| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

May15

World Drug Report 2015

Back to topCONTENTS

PREFACE

EXPLANATORY NOTES

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY1. STATUS AND TREND ANALYSIS OF ILLICIT DRUG MARKETS

A. Extent of drug use

B. Health impact of drug use

C. Gender, drug use and health consequences

D. Drug use prevention

E. Treatment of drug use

F. Extent of drug supply

G. Market analysis by drug typeOpiates

H. Conclusions

Cocaine

Cannabis

Synthetic drugs: amphetamine-type stimulants and new psychoactive substancesA. Introduction

B. Setting the scene

C. Analysis of national alternative development strategies

D. Challenging context of alternative development

E. Drivers of illicit cultivation

F. Strategic elements of alternative development programmes

G. Measuring the success of alternative development

H. Points of future interest

I. ConclusionsANNEX I

Tables on drug cultivation, production and eradication and prevalence

UNODC is pleased to present the findings of the World Drug Report 2015, based on the best available data and our longstanding research expertise in the many complex facets of drugs and crime.

Member States are engaged in intensive discussions on the way forward to address the world drug problem, with the General Assembly special session on this topic to take place next year. This report is aimed at providing needed research input and informing collective responses to the challenges posed by the production, trafficking and use of illicit drugs.

The continuing discussions leading to the special session of the General Assembly have recognized the need for drug control policies that are balanced, comprehensive and integrated, with a focus on health and carried out with respect for human rights.

Numerous Security Council and General Assembly resolutions have emphasized the fact that the harm caused by illicit drugs has a significant impact on peace, security and development.

The ongoing debate on the post-2015 development agenda has further underscored the importance of promoting justice and the rule of law, and of addressing the threats that undermine them, including drugs, violence and organized crime.

Risk factors and circumstances that can render people more vulnerable to illicit drugs, as well as facilitate the establishment and expansion of illegal markets, are often related to issues of development, rule of law and governance. Policies can never be pursued in isolation, and drug control is no exception.

The need for such integrated responses, encompassing robust criminal justice action to disrupt organized criminal networks, measures to ensure access to controlled medications for medical purposes, and evidence- and health-based approaches to prevention and treatment, is more evident than ever.

The vulnerability of Africa to drugs and crime remains a grave concern, with increasing seizures of heroin indicating the region's role as a key transit area for global drug trafficking routes. These illicit flows bring with them other forms of organized crime, and undermine security, health and development in an already-fragile region.

The nexus between organized crime and terrorism — in which illicit drug trafficking appears to play a role — poses a serious threat, as emphasized by recent Security Council resolutions calling for redoubled efforts to prevent terrorists from benefiting from transnational organized crime.

Record opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan continues to present formidable challenges for the country and the international community.

Global opium poppy cultivation in 2014 reached its highest level since the late 1930s. The increase in estimated opium and heroin production has not yet been reflected in an increase in heroin supply in most regions. But in some countries there have been signs of increases in heroin-related indicators such as mortality and health emergencies, and in others indications of increased purity and lower prices.

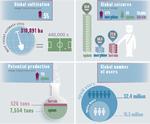

An unacceptable number of drug users worldwide continue to lose their lives prematurely, with an estimated 187,100 drug-related deaths in 2013.

Only one out of six problem drug users globally has access to treatment. Women in particular appear to face barriers to treatment — while one out of three drug users globally is a woman, only one out of five drug users in treatment is a woman.

Clearly more work needs to be done to promote the importance of understanding and addressing drug dependence as a chronic health condition requiring, like HIV/AIDS, long-term, sustained treatment and care.

UNODC remains committed to working with Member States, as well as our United Nations and other partners, to further these efforts.

The thematic chapter of this year's report focuses on alternative development.

Alternative development presents many challenges, with programmes often undertaken in marginalized, isolated areas with limited government control, unclear land rights and lack of infrastructure, where few other development actors may be operating.

Nevertheless, the decades-long experience of UNODC has made it clear that alternative development can work, when initiatives are informed by a long-term vision, sustained with adequate funding and political support, and integrated into a broader development and governance agenda.

Approached holistically, alternative development has the potential to break the vicious cycle trapping poor farmers and to act as a catalyst for viable livelihoods that do not depend on illicit cultivation.

The World Drug Report 2015 chapter on alternative development, based on reviews of successful projects, highlights factors that have contributed to fostering a sustainable licit economy, including transfer of skills and access to land, credit and infrastructure, as well as marketing support and access to markets.

The chapter further underlines the potential of alternative development to contribute to environmental protection, empower women and support communities affected by other forms of crime, including illegal mining or wildlife and forest crime.

Unfortunately, the report also shows that widespread political support for alternative development has not been matched by funding.

Member States have repeatedly endorsed alternative development. There is also a welcome trend towards South-South cooperation, with the exchange of best practices and local experiences, as well as increased financial investments and technical support from countries such as Bolivia (Plurina-tional State of), Colombia, Peru and Thailand.

Nevertheless, overall gross disbursements of alternative development funds from countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development accounted for just 0.1 per cent of global development assistance in 2013.

The post-2015 development agenda and the process towards the special session of the General Assembly on the world drug problem to be held in 2016 can provide an important impetus for alternative development efforts, as well as for broader interventions addressing supply and demand.

Impoverished farmers growing coca and opium poppy to eke out an unsustainable living; fragile regions and communities reeling from the harm caused by the transit of illicit drugs, on their way to richer markets; women, men and children struggling with drug dependence, with nowhere to turn. Illicit drugs hurt so many people, in so many places, and they need our help. The international community must respond with determination and compassion, and I hope the World Drug Report 2015 will help to reinforce this message.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Member States for their help in producing this report, which relies on the willingness to share data, promote transparency and provide assistance. That is to say, it relies on the very spirit of openness and shared responsibility needed to address the multidimensional challenges posed by illicit drugs, and we count on your continued support.

Yury Fedotov

Executive Director

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on maps do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. A dotted line represents approximately the line of control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Disputed boundaries (China/India) are represented by cross-hatch owing to the difficulty of showing sufficient detail.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Countries and areas are referred to by the names that were in official use at the time the relevant data were collected.

All references to Kosovo in the present publication should be understood to be in compliance with Security Council resolution 1244 (1999).

Since there is some scientific and legal ambiguity about the distinctions between "drug use", "drug misuse" and "drug abuse", the neutral terms "drug use" and "drug consumption" are used in the present report.

All analysis contained in this report is based on the official data submitted by member States to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime through the annual report questionnaire unless indicated otherwise.

The data on population used in the present report are from: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision.

References to dollars ($) are to United States dollars, unless otherwise stated.

References to tons are to metric tons, unless otherwise stated.

