| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

Nov14

See Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2016

See Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2012Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2014

Back to ContentsCONTENTS

Core results

Executive summary

Introduction

MethodologyTraffickers

Trafficking Victims

Forms of Exploitation

Trafficking Flows

Traffickers, Organized Crime and the Business of Exploitation

The Response to Trafficking in PersonsTrafficking in Persons in Europe and Central Asia

Trafficking in Persons in the Americas

Trafficking in Persons in South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific

Trafficking in Persons in Africa and the Middle EastText boxes

Origin or destination country?

Intimate and/or close family relationships and trafficking in persons offending

Towards a global victim estimate?

Recruitment through feigned romantic relationships

Trafficking in persons and armed conflicts

Confiscated assets and compensation of human trafficking victims

Do confraternities control the trafficking of Nigerian victims in Europe?MAPS

MAP 1: Share of foreign offenders among the total number of persons convicted of trafficking in persons, by country, 2010-2012

MAP 2: Share of children among the number of detected victims, by country, 2010-2012

MAP 3: Countries that report forms of exploitation other than forced labour, sexual exploitation or organ removal, 2010-2012

MAP 4: Shares of detected victims who are trafficked into the given country from another subregion, 2010-2012

MAP 5: Shares of detected victims by subregional and transregional trafficking, 2010-2012

MAP 6: Main destination areas of transregional trafficking flows (in blue) and their significant origins, 2010-2012

MAP 7: Citizenships of convicted traffickers in Western and Central Europe, by subregion, shares of the total, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

MAP 8: Origins of victims trafficked to Western and Central Europe, by subregion, share of the total number of victims detected there, 2010-2012

MAP 9: Origins of victims trafficked to Western and Southern Europe, share of the total number of victims detected there, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

MAP 10: Origins of victims trafficked to Central Europe and the Balkans, share of the total number of victims detected there, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

MAP 11: Destinations of trafficking victims from Central Europe and the Balkans, as a proportion of the total number of victims detected at specific destinations, 2010-2012

MAP 12: Destinations of trafficking victims from Eastern Europe and Central Asia, as a proportion of the total number of victims detected at destination, 2010-2012

MAP 13: Origins of victims trafficked into North and Central America and the Caribbean, shares of the total number of victims detected, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

MAP 14: Destinations of trafficking victims originating in North and Central America and the Caribbean, proportion of the total number of detected victims at destinations, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

MAP 15: Origin of victims detected in South America, as a proportion of the total number of victims detected in the subregion, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

MAP 16: Destinations of trafficking victims originating in South America, proportion of the total number of detected victims at destinations, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

MAP 17: Destinations of trafficking victims originating in East Asia and the Pacific, proportion of the total number of detected victims at destinations, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

MAP 18: Destinations of trafficking victims originating in South Asia, proportion of the total number of detected victims at destinations, 2010-2012

MAP 19: Destinations of trafficking victims originating in West Africa, proportion of the total number of detected victims at destinations, 2010-2012

MAP 20: Destinations of trafficking victims originating in East Africa, proportion of the total number of detected victims at destinations, 2010-2012

MAP 21: Origins of victims trafficked to the Middle East, proportions of the total number of victims detected there, 2010-2012

MAP 22: Destinations of trafficking victims originating in North Africa, proportion of the total number of detected victims at destinations, 2010-2012

PREFACE

The exploitation of one human being by another is the basest crime. And yet trafficking in persons remains all too common, with all too few consequences for the perpetrators.

Since 2010, when the General Assembly mandated UNODC to produce this report under the UN Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons, we have seen too little improvement in the overall criminal justice response..

More than 90% of countries have legislation criminalizing human trafficking since the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, under the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, came into force more than a decade ago.

Nevertheless, this legislation does not always comply with the Protocol, or does not cover all forms of trafficking and their victims, leaving far too many children, women and men vulnerable. Even where legislation is enacted, implementation often falls short.

