug use, as well as to those treating drug use disorders. In such instances polydrug use can compromise treatment efforts that are drug specific. Pharmacologically assisted treatment of disorders related to opioid use has proved effective, whereas for other drugs such as stimulants and cannabis, the treatment interventions available are mostly psychosocial and behavioural. This situation requires policymakers and practitioners to be more aware of emerging trends in drug use and to have mechanisms in place to detect and diagnose a wider range of substances used. Furthermore, there is a need to develop guidelines that are science-based for pharmacologically assisted treatment and behavioural therapies for treating people suffering from drug use disorders as a result of multiple drug use.

Legislation, technical assistance and capacity building are key for dealing with the growing importance of the "dark net"

Law enforcement and the criminal justice system in many countries are still not in a position to deal effectively with the anonymous online marketplace known as the "dark net". Apart from practical problems, there are a number of other difficult legal issues that need to be addressed, including: the identification of the responsible jurisdiction, combined with the routine international sharing of information, especially when the physical location of sellers and buyers is unknown; the use of undercover agents (both online and offline) to infiltrate such networks in order to gather evidence and undermine the criminal business model; and the development and implementation of legislation to require suspects to reveal passwords/decryption information when charged with an offence. The provision of technical assistance and capacity-building for Member States to collect and exploit digital evidence is key to addressing the threat posed by drug trafficking via the Internet.

CHAPTER 1

ILLICIT DRUG MARKETS: SITUATION AND TRENDS

Overall drug use remains stable globally

It is estimated that 1 in 20 adults, or a quarter of a billion people aged 15-64 years, used at least one drug in 2014. Although trends in drug use vary across regions, as does updated reporting on data, the extent of drug use among the world population has remained stable over the past four years. Almost 12 per cent of the total number of people who use drugs, or over 29 million people, are estimated to suffer from drug use disorders.

Cannabis remains the world's most widely used drug, with an estimated 183 million people having used the drug in 2014, and amphetamines remain the second most widely used drug. With an estimated 33 million users, the use of opiates and prescription opioids may not be as widespread as the use of cannabis, but opioids remain major drugs of potential harm and health consequences. Where updated data are available, as an overall trend, global use of cannabis has remained stable over the past three years, although in some subregions, particularly North America and Western and Central Europe, cannabis use has increased. In the absence of recent survey data on drug use in Africa, experts in the region also perceive an increase in cannabis use. Moreover, the global trend in cocaine use, which was stable after 2010, has shown a recent trend, mainly as a result of an increase in cocaine use in South America. The global trend in the use of amphetamines is stable, although this may underplay the situation in regions where recent information on the extent of drug use is unavailable. This is particularly the case in Asia, where expert perceptions of trends and treatment admission reports suggest an increase in the use of amphetamines in the region, specifically in East and South-East Asia (see map 1).

The global picture of drug use is compounded by the fact that many people who use drugs, both occasionally and regularly, tend to be polydrug users, |1| |2| meaning that they use more than one substance concurrently or sequentially, usually with the intention of enhancing, potentiating or counteracting the effects of another drug. |3| The non-medical use of prescription drugs, synthetic stimulants and new psychoactive substances (NPS) in lieu of, or in combination with, conventional drugs gives a picture that blurs the distinction between users of a particular drug, presenting an interlinked or cyclical epidemic of drug use and related health consequences in recent years. Additionally, such a pattern of drug use presents challenges to health professionals responding to emergencies related to drug use, as well as to those treating people with disorders related to the use of multiple drugs.

Estimates of the extent of drug use and problem drug use reflect the best information available in 2014 As in previous years, global estimates of the extent of drug use and problem drug use reflect the best available information in 2014, and changes compared with previous years largely reflect information updated by 20 countries, mostly in North America, South America and Western and Central Europe, for which new data on the extent of drug use or problem drug use were made available in 2014. The concept of problem drug use has been used in prior editions of the World Drug Report as a proxy for estimating the number of people with drug use disorders. In 2014, the estimated number of problem drug users increased by 2 million over the previous year, which reflects an increase in the estimated number of opiate users in North America and Western and Central Europe, as well as in the total number of users of cocaine, amphetamines and "ecstasy".

Recent trends in polydrug use and substitution between drugs

Polydrug use encompasses wide variations in patterns of drug use, ranging from occasional alcohol and cannabis use to the daily use of a combination of heroin, cocaine, alcohol and benzodiazepines. |4| |5|

Within polydrug use, the concomitant use of opiates and stimulants such as cocaine and amphetamines is fairly common and has been widely reported. |6| |7| In the past decade, the use of amphetamine and methamphetamine has become quite widespread in different regions, while the number of NPS that are stimulants seems to be constantly increasing. Data on polydrug use are seldom systematically collected, but amphetamines and NPS seem to be reported increasingly in polydrug use patterns in different regions.