The following abbreviations have been used in the present report:

ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ATS amphetamine-type stimulants CBD cannabidiol CICAD Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (Organization of American States) DEA Drug Enforcement Administration EMCDDA European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Europol European Police Office FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FWID females who inject drugs GDP gross domestic product GIZ German Agency for International Cooperation INCB International Narcotics Control Board INCSR International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, of the United States State Department LSD lysergic acid diethylamide MDA 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine MDMA 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine MWID males who inject drugs 3,4-MDP-2-P 3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propanone 4-MEC mythylethcathinone NPS new psychoactive substances OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development PWID people who inject drugs SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (United States) THC Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS USAID United States Agency for International Development UNFDAC United Nations Fund for Drug Abuse Control UNDCP United Nations International Drug Control Programme UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime WHO World Health Organization WTO World Trade Organization

The World Drug Report presents a comprehensive annual overview of the latest developments in the world's illicit drug markets by focusing on the production of, trafficking in and consumption of the main illicit drug types and their related health consequences. Chapter 1 of the World Drug Report 2015 provides a global overview of the supply of and demand for opiates, cocaine, cannabis, amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) and new psychoactive substances (NPS), as well as their impact on health, and reviews the scientific evidence on approaches to drug use prevention and addresses general principles for effective responses to treatment for drug use. Chapter 2 focuses on how alternative development, within the broader context of the development agenda, aims to break the vicious cycle of illicit crop cultivation by providing farmers with alternative livelihoods.

Global trends in the estimated number of drug users, 2006-2013

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

Note: Estimated percentage of adults (aged 15-64) who have used drugs in the past year.Global trends in the estimated prevalence of drug use, 2006-2013

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

Note: Estimates are for adults (aged 15-64), based on past-year use.Global trends in the prevalence of use of various drugs, 2009-2013

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

Note: Based on the estimated percentage of adults (aged 15-64) who have used the substance in the past year.According to the most recent data available, there has been little change in the overall global situation regarding the production, use and health consequences of illicit drugs. The health consequences of illicit drug use continue to be a matter of global concern, as the vast majority of problem drug users continue to have no access to treatment. Furthermore, the increase in global opium poppy cultivation and opium production to record levels has yet to have major repercussions on the global market for opiates. This raises concerns about the size of the challenge to law enforcement posed by increasingly sophisticated and versatile organized criminal groups.

Drug use and its health consequences

It is estimated that a total of 246 million people, or 1 out of 20 people between the ages of 15 and 64 years, used an illicit drug in 2013. That represents an increase of 3 million over the previous year but, because of the increase in the global population, illicit drug use has in fact remained stable.

The magnitude of the world drug problem becomes more apparent when considering that more than 1 out of 10 drug users is a problem drug user, suffering from drug use disorders or drug dependence. In other words, some 27 million people, or almost the entire population of a country the size of Malaysia, are problem drug users. Almost half (12.19 million) of those problem drug users inject drugs, and an estimated 1.65 million of those who inject drugs were living with HIV in 2013.

This places a heavy burden on public health systems in terms of the prevention, treatment and care of drug use disorders and their health consequences. Only one out of every six problem drug users in the world has access to treatment, as many countries have a large shortfall in the provision of services. The annual number of drug-related deaths (estimated at 187,100 in 2013) has remained relatively unchanged. An unacceptable number of drug users continue to lose their lives prematurely, often as a result of overdose, even though overdose-related deaths are preventable.

Notwithstanding national and regional variations in trends in drug use, the limited data available indicate that the use of opiates (heroin and opium) has remained stable at the global level. Mainly as a result of trends in the Americas and Europe, cocaine use has declined overall, while the use of cannabis and the non-medical use of pharmaceutical opioids have continued to rise. Trends in ATS use vary from region to region, and some subregions such as South-East Asia have reported an increase in methamphetamine use.

There are also indications that the number of people requiring treatment for cannabis use is increasing in most regions. The evidence suggests that more drug users are suffering from cannabis use disorders, and there is growing evidence that cannabis may be becoming more harmful. This is reflected in the high proportion of persons entering treatment for the first time for cannabis use disorders in Europe, North America and Oceania. According to the limited information available, cannabis ranks first among the drug types for which people in Africa enter treatment for drug use.

Lifetime, annual and past-month prevalence of drug use in prisons (based on 62 studies from 43 countries over the period 2000-2013)

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire; and C. Carpentier, L. Royuela and L. Montanari, "The global epidemiology of drug use in prison" (2015).

Note: Symbols represent median prevalence with vertical lines depicting inter-quartile range. Data on lifetime, annual and past-month use are not consistent across studies (this explains why the annual prevalence of cocaine use has a median value lower than the past-month use).Cannabis is by far the most frequently used drug in prisons. Though data on the subject are limited, there are indications that one third of prisoners have used a drug at least once while incarcerated. Lifetime and recent (past-month) use of heroin in prisons is much higher than that of cocaine, amphetamines or "ecstasy". Prison is a high-risk, controlled environment where drug use, including injecting drug use, often takes place in particularly unsafe conditions. This may explain why the prison environment can be characterized by high levels of infectious diseases, particularly HIV but also hepatitis C and tuberculosis, and by limited access to prevention and treatment, which increases the risk of contracting blood-borne viruses.

The number of people requiring treatment for ATS use is also increasing globally. This is probably attributable to the sheer weight of numbers, as the prevalence of ATS use is relatively high in Asia, where there is high demand for treatment but the expertise in treating ATS use disorders is not at the same level of sophistication as the expertise in treating opiate use disorders.

NPS are marketed as alternatives to internationally controlled drugs and are purported to produce effects similar to those of their "traditional" counterparts. They have the potential to pose serious risks to public health and safety. Information and research on the potential harm caused by NPS are limited, but the proliferation of the estimated 500 NPS, including mephedrone, poses a health threat to drug users and has increased demand for treatment for drug use.

Even though one out of three drug users is a woman, only one out of five drug users in treatment is a woman.

Cocaine remains the primary drug of concern in Latin America and the Caribbean, whereas the use of opiates remains the most problematic form of drug use globally. This can be attributed to the relationship between the use of opiates and injecting drug use, HIV, AIDS and overdose deaths and to the fact that the use of opiates accounts for the majority of treatment admissions for drug use in Asia and Europe.

Public perceptions about the rehabilitation of drug-dependent persons tend to oversimplify the magnitude of drug dependence. There is no quick and simple remedy for drug dependence. It is a chronic health condition and, as with other chronic conditions, the affected persons remain vulnerable for a lifetime and require long-term and continued treatment. There is a growing body of research showing that many interventions aimed at preventing the initiation of drug use (or the potential transition to drug use disorders) can be effective if they address the different personal and environmental vulnerabilities of children and young people — factors that are largely beyond a person's control.

Prevalence of HIV among people who inject drugs, 2013 or latest year available

Note: The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

A number of social and structural barriers clearly continue to hinder the access of women to treatment for drug use: globally, only one out of five drug users in treatment is a woman even though one out of three drug users is a woman. A large body of evidence has shown that social and biological factors relating to initiation of substance use, continued substance use and the development of problems related to substance use vary considerably between men and women. Men are three times more likely than women to use cannabis, cocaine and amphetamines, whereas women are more likely than men to misuse prescription opioids and tranquillizers. As the likelihood that initiation of the misuse of tranquillizers and prescription opioids may lead to regular or current use is relatively high compared with other drugs, this remains an area of particular concern for women. Available data on HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs show that, in many countries, women who inject drugs are more vulnerable to HIV infection than their male counterparts and that the prevalence of HIV is higher among women who inject drugs than among their male counterparts.