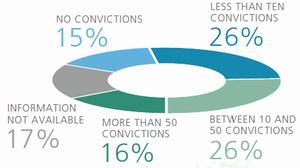

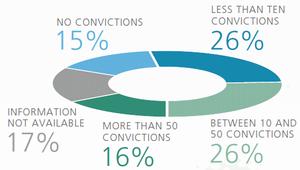

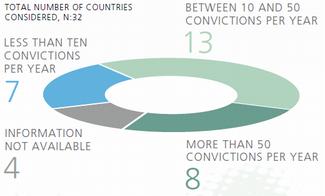

As a result, the number of convictions globally has remained extremely low. Between 2010 and 2012, some 40 per cent of countries reported less than 10 convictions per year. Some 15 per cent of the 128 countries covered in this report did not record a single conviction. The previous Global Report similarly found that 16 per cent of countries recorded no convictions between 2007 and 2010.

At the same time, we have continued to see an increase in the number of detected child victims, particularly girls under 18.

Most detected trafficking victims are subjected to sexual exploitation, but we are seeing increased numbers trafficked for forced labour.

Between 2010 and 2012, victims holding citizenship from 152 different countries were found in 124 countries. It should be kept in mind that official data reported to UNODC by national authorities represent only what has been detected. It is clear that the reported numbers are only the tip of the iceberg.

It is equally clear that without robust criminal justice responses, human trafficking will remain a low-risk, high-profit activity for criminals.

Trafficking happens everywhere, but as this report shows most victims are trafficked close to home, within the region or even in their country of origin, and their exploiters are often fellow citizens. In some areas, trafficking for armed combat or petty crime, for example, are significant problems.

Responses therefore need to be tailored to national and regional specifics if they are to be effective, and if they are to address the particular needs of victims, who may be child soldiers or forced beggars, or who may have been enslaved in brothels or sweatshops.

Governments need to send a clear signal that human trafficking will not be tolerated, through Protocol-compliant legislation, proper enforcement, suitable sanctions for convicted traffickers and protection of victims.

I hope the 2014 report, by providing an overview of patterns and flows of human trafficking at the global, regional and national levels, will further augment UNODC's work to support countries to respond more effectively to this crime.

We have seen that governments and people everywhere are approaching human trafficking with greater urgency. This year, we marked the first ever United Nations World Day against Trafficking in Persons on 30 July, which provided a much-needed opportunity to further raise awareness of modern slavery.

But we need to advance from understanding to undertaking, from awareness to action. The gravity of this continuing exploitation compels us to step our response.

Yury Fedotov

Executive Director

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

CORE RESULTS

- Data coverage: 2010-2012 (or more recent).

- Victims of 152 different citizenships have been identified in 124 countries across the world.

- At least 510 trafficking flows have been detected.

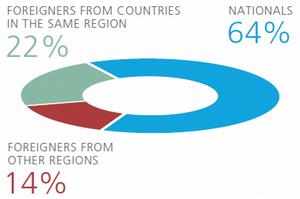

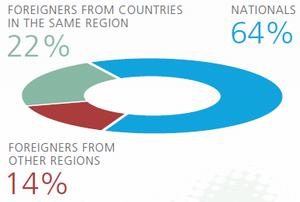

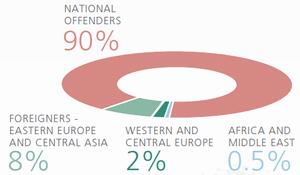

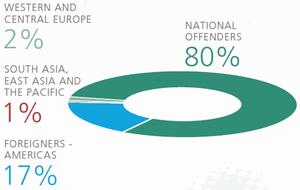

- Some 64 per cent of convicted traffickers are citizens of the convicting country.