Tolerance, cross-tolerance and substitution: managing the effects of drugs

The interplay of individual, biological, cultural, social and environmental factors increases or attenuates the vulnerability of a person to use or to continue using drugs. Continuing to use a drug is considered a conditioned response to the positive reinforcement that the person receives as a result of using the drug. |8| However, in later stages a person continues to use drugs merely to maintain drug dependence, which is characterized by, among other things, the desire and compulsion to use drugs despite evidence of harmful consequences, the development of tolerance — by increasing the quantity of the drug or drugs to achieve the same effects and a state of withdrawal — and the negative consequences experienced when the person stops using the drug or drugs. |9|

Drugs taken together can have a cumulative or synergistic effect, which increases the overall psychoactive experience; that is one way in which drug users may address the development of tolerance. |10| A related phenomenon is "cross-tolerance" — the pharmacological ability of one drug to have generally the same effect on the nervous system as another drug. The phenomenon of cross-tolerance explains in part the frequent substitution of drugs that have a similar effect. Examples of such patterns of drug use include the use of alcohol with benzodiazepines, cannabis or cocaine; concurrent use of heroin, benzodiazepines and antihistamines; the use of alcohol or other opioids (methadone, fentanyl etc.); and the use of cocaine and other stimulants. |11| |12| |13| |14|

In other situations, people who use drugs may offset the negative effects of the drugs by concurrently or sequentially using additional drugs with opposite effects. One such pattern is "speedballing" — when cocaine is injected with heroin or other opioids or when heroin is used with methamphetamine or amphetamine. |15|

Market dynamics: substitution and complementarity of drugs

Market dynamics, reflected by changes in availability, purity or price, can affect the choice of drugs. In such circumstances, people who use drugs can turn to substituting with different drugs; transitioning to alternative routes of drug administration; decreasing their consumption of the drug; or deciding to enter treatment. |16| |17| Common examples are heroin being substituted by oxycodone, desomorphine or other opioids and vice versa, as reported in various regions. |18|

Economic factors and cross-price elasticity may also affect polydrug use. |19| An increase in the price of one drug may result in the use of another (substitution) or it may decrease the use of another, even though its price remains the same (complementarity). For example, a study showed that an increase in the price of heroin resulted in an increase in benzodiazepine and cocaine purchases. |20| In another study, cross-price elasticity analysis showed that in the case of heroin there was significant substitution with prescription opioids and, to a lesser extent, benzodiazepines and methamphetamine. |21| The same study showed that there was limited substitution with other drugs as the price of meth-amphetamine increased.

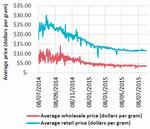

Recent trends in the use of heroin and the non-medical use of prescription opioids in the United States

In the United States of America, over the past decade the non-medical use of prescription opioids and the use of heroin have continued to interplay in the market. Since the high prevalence and associated morbidity and mortality of the non-medical use of prescription opioids have become a major public health issue, |22| a recent increase in heroin use has triggered a sharp increase in heroin-related overdose deaths. |23| |24| Several aspects have driven this change: law enforcement and regulatory actions to address the irrational prescribing and reformulation of prescription opioids with abuse-deterrent technologies; implementation of programmes for monitoring prescription drugs and education of health-care professionals and the public about their appropriate use; |25| and increased accessibility, reduced prices and high purity of heroin in the United States. |26|

In 2014, an estimated 914,000 people aged 12 years or older had used heroin in the past year — a 145 per cent increase since 2007 — while mortality related to heroin use has increased fivefold since 2000. |27| |28| |29| |30|

From the period 2002-2004 to the period 2011-2013, there was an increase in heroin use, particularly among people who also reported the use of other substances. The highest rate of past-year heroin use was among cocaine users (91.5 per 1,000 users), |31| followed by those who reported non-medical use of prescription opioids. Nine out of 10 people who used heroin self-reported co-use of heroin with at least one other drug, and most used heroin with at least three other drugs. |32| Moreover, the proportion of heroin users diagnosed with disorders related to non-medical use of prescription opioids more than doubled, from 20.7 per cent in the period 2002-2004 to 45.2 per cent in the period 2011-2013.

The increase in heroin use in the United States has been more pronounced among a subgroup of people aged 18-25 who report a higher frequency of non-medical use of prescription opioids. |33| Among this group, the likelihood of using heroin in the past year, ever injecting prescription opioids or becoming dependent on heroin increased with the frequency of non-medical use of prescription opioids in the previous year. Those reporting non-medical use of prescription opioids for over 100 days in the past year were nearly eight times more likely to report dependence on heroin than those who reported less frequent non-medical use of prescription opioids.

It appears that the increase in heroin use in the United States had already begun around 2006 and had preceded the changes introduced in policies and practices related to prescription opioids. Nevertheless, given the large number of non-medical users of prescription opioids, even a small proportion who switch to heroin use has translated into a much higher number of people using heroin.

Analysis suggests that the problem of opioid use is not substance-specific and requires holistic approaches to address the interconnected epidemic through prevention of initiation and treatment interventions for people with opioid use disorder. |34|

Shift between injecting heroin, amphetamines and new psychoactive substances in Europe