Some progress has been made towards achieving the target set in the 2011 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS of reducing by 50 per cent HIV transmission among people who inject drugs by 2015. |1| Although the number of newly diagnosed cases of HIV among people who inject drugs declined by roughly 10 per cent, from an estimated 110,000 in 2010 to 98,000 in 2013, this target is unlikely to be met.

The transmission of infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C and the occurrence of drug overdoses are only some of the risk factors that lead to the level of mortality among people who inject drugs being nearly 15 times higher than would normally be expected among people of comparable age and gender in the general population.

Not all drug overdoses are fatal; different studies have estimated that only 1 out of 20-25 overdose cases is fatal.

Non-fatal overdoses are underreported and are a common experience among drug users; however, the cumulative risk of death increases with each successive overdose.

DRUG SUPPLY AND MARKETS

The production of cannabis resin continues to be confined to a few countries in North Africa, the Middle East and South-West Asia, whereas cannabis herb is produced in most of the countries in the world. South America continues to account for practically all global cultivation of coca bush, and South-West Asia (Afghanistan) and SouthEast Asia (mainly the Lao People's Democratic Republic and Myanmar) continue to account for the vast majority of illicit opium poppy cultivation. Although the manufacture of ATS is difficult to assess, there are reports of ATS manufacture in all regions worldwide.

There may have been no major change in the regions in which illicit crop cultivation and drug manufacture take place, but the illicit drug markets and the routes along which drugs are smuggled continue to be in a state of flux. The "dark net", the anonymous online marketplace used for the illegal sale of a wide range of products, including drugs, is a prime example of the constantly changing situation, and it has profound implications for both law enforcement and drug trafficking.

A more classic example of this dynamic aspect is the continued shift in the routes used for smuggling opiates and the fact that Afghan heroin may be reaching new markets. The growing importance of Africa as a transit area for Afghan heroin bound for Europe and other regions has been reflected in increasing seizures of heroin reported in recent years in some African countries, particularly in East Africa. Recent seizures also suggest that it may have become more common for large shipments of Afghan heroin to be smuggled across the Indian Ocean into East and Southern Africa. Moreover, Africa continues to be used as a trans-shipment area for smuggling cocaine across the Atlantic into Europe, and Eastern Europe is emerging as a transit area and as a destination. The quantities being smuggled are small but this may be an indication that the cocaine market is moving eastwards.

West Africa appears to have become an established source of the methamphetamine smuggled into East and South-East Asia via Southern Africa or Europe, with new trafficking routes linking previously unconnected regional methamphetamine markets. The established market for methamphetamine in East and South-East Asia continues to grow, while there are also indications of increasing methamphetamine use in parts of North America and Europe.

As opiates originating in Myanmar may be unable to meet the demand in South-East Asia, the so-called "southern route" could be increasing in importance as a conduit for smuggling Afghan heroin southwards from Afghanistan through Pakistan or the Islamic Republic of Iran. Trafficking networks using the Balkan route to smuggle Afghan heroin into Europe may be experimenting with a new route, leading through the Caucasus, and there are indications of heroin being trafficked from Iraq rather than from the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Not only are drug trafficking routes undergoing change, but there is also evidence that organized criminal groups, which in the past may have limited their trafficking activities to one drug type, are diversifying. For example, groups that previously focused on heroin trafficking appear to be increasingly engaging in trafficking in cannabis resin and methamphetamine.

To a certain extent, there has also been a shift in the focus of the trafficking routes themselves. There is increasing evidence that routes traditionally used for smuggling one type of drug are now being used for smuggling other drug types. While there appears to be an evolution in the countries reported to be used as transit hubs for certain drugs, such as African countries being used as transit areas for heroin and cocaine, certain African countries are also increasingly being used as transit areas for different types of drugs.

Opiates

According to the limited information available, global prevalence of the use of opioids (0.7 per cent of the world's adult population, or 32.4 million users) and the use of opiates (0.4 per cent, or 16.5 million users worldwide) has remained stable, whereas global opium poppy cultivation in 2014 reached the highest level since the late 1930s. This was mainly attributable to the fact that opium poppy cultivation reached historically high levels in the main country in which opium poppy is cultivated, Afghanistan, where potential production of opium also continued to increase. Global opium production reached 7,554 tons in 2014, also the second highest level since the late 1930s, though global seizures of opium, heroin and illicit morphine decreased by 6.4 per cent from 2012 to 2013.

Global potential opium production, 1998-2014

Source: Period 1997-2002: UNODC; since 2003: national illicit crop monitoring system supported by UNODC.

Main global trafficking flows of opiates

Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire and individualdrug seizure database.

Notes: The trafficking routes represented on this map should be considered broadly indicative and based on data analyses rather than definitive route outlines. Such analyses are based on data related to official drug seizures along the trafficking route as well as official country reports and responses to annual report questionnaires. Routes may deviate to other countries that lie along the routes and there are numerous secondary flows that may not be reflected.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.The increase in estimated opium and heroin production has not yet been reflected in an increase in heroin supply in most regions. The destination of the additional quantities of heroin is unclear, but there are signs of increases in the availability of heroin and in heroin-related indicators such as mortality and medical emergencies in some countries.

The prevalence of opioid use remains high in North America (3.8 per cent) in relation to the global average. In the United States of America, there are indications of a partial shift in the use of opioids towards heroin use, attributable in part to changes in the formulation of OxyContin, one of the main prescription opioids that are misused, as well as an increase in the availability of heroin and a decrease in its price in some parts of the country. With the number of heroin-related deaths increasing considerably (from 5,925 in 2012 to 8,257 in 2013), reaching the highest level in a decade, the number of drug-related deaths continues to rise in the United States.

There are signs of change in the supply of heroin in different regions. In North America, although 90 per cent of the heroin in Canada originates in Afghanistan, the United States continues to be supplied by heroin manufactured in Central and South America. However, analysis of seizures indicates that while Afghan heroin currently accounts for relatively little of the heroin seized in the United States, this may be changing. In Oceania, there have been fluctuations in the Australian market between the supply of Afghan heroin and heroin originating in the Lao People's Democratic Republic or Myanmar, but it seems that in 2013 the latter was predominant. This underlines the fact that the reach of organized criminal networks continues to be global and that organized criminal groups are becoming increasingly sophisticated and versatile.

In Europe, the heroin market is also marked by variations, albeit at the subregional level. There are indications of a stable or downward trend in the use of heroin in Western and Central Europe, while heroin seizures have recently increased in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, where the absence of new data prevents the assessment of recent trends in the prevalence of drug use.

In the absence of any recent reliable data on the extent of the use of opioids in most parts of Asia, it is difficult to determine a trend, but the use of opioids is generally considered to be stable. Asia remains the world's largest market for opiates, accounting for an estimated two thirds of all users of opiates, and the total number of registered heroin users in China is increasing. Data on Africa remain limited, but it is likely that the increasing importance of the region as a transit area for Afghan heroin bound for markets in other regions has had an impact on the use of opiates in Africa.