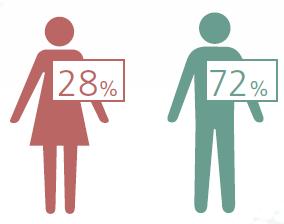

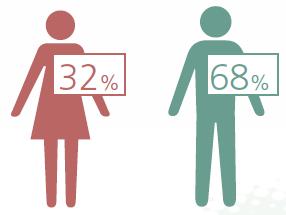

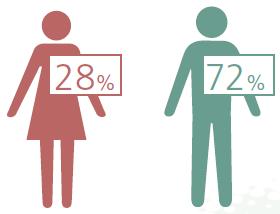

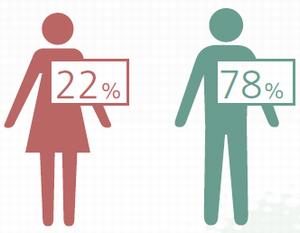

- Some 72 per cent of convicted traffickers are men, and 28 per cent are women.

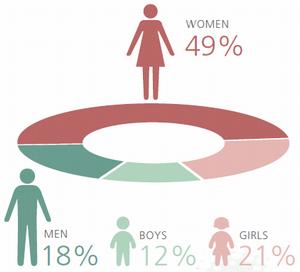

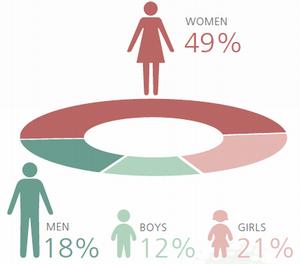

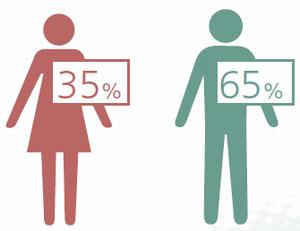

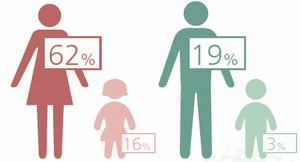

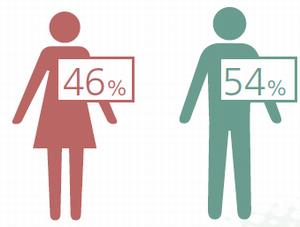

- 49 per cent of detected victims are adult women.

- 33 per cent of detected victims are children, which is a 5 per cent increase compared to the 2007-2010 period.

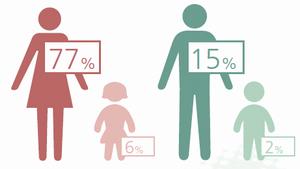

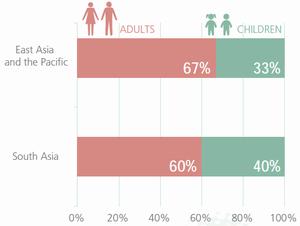

Detected victims of trafficking in persons, by age and gender, 2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