Cocaine

Main global trafficking flows of cocaine

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire and individual drug seizure database.

Notes: The trafficking routes represented on this map should be considered broadly indicative and based on data analyses rather than definitive route outlines. Such analyses are based on data related to official drug seizures along the trafficking routes as well as official country reports and responses to annual report questionnaires. Routes may deviate to other countries that lie along the routes and there are numerous secondary flows that may not be reflected.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.Not only did coca bush cultivation continue to decline in 2013, reaching the lowest level since the mid-1980s, when estimates first became available, but the annual prevalence of cocaine use (0.4 per cent of the adult population) also continued to decline in Western and Central Europe and North America. In those subregions, which, along with South America, have the world's largest cocaine markets, the prevalence of cocaine use is highest. Supply reduction measures may have contributed to the decline in coca bush cultivation in the coca-producing countries, leading to a reduction in the availability of cocaine and the shrinking of some of the principal cocaine markets.

Coca bush cultivation, 2003-2013

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire and other official sources.

In addition to the human cost of cocaine manufacture and trafficking, illicit coca bush cultivation and the transformation of coca into cocaine continue to cause serious environmental damage even though coca bush cultivation has decreased. In Colombia alone, roughly 290,000 hectares of forest were lost as a direct result of coca crop cultivation between 2001 and 2013, while the slash-and-burn method used to clear new plots has led to increased erosion. Further environmental damage has been caused by the herbicides and fertilizers used in coca bush cultivation and the chemicals employed in the transformation of coca into cocaine.

Cannabis

Cannabis use is increasing and continues to be high in West and Central Africa, Western and Central Europe and Oceania, as well as in North America, where the most recent data available indicate an increase in the prevalence of cannabis use in the United States. Europe is still one of the world's largest markets for cannabis resin, but its use is concentrated in a few countries. The use of cannabis herb is more evenly spread across European countries, and the market in Western and Central Europe is shifting from cannabis resin to cannabis herb.

Advances in cannabis plant cultivation techniques and the use of genetically selected strains have led to an increase in the number of cannabis harvests, as well as in the yield and potency of cannabis. The potency of cannabis, commonly measured in terms of the concentration of THC (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive ingredient in cannabis), has been increasing in many markets over the past decade, leading to growing concern about the potential of cannabis to cause serious health problems. Despite the fact that increasing professionalism and sophistication have enhanced the capacity of cannabis plant growers to avoid detection by law enforcement authorities, data for 2013 show an increase in the quantities of cannabis herb and cannabis resin seized worldwide.

Synthetic drugs: amphetamine-type stimulants and new psychoactive substances

The global market for synthetic drugs continues to be dominated by methamphetamine. The increasingly diversified market for methamphetamine is expanding in East and South-East Asia, where it accounts for a large share of the people receiving treatment for drug use in a number of countries, and use of crystalline methamphetamine is increasing in parts of North America and Europe. Surging seizures since 2009 also point to a rapid expansion in the global ATS market, with the total quantity of seized ATS almost doubling to reach over 144 tons in 2011 and 2012, the highest level since the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) began systematic monitoring, and remaining at a comparatively high level in 2013.

Methamphetamine flows as perceived by recipient countries, 2011-2013

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire, 2011-2013.

Note: The origins of the flow arrows do not necessarily indicate the source/manufacture of methamphetamine. These arrows represent the flows as perceived by recipient countries. Flow arrows represent the direction of methamphetamine trafficking and are not an indication of the quantity trafficked.

The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

Number of new psychoactive substances reported, 2009-2014

Source: UNODC, early warning advisory on NPS, 2009-2014.

Note: This graph represents only the number of different NPS reported during the respective reporting year. Not all NPS reported in one year were necessarily reported in the following year(s).

According to seizure data, the global "ecstasy" market is smaller than the global market for amphetamine and methamphetamine and remains confined to a few regions. East and South-East Asia and Oceania may be emerging as a driver of the global market for "ecstasy", while the market seems to be on the decline in the Americas, where "ecstasy" seizures dropped by 81 per cent between 2009 and 2012. The largest "ecstasy" markets continue to be East and South-East Asia and Oceania, although seizures of "ecstasy" declined there in 2013.

The "ecstasy" market has been on the decline in several European countries for some time, with mephedrone and other NPS perhaps serving as a substitute. The use of mephedrone and synthetic cannabinoids may have declined in some markets in recent years, but a growing number of countries have reported a wider range of emerging NPS, as well as worrying developments such as the injecting use of NPS. There continue to be limited data on recent developments in injecting drug use and polydrug use involving NPS; these particular forms of drug use could pose a serious challenge for providers of treatment for drug use and health-care providers.

The sheer number, diversity and transient nature of NPS currently on the market partly explain why there are still only limited data available on the prevalence of use of many NPS. Those difficulties also explain why both the regulation of NPS and the capacity to address health problems related to NPS continue to be challenging. Different countries report that NPS continue to proliferate in the marketplace, in terms of both quantity and diversity. By December 2014, a total of 541 NPS had been reported by 95 countries and territories to the UNODC early warning advisory. Synthetic cannabinoids continued to account for the majority of NPS reported in 2014 (39 per cent); they were followed by phenethylamines (18 per cent) and synthetic cathinones (15 per cent). The growing number of NPS available worldwide indicates that the market for synthetic drugs is becoming even more diversified.

ALTERNATIVE DEVELOPMENT

Illicit crop cultivation: breaking the vicious cycle

Illicit crop cultivation is driven by situation-specific combinations of vulnerability and opportunity factors. As survival and subsistence are real considerations for many households that engage in illicit crop cultivation, they are frequently risk-averse and take into account a variety of factors when making decisions on such cultivation.

One of those factors is the specific nature of the illicit crops — agronomic aspects, durability of the product, price, ease of sale, etc. All major illicit crops are particularly attractive because they produce quick returns from non-perishable products. Illicit crop cultivation can thus provide farmers with the necessary short-term economic means to survive, but it does not allow the area to develop its licit economy and institutional environment.

Other factors include geographical and environmental factors, such as climate, the availability of water and arable land, and proximity to market; household-specific socioeconomic factors, such as level of income, existing employment opportunities, access to credit and size of landholding; developmental facilities such as access to roads, the power grid and educational and health services; and sociopolitical and institutional factors, such as security, government control and rule of law. Illicit crop cultivation tends to take place in marginalized, isolated areas characterized by limited government control, unclear land rights, lack of infrastructure, poverty and violence, which are areas where few international development agencies tend to operate.

Impact of illicit drug production and of alternative development interventions

Alternative development is an approach aimed at reducing the vulnerabilities that lead to involvement in illicit crop cultivation and ultimately eliminating such cultivation. Alternative development can break the vicious cycle of rising illicit drug production, weakening rule of law, decreasing growth of the licit economy, decreasing investment in licit sectors, strengthening organized crime and increasing violence by effectively promoting factors fostering a sustainable licit economy. In the long run, this can attract investment and help to develop the necessary infrastructure, thereby changing and sustaining the livelihood of rural communities.