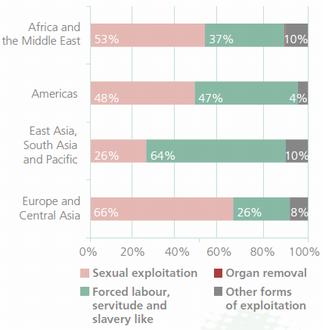

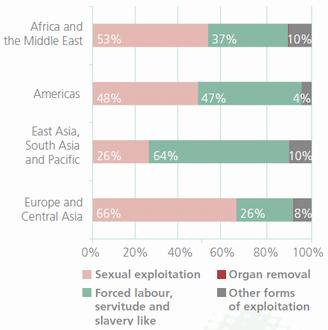

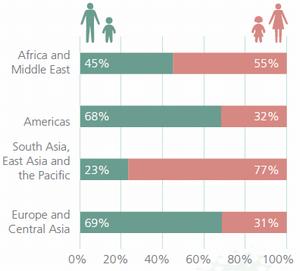

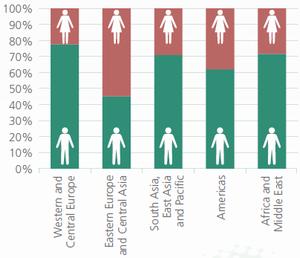

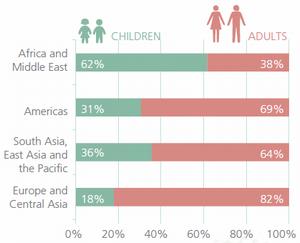

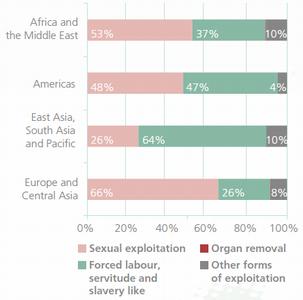

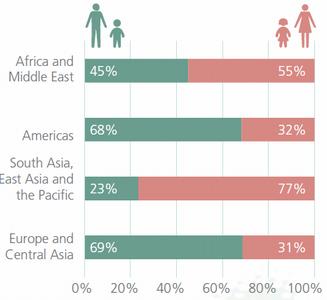

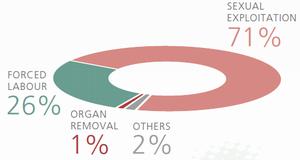

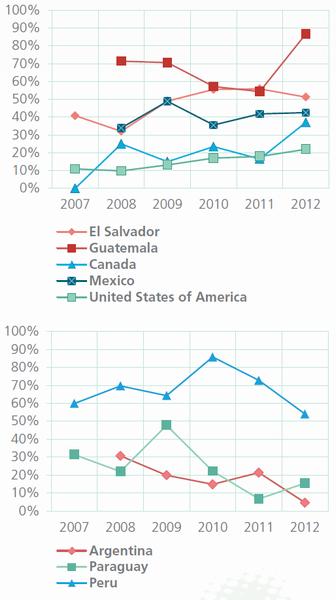

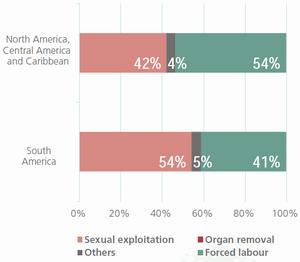

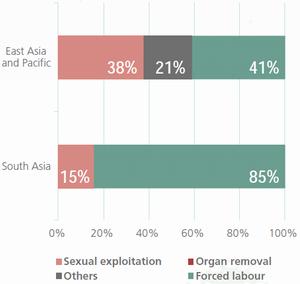

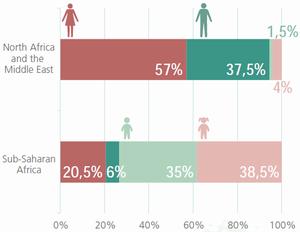

The data collection has revealed wide regional difference with regard to the forms of exploitation (see figure).

Forms of exploitation among detected trafficking victims, by region of detection, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS HAPPENS EVERYWHERE

The crime of trafficking in persons affects virtually every country in every region of the world. Between 2010 and 2012, victims with 152 different citizenships were identified in 124 countries across the globe. Moreover, trafficking flows - imaginary lines that connect the same origin country and destination country of at least five detected victims – criss-cross the world. UNODC has identified at least 510 flows. These are minimum figures as they are based on official data reported by national authorities. These official figures represent only the visible part of the trafficking phenomenon and the actual figures are likely to be far higher.

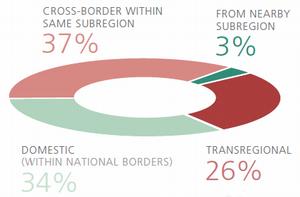

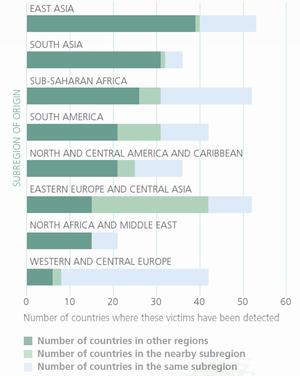

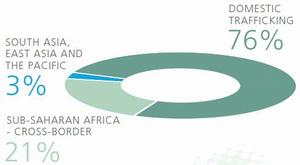

Most trafficking flows are intraregional, meaning that the origin and the destination of the trafficked victim is within the same region; often also within the same subregion. For this reason, it is difficult to identify major global trafficking hubs. Victims tend to be trafficked from poor countries to more affluent ones (relative to the origin country) within the region.