Alternative development is not generally an objective in itself but rather a means to an end: it is aimed at contributing to an enabling environment for long-term rural development without illicit crop cultivation. Alternative development acts as a catalyst, boosting development in areas with particular challenges related to the illicit drug economy.

The General Assembly at its twentieth special session, held in 1998, defined alternative development as a process to prevent and eliminate illicit crop cultivation "through specifically designed rural development measures in the context of sustained national growth and sustainable development efforts in countries taking action against drugs, recognizing the particular sociocultural characteristics of the target communities and groups". |2| This definition is used at the international level. Different definitions reflecting new strategies and approaches of alternative development have been developed by a wide variety of implementing countries, donors and practitioners.

Member States implementing domestic alternative development projects (as reported to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime), 2010-2013

Sources: UNODC annual report questionnaire and UNODC alternative development projects.

Note: Only countries providing sufficient information on the implementation of alternative development projects are included. The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

National strategies or plans employ a balanced approach, complementing alternative development not only with other supply reduction strategies (particularly law enforcement and interdiction), but also with demand reduction strategies (prevention, treatment and rehabilitation). Another commonly integrated strategy — sometimes appearing as a cross-cutting theme or a separate policy — is the promotion of good governance or the strengthening of state institutions or the rule of law.

Where is alternative development implemented?

The bulk of alternative development is implemented in all the main coca- and opium-producing countries, as well as in some cannabis-producing countries and some minor opium-producing countries, which are located in South America, Central America, the Caribbean, Asia and Africa. A number of countries in Asia, Central America, Africa and Europe have also reported plans to implement alternative development activities (see map above).

Elements of alternative development

Alternative development is promulgated at the international level, but the evolution of alternative development is driven at the country or even the local level. As the factors that push farmers towards illicit crop cultivation can differ greatly from one country or area to another, the strategic elements of alternative development must be tailored to the particular circumstances on the ground at the local level. No two alternative development projects or interventions are exactly alike, even if they are in the same area, but there are commonalities.

These general strategic elements are often similar and there are commonalities in the overall framework and approach, but the importance of their roles may vary from project to project and some may not feature at all. Success is very situation-specific and there is no manual or blueprint for alternative development. With the adoption of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Alternative Development, |3| there is now a set of general guidelines outlining good practices in planning and implementing alternative development. The major components that feature, to a greater or lesser extent, in most alternative development projects are as follows:

- Income-generating alternatives are at the core of alternative development, as economic necessity tends to play an important role in a farmer's decision on whether to engage in illicit crop cultivation. Income-generating alternatives need to be viable and sustainable in order to decrease dependence on illicit crop cultivation.

- The marketing of products of alternative development is an important component of any project. To enhance marketing options and reduce some of the vulnerabilities related to illicit crop cultivation, alternative development programmes often try to involve the private sector. This approach has enabled products of alternative development to have access to markets not only at the local and national levels, but also at the international level.

- Long-term political and financial support is essential to the success of alternative development. Time is needed not only to address the economic drivers behind illicit crop cultivation, but also to build trust with local communities and to develop long-term investment. Direct participation by farmers and communities plays a key role in the design and planning of alternative development activities, especially in areas where no public institutions can fulfil such a role.

- Land tenure and the sustainable management and use of land are crucial to the long-term success of alternative development, as lack of access to land can be one of the drivers of illicit crop cultivation. As they require several years to produce yields, most alternative cash crops require the long-term engagement of farmers; without access to land, however, farmers are reluctant to cultivate long-term cash crops.

- Environmental protection plays an increasingly important role. Alternative development has both a component of "do no harm", trying to minimize the environmental impact of alternative development interventions, and a proactive component, in which programmes directly or indirectly contribute to the protection of the environment and biodiversity and the mitigation of climate change.

Trends in global commitments to providing development assistance and alternative development made by donor countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1998-2013

Source: OECD, International Development Statistics online database (data extracted on 19 December 2014).

What is successful alternative development?

Measuring the coverage, quality and effectiveness of alternative development interventions and services with regard to addressing the drug problem is challenging. The long-term nature of alternative development interventions is a factor in the complexity of measuring their success. Experience has shown that the success of alternative development in terms of the sustainable reduction of illicit crop cultivation can only be determined after several years of intervention. Attempts to gauge success over shorter periods have been found to be counterproductive, particularly when the resulting information is used for immediate action. The fact that projects take place at the local level but their impact is often evaluated at the national level can also affect perceptions of whether an alternative development programme has been successful or not.

In assessing alternative development programmes, indicators related to human development, socioeconomic conditions, rural development and the alleviation of poverty, as well as institutional and environmental indicators, have been applied, in order to ensure that the outcomes are in line with national and international development objectives, including the Millennium Development Goals. Furthermore, efforts have been undertaken to consolidate a set of indicators that can be used to monitor the impact of alternative development.

In some cases, long-term commitment to alternative development has resulted in a sustainable reduction in illicit crop cultivation in the country or area concerned. More than 40 years of experience with alternative development have shown that it works when there is a long-term vision, adequate funding and the political support to integrate it into a broader development and governance agenda. Sustainable results in reducing illicit crop cultivation in different communities throughout the world have been obtained when the socioeconomic development of communities and the livelihood of rural households have improved.

Political commitment

Despite the considerable attention given to alternative development at the international level, the political support has not translated into continued funding from donor countries. Alternative development has featured prominently in documents prepared for the Commission on Narcotic Drugs and the special sessions of the General Assembly on the world drug problem; however, funding for alternative development has decreased considerably in the past few years. The twentieth special session of the General Assembly, held in 1998, triggered renewed impetus in funding alternative development in the spirit of "shared responsibility", but overall gross disbursements of alternative development funds from member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have declined by 71 per cent since the adoption of the 2009 Political Declaration and Plan of Action on International Cooperation towards an Integrated and Balanced Strategy to Counter the World Drug Problem. |4| In 2013, those disbursements accounted for just 0.1 per cent of global development assistance.

Over the past four decades, alternative development has been largely funded by external donors, including OECD member countries in North America, Europe and Oceania and non-member countries such as China, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Saudi Arabia and Thailand. But in recent years, South American countries such as Bolivia (Plurina-tional State of), Colombia and Peru and Asian countries such as Thailand have been increasingly using domestic funding to support alternative development activities.

In the process of connecting "local to global" that is currently taking place, best practices and lessons learned from local experiences within national strategies are exchanged. This reinforces efforts by UNODC, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs and other entities to foster more South-South cooperation (a broad framework for collaboration among countries of the South), pursuant to the United Nations Guiding Principles on Alternative Development.

The way forward

Alternative development has contributed to economic development (mostly in rural areas) in order to target the underlying factors and root causes of illicit drug economies. The new sustainable development goals (the post-2015 development agenda) may bring a new vision and provide alternative development with a new theoretical framework, in addition to socioeconomic development — its "traditional" pillar.

The new development agenda, emerging from the report of the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals, |5| points to the crucial role of environmental protection and recognizes that secure and equitable rights to land and natural resources are central to the achievement of sustainable development. These and other elements such as the rule of law and "effective, accountable and inclusive institutions", as described in goal 16 in the report, are, in part, already addressed by alternative development.

Different national experiences have shown that there may be opportunities for the alternative development approach to be applied to counter illegal activities other than illicit crop cultivation. Alternative development could be used to support communities affected by, for example, drug trafficking, illegal mining or wildlife and forest crime. With these broader applications, the concept of alternative development could be extended well beyond the existing "preventive alternative development" strategy that targets areas at risk of being used for illicit crop production.

CHAPTER I

STATUS AND TREND ANALYSIS OF ILLICT DRUG MARKETSOverall drug use remains stable globally

It is estimated that almost a quarter of a billion people between the ages of15 and 64 years used an illicit drug in 2013. This corresponds to a global prevalence of 5.2 per cent (range: 3.4-7.0 per cent), suggesting that drug use has remained stable in the past three years, although the estimated number of drug users has actually risen by 6 million to 246 million (range: 162 million-329 million) owing to the increase in the global population. With some 27 million people (range: 15.7 million-39 million), or 0.6 per cent of the population aged 15-64, estimated to suffer from problem drug use, including drug-use disorders or drug dependence, problem drug use seems to have remained somewhat stable over this three-year period.

FIG. 1. Global trends in the estimated number of drug users, 2006-2013

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

Note: Estimates are for adults (aged 15-64), based on past-year use.FIG. 2. Global trends in the estimated prevalence of drug use, 2006-2013

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

Note: Estimated percentage of adults (aged 15-64) who have used drugs in the past year.

FIG. 3. Global trends in the prevalence of use of various drugs, 2009-2013

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

Note: Based on the estimated percentage of adults (aged 15-64) who have used the substance in the past year.

TABLE 1. Global estimates of the use of various drugs, 2013

Percentage of population that has used the drug Number of users (thousands) low high low high Cannabis 2.7 4.9 128,480 232,070 Opioids 0.6 0.8 27,990 37,560 Opiates 0.3 0.4 12,920 20,460 Cocaine 0.3 0.4 13,800 20,730 Amphetamines 0.3 1.1 13,870 53,870 "Ecstasy" 0.2 0.6 9,340 28,390 All illicit drug use 3.4 7.0 162,000 329,000 Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

Note: Estimates for adults aged 15-64, based on past-year use.

UNDERSTANDING TRENDS IN DRUG USE Global and regional trends in drug use are estimated from nationally representative surveys that include questions on drug use, as well as from information gathered through studies that use indirect methods to estimate the number of regular or high-risk users such as problem opioids users. Household surveys on drug use are expensive and are, at best, carried out every three to five years. Many countries do not conduct such surveys on a regular basis and many others, especially in Asia and Africa, do not conduct them at all. In these cases, estimates from the limited number of countries where data are available are used to compute regional and global estimates.ª

Rather than real-time trends at the global and regional levels, year-on-year changes in drug-use estimates thus reflect updated information from countries where new data were made available. These changes may be especially misleading if updated information is available only in countries with large populations. Indeed, global and regional estimates of drug use, including by substance, are heavily shaped by countries with large populations because of the use of national drug-use data weighted by population size in the calculation of the estimates. The stable trend that can be calculated with existing data, may mask variations that are happening in large countries for which data are not available. In addition, the estimated number of drug users is further influenced by changes in estimates of the global population aged 15-64.

The global and regional estimates of the extent of drug use offered in the present report should be viewed as best estimates, noting that they reflect the best available information at the time of analysis. From a global policy perspective, it would be more prudent to look at long-term trends rather than year-on-year changes, which may be merely a reflection of changes in a few countries. Furthermore, particular caution is required when considering trends in problem drug-use estimates at the global level, as the extent of problem drug use is difficult to capture in general population surveys (which are used to estimate drug use), and indirect methods, which are often complex, are therefore used to obtain these estimates.

ª For further information, see the methodology section in the online version of this report.

Notwithstanding both regional and national variations in trends in the use of different types of drug, cannabis use has continued to rise since 2009, while the use of opioids, including the use of heroin, opium and the non-medical use of pharmaceutical opioids, has stabilized at high levels (see figure 3). However, the use of cocaine and amphetamines has declined overall, although that is mainly a reflection of trends in the Americas and Europe.

Problem drug use as reflected in the demand for drug treatment

FIG. 4. Percentage distribution of people in treatment, by primary drug type, by region and share of first-time entrants for each drug type (2013 or latest available data)

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

In the absence of data on patterns of problem drug use, data on drug users in treatment are taken as a proxy. Treatment demand for different substances varies by region, but almost half of the people who access treatment for drug use are first-time entrants. The proportion of first-time entrants in treatment for ATS and cannabis use disorders in 2013 was higher than for other substances in most regions, indicating that, compared with other substances, there is an expanding generation of ATS and cannabis users who need treatment (see figure 4). In Asia, the number of people accessing treatment for cannabis-use disorders is small, but the proportion of first-time entrants among them (62 per cent) is the largest. Compared with other regions where cannabis users in treatment are typically in their twenties, in Asia they are reported to be typically in their thirties. As observed elsewhere, |1| |2| this may reflect a cohort of long-term regular users of cannabis who seek treatment for cannabis-related problems. In Europe, North America and Oceania, the proportion of first-time entrants for cannabis-use disorders is high, but they tend to be in their twenties. A large share of cannabis users in treatment may reflect cannabis users referred by the criminal justice system, whereas opioid users in treatment are relatively older (in their thirties). In Western and Central Europe, 16 per cent of first-time entrants were seeking treatment for opioid use, and overall treatment demand remains high, which reflects an ageing cohort of opioid users in treatment: of the estimated 1.5 million opioid users in Europe, 700,000 received opioid substitution therapy in 2012. |3| The high proportion of people in treatment for opioid use in Asia and Eastern Europe reflects the extent of problem opioid use in those regions, and ATS users form another group with a high proportion of first-time entrants in treatment in Asia.

Prison is a high-risk environment for drug use

On any given day, more than 10.2 million people are held in penal institutions throughout the world, mostly as pretrial detainees or remand prisoners, or as sentenced prisoners. |4| However, because of the high transfer of people between prison and the wider community, the number of people who spend at least some time in prison each year is considerably greater. The rapid turnover of a large number of people between the prison environment and their wider communities outside prison means that prison health merits consideration as an integral part of public health.

Drug use, including heroin use, and drug injection are common in prisons

FIG. 5. Lifetime, annual and past-month prevalence of drug use in prisons (based on 62 studies from 43 countries over the period 2000-2013)

Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire; and C. Carpentier, L. Royuela and L. Montanari, "The global epidemiology of drug use in prison" (2015).