Transregional trafficking flows are mainly detected in the rich countries of the Middle East, Western Europe and North America. These flows often involve victims from the 'global south'; mainly East and South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Statistics show a correlation between the affluence (GDP) of the destination country and the share of victims trafficked there from other regions. Richer countries attract victims from a variety of origins, including from other continents, whereas less affluent countries are mainly affected by domestic or subregional trafficking flows.

Main destination areas of transregional trafficking flows (in blue) and their significant origins, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC.

2. A TRANSNATIONAL CRIME THAT OFTEN INVOLVES DOMESTIC OFFENDERS AND LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL REACH

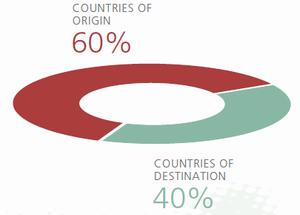

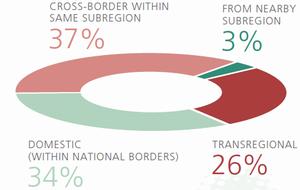

Most victims of trafficking in persons are foreigners in the country where they are identified as victims. In other words, these victims - more than 6 in 10 of all victims -have been trafficked across at least one national border. That said, many trafficking cases involve limited geographic movement as they tend to take place within a subregion (often between neighbouring countries). Domestic trafficking is also widely detected, and for one in three trafficking cases, the exploitation takes place in the victim's country of citizenship.

A majority of the convicted traffickers, however, are citizens of the country of conviction. These traffickers were convicted of involvement in domestic as well as transnational trafficking schemes.

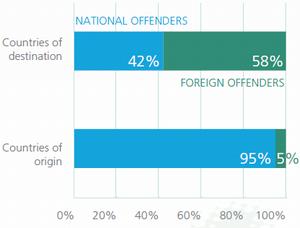

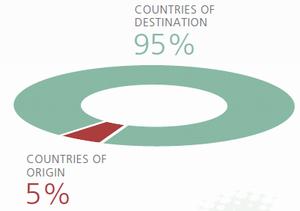

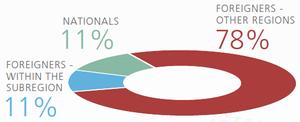

Dividing countries into those that are more typical origin countries and those that are more typical destinations for trafficking in persons reveals that origin countries convict almost only their own citizens. Destination countries, on the other hand, convict both their own citizens and foreigners.

Moreover, there is a correlation between the citizenships of the victims and the traffickers involved in cross-border trafficking. This correlation indicates that the offenders often traffic fellow citizens abroad.

Breakdown of trafficking flows by geographical reach, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

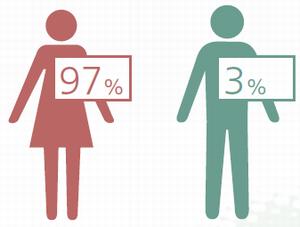

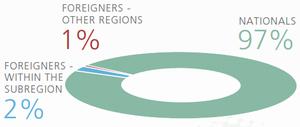

Citizenship of convicted traffickers globally, 2010-2012 (or more recent); shares of local and foreign nationals (relative to the country of conviction)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

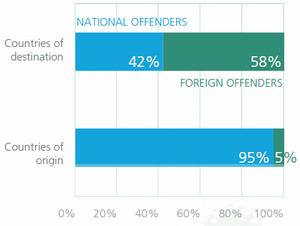

Distribution of national and foreign offenders among countries of origin and destination of cross-border trafficking, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