Note: Symbols represent median prevalence with vertical lines depicting inter-quartile range. Data on lifetime, annual and past-month use are not consistent across studies (this explains why the annual prevalence of cocaine use has a median value lower than the past-month use).People who use drugs often have a history of incarceration. In the United States of America, for example, it is estimated that between 24 and 36 per cent of all people using heroin pass through the correctional system each year, representing more than 200,000 individuals. |5| Although data remain limited, studies have shown that drug use within prisons is common (see figure 5). Based on a review of 41 studies from 26 countries (mostly in Europe) and supplemented with data reported in responses from Member States to the annual report questionnaire, drug use in prisons was shown to be highly prevalent in many of these studies, although there is considerable variability. |6| Approximately one in three people held in prison have used drugs at least once while incarcerated, with approximately one in eight reporting use in the past month. Cannabis is the most commonly used drug, as it is in the wider community outside prison, but lifetime and recent (past-month) use of heroin in prison is more common than that of cocaine, amphetamines or "ecstasy". Based on these studies, the median estimate of the proportion of people held in prison who have used heroin at some time while incarcerated is 10.1 per cent (inter-quartile range: 2.5-13.4 per cent), while 5.0 per cent (inter-quartile range: 0.8-11.5 per cent) report use in the past year (which is approximately 14 times higher than in the general population, estimated at 0.35 per cent), and 2.4 per cent (inter-quartile range: 1.3-9.0 per cent) report recent use in the past month.

A number of studies report high levels of injecting drug use by prisoners, which may be a result of the high prevalence of heroin use. |7| In Europe, of the 12 countries reporting to EMCDDA on injecting drug use by prisoners at some time during incarceration, four countries report levels above 10 per cent (Luxembourg, 31 per cent; Germany, 22 per cent; Portugal, 11 per cent; and Latvia, 10 per cent). |8| Some small-scale surveys provide anecdotal information on high levels of injecting drugs in prison. For example, among a survey of female prisoners in British Columbia, Canada, 21 per cent reported injecting drugs while in prison; |9| a survey of prisoners in Australia revealed that 23 per cent had injected drugs at some time in prison; |10| and among male inmates in Bangkok, 39 per cent reported injecting drugs while in prison, with 12 per cent injecting for the first time while incarcerated. |11| These estimates are considerably higher than the prevalence of injecting drug use among the general population, which is estimated globally to be 0.26 per cent of those aged 15-64.

Unsafe injecting practices are a major risk factor for the transmission of blood-borne infections such as HIV and viral hepatitis B and C. Due to the difficulties of obtaining sterile needles and syringes, people held in prisons are more likely to share injecting equipment and this practice has been found to be extremely common among prisoners. Very high levels of sharing of needles and syringes have been documented among people who inject drugs (PWID) in prisons: 56 per cent in Pakistan, 66 per cent in the Russian Federation, 70-90 per cent in Australia, 78 per cent in Thailand and 83-92 per cent in Greece. |12|

Millions of people inject drugs worldwide

Among people using drugs, PWID are one of the most vulnerable and marginalized groups. They experience a range of health, socioeconomic and legal challenges, often with poor outcomes, not least of which is the elevated risk of death compared with the general population (see also box 3). The joint UNODC/WHO/UNAIDS/World Bank estimate for the number of PWID worldwide for 2013 is 12.19 million (range: 8.48-21.46 million). This corresponds to 0.26 per cent (range: 0.18-0.46 per cent) of the adult population aged 15-64. This estimate is based on reporting of information on current injecting drug use from 93 countries covering 84 per cent of the global population aged 15-64.

HIGH RATES OF HIV, TUBERCULOSIS AND HEPATITIS C ARE OFTEN FOUND IN PRISONS

Prevalence of HIV among people held in prison, by region (2013, or latest year available after 2008)

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire; and Dolan and others, "HIV/AIDS in prison" (2014).

Notes: Symbols represent median prevalence with vertical lines depicting inter-quartile range. Only two studies were identified from Oceania (Australia and New Zealand).Prisons pose a high-risk environment for the transmission of infectious diseases, particularly HIV and tuberculosis. In many countries, PWID, who are at increased risk of contracting HIV and other bloodborne infections, compared with the population in the community, are overrepresented in prison populations.ª The global median prevalence of HIV among people living in prisons is estimated at 3.0 per cent, which is five times higher than the global median prevalence of HIV of 0.6 per cent among the general population aged 15-49.b

Prison settings are often characterized by overcrowding, inadequate ventilation, poor nutrition and limited medical facilities for diagnosis and treatment, all of which contribute to the spread of tuberculosis among prisoners. In some countries, the incidence rates of tuberculosis in prisons were found to be 8-35 times higher than among the general populations.c Combined infections of HIV and tuberculosis are particularly serious, with each infection speeding up the progress of the other. The risk of developing tuberculosis is 20-37 times greater in people living with HIV compared with those not infected with HIV.d In addition, the prevalence of hepatitis C is far higher among people held in prison, particularly among those in prison with a history of injecting drug use.e

ª Kate Dolan and others, "HIV/AIDS in prison: A global systematic review of prevalence, incidence, AIDS related mortality and HIV and related interventions", presented at the 20th International Conference on AIDS, held in Melbourne, Australia, from 20 to 25 July 2014.

b UNAIDS, AIDSinfo database.

c A. Aerts and others, "Tuberculosis and tuberculosis control in European prisons", International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, vol. 10, No. 11 (2006), pp. 1215-1223.

d Masoud Dara, Dato Chorgoliani and Pierpaolo de Colombani, "TB prevention and control care in prisons", in Prisons and Health, S. Enggist and others, eds. (Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2014).

e S. Larney and others, "The incidence and prevalence of hepatitis C in prisons and other closed settings: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis", Hepatology, vol. 58, No. 4 (2013), pp. 1215-1224.

The updated global total number of PWID is slightly different from the 12.69 million (for 2012) published in the World Drug Report 2014. Although new or more recent information on PWID from 22 countries are included, the revision primarily reflects new estimates for Poland and the United Republic of Tanzania, which were not previously reported, and lower estimates for the numbers of PWID in Brazil and Viet Nam. The global prevalence of PWID among the population aged 15-64 is essentially unchanged from the World Drug Report 2014.

By far the highest prevalence of PWID continues to be found in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, where 1.27 per cent of the general population aged 15-64 is estimated to be injecting drugs, a rate nearly five times the global average. The estimate for this subregion is heavily influenced by the high prevalence of injecting drug use experienced in the Russian Federation (2.29 per cent of the population aged 15-64). However, in terms of the actual numbers of PWID, the largest proportion continues to reside in East and South-East Asia, with an estimated 3.15 million, accounting for approximately one in four PWID worldwide. Large numbers of PWID also reside in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe (2.91 million, representing 24 per cent of the global total number of PWID) and North America (2.07 million, representing 17 per cent of the global total number of PWID). Three countries, the Russian Federation, China and the United States, when combined, account for nearly half (48 per cent) of the global total number of PWID.

TABLE 2. Estimated number and prevalence (percentage) of people who currently inject drugs among the general population aged 15-64, 2013

Region Subregion People who inject drugs Estimated number Prevalence (percentage) low best high low best high Africa 330,000 1,000,000 5,590,000 0.05 0.16 0.91 America 2,150,000 2,820,000 3,970,000 0.34 0.44 0.62 North America 1,780,000 2,070,000 2,380,000 0.56 0.65 0.75 Latin America and the Caribbean 370,000 750,000 1,590,000 0.11 0.23 0.49 Asia 3,380,000 4,560,000 6,110,000 0.12 0.16 0.21 Central Asia and Transcaucasia 360,000 410,000 470,000 0.66 0.75 0.87 East and South-East Asia 2,330,000 3,150,000 4,300,000 0.15 0.20 0.27 South-West Asia 400,000 670,000 940,000 0.22 0.37 0.51 Near and Middle East 30,000 70,000 130,000 0.03 0.08 0.13 South Asia 250,000 260,000 260,000 0.03 0.03 0.03 Europe 2,500,000 3,680,000 5,630,000 0.45 0.67 1.02 Eastern and South-Eastern Europe 1,790,000 2,910,000 4,780,000 0.78 1.27 2.09 Western and Central Europe 710,000 770,000 850,000 0.22 0.24 0.26 Oceania 120,000 130,000 160,000 0.49 0.53 0.66 GLOBAL 8,480,000 12,190,000 21,460,000 0.18 0.26 0.46 Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire; progress reports of UNAIDS on the global AIDS response (various years); the former Reference Group to the United Nations on HIV and Injecting Drug Use; and national government reports.

Note: Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10,000.The burden of HIV among people who inject drugs continues to be high in many regions

The burden of HIV among PWID is high, with PWID accounting for an estimated 30 per cent of new HIV infections outside sub-Saharan Africa. |13| About 1.65 million (range: 0.92-4.42 million) PWID were estimated to be living with HIV worldwide in 2013, which would correspond to 13.5 per cent of PWID being HIV positive. This joint UNODC/WHO/UNAIDS/World Bank estimate is based on information on the prevalence of HIV among PWID from 114 countries, covering 93 per cent of the estimated global number of PWID.

Although estimates of the prevalence of HIV among PWID have been updated for 52 countries (none with large numbers of PWID living with HIV), the global total number of PWID living with HIV is essentially unchanged from the information provided in the World Drug Report 2014. However, the small downward revision to the total number of PWID globally has resulted in the global prevalence of HIV among PWID being revised upwards to 13.5 per cent (from the 13.1 per cent presented in the World Drug Report 2014).

Two subregions stand out as having particularly high rates of HIV infection among PWID. An estimated 29 per cent of PWID are living with HIV in South-West Asia and some 23 per cent of PWID are living with HIV in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. In the remaining regions, the average prevalence of HIV infection among PWID is much lower, ranging from 1 per cent in Oceania to 11 per cent in Africa (although for Africa this estimate may not be reliable as monitoring systems may not be adequate).

Approximately 40 per cent of the estimated global total number of PWID living with HIV reside in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, mostly in the Russian Federation and Ukraine. East and South-East Asia contribute a further 20 per cent to the global total number of PWID living with HIV, although both the prevalence of injecting drug use and the prevalence of HIV among PWID are below their respective global averages. It is the large population aged 15-64 residing in this region that translates into the relatively large number of PWID living with HIV. South-West Asia, the region with the highest prevalence of HIV among PWID, contributes 12 per cent to the total global number of PWID living with HIV, with a large proportion of these residing in Pakistan. Four countries, the Russian Federation, China, Pakistan and the United States (in descending order), when combined account for nearly two thirds (63 per cent) of the total global estimated number of PWID living with HIV.

TABLE 3. Estimated number and prevalence (percentage) of HIV among people who inject drugs, 2013

Region Subregion HIV among people who inject drugs Estimated number Prevalence (percentage) Best estimate low best high Africa 30,000 112,000 1,582,000 11.2 America 167,000 237,000 416,000 8.4 North America 141,000 182,000 248,000 8.8 Latin America and the Caribbean 26,000 55,000 168,000 7.3 Asia 344,000 576,000 993,000 12.6 Central Asia and Transcaucasia 26,000 31,000 40,000 7.5 East and South-East Asia 211,000 329,000 612,000 10.5 South-West Asia 90,000 196,000 314,000 29.3 Near and Middle East 1,000 3,000 9,000 3.8 South Asia 17,000 17,000 18,000 6.8 Europe 373,000 724,000 1,428,000 19.7 Eastern and South-Eastern Europe 322,000 665,000 1,359,000 22.8 Western and Central Europe 51,000 59,000 69,000 7.6 Oceania 1,000 1,000 2,000 1.0 GLOBAL 915,000 1,651,000 4,421,000 13.5 Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire; progress reports of UNAIDS on the global AIDS response (various years), the former Reference Group to the United Nations on HIV and Injecting Drug Use; estimates based on UNODC data; and national government reports.

Note: Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10,000.FIG. 6. People who inject drugs living with HIV, in relation to the prevalence (percentage) of people who inject drugs and the prevalence (percentage) of HIV among this group, by region, 2013

Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire; progress reports of UNAIDS on the global AIDS response (various years); the former Reference Group to the United Nations on HIV and Injecting Drug Use; and national government reports.

Notes: The number of PWID living with HIV is represented for each region as both a proportion of PWID in the general population aged 15-64 (horizontal axis) and as a proportion of PWID living with HIV (vertical axis). The areas of the circles are proportional to the number of PWID living with HIV. The orange dot and dashed lines represent the global average prevalence of PWID and the global average prevalence of PWID living with HIV.

FIG. 7. Prevalence of HIV among people who inject drugs in selected cities

Sources: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire; progress reports of UNAIDS on the global AIDS response (various years); the former Reference Group to the United Nations on HIV and Injecting Drug Use; and national government reports.

The Russian Federation is affected by a concentrated HIV epidemic among PWID. Approximately one in three PWID living with HIV worldwide are estimated to reside in the Russian Federation, which experiences both a high prevalence and a high incidence |14| (new cases) of HIV among PWID. However, across cities in the Russian Federation there is a very large variation in the HIV prevalence among PWID. A study carried out in eight cities in the period 2007-2009 showed percentages of PWID living with HIV ranging from levels below 10 per cent in Voronezh (3 per cent) and Omsk (9 per cent), to around 15 per cent in Naberezhnye Chelny (13 per cent), Chelyabinsk and Orel (both 15 per cent), to around 60 per cent in Irkutsk (57 per cent), Saint Petersburg (59 per cent) and Yekaterinburg (64 per cent). |15|

The prevalence of HIV among PWID can vary markedly between cities (see figure 7) and certain cities and settings around the world that carry a large proportion of the global burden of HIV are becoming a focus of attention in the global response to the HIV epidemic, |16| with the geographically localized nature of HIV epidemics and the role of cities and settings, such as prisons, increasingly being seen as critical considerations.

Availability of harm reduction services remains low

FIG. 8. Levels of service coverage for people who inject drugs and those among them living with HIV (2013, or latest year available)

Source: UNODC, responses to annual report questionnaire.

Note: For further information, see the methodology section in the online version of this report.In many countries, the levels of service coverage for needle and syringe programmes, opioid substitution therapy and antiretroviral therapy remain low, as defined according to targets set by WHO, UNODC and UNAIDS (see figure 8). |17| The proportion of countries reporting these services as either not available or at low levels of coverage are 47 per cent, 41 per cent and 22 per cent, respectively. Most of the countries reporting information on service coverage are in Europe where the levels of service coverage are relatively high. Outside Europe the level of access to these services is much lower. |18|