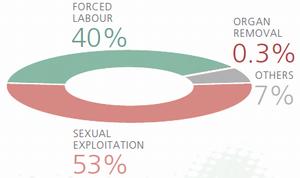

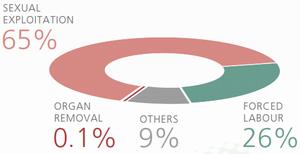

3. INCREASED DETECTION OF TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS FOR PURPOSES OTHER THAN SEXUAL EXPLOITATION

While a majority of trafficking victims are subjected to sexual exploitation, other forms of exploitation are increasingly detected. Trafficking for forced labour - a broad category which includes, for example, manufacturing, cleaning, construction, catering, restaurants, domestic work and textile production – has increased steadily in recent years. Some 40 per cent of the victims detected between 2010 and 2012 were trafficked for forced labour.

Trafficking for exploitation that is neither sexual nor forced labour is also increasing. Some of these forms, such as trafficking of children for armed combat, or for petty crime or forced begging, can be significant problems in some locations, although they are still relatively limited from a global point of view.

There are considerable regional differences with regard to forms of exploitation. While trafficking for sexual exploitation is the main form detected in Europe and Central Asia, in East Asia and the Pacific, it is forced labour. In the Americas the two types are detected in near equal proportions.

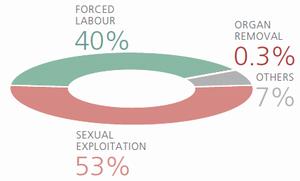

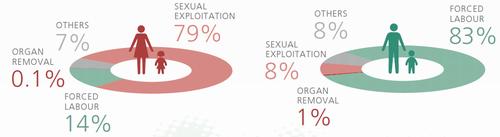

Forms of exploitation among detected trafficking victims, 2011*

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

*Please note that the regional differences in detection capacities and definitions - particularly for forced labour - affect the global shares.

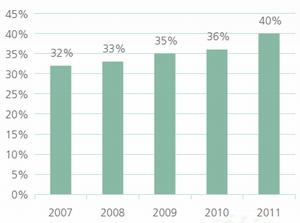

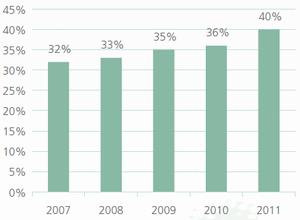

Share of the total number of detected victims who were trafficked for forced labour, 2007-2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

Forms of exploitation among detected trafficking victims, by region of detection, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

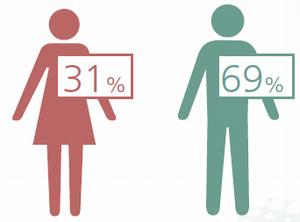

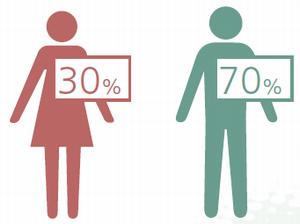

4. WOMEN ARE SIGNIFICANTLY INVOLVED IN TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS, BOTH AS VICTIMS AND AS OFFENDERS

For nearly all crimes, male offenders vastly outnumber females. On average, some 10-15 per cent of convicted offenders are women. For trafficking in persons, however, even though males still comprise the vast majority, the share of women offenders is nearly 30 per cent.

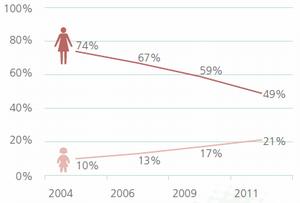

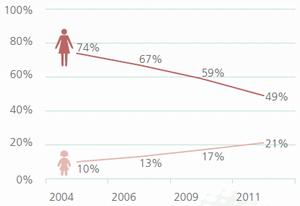

Moreover, approximately half of all detected trafficking victims are adult women. Although this share has been declining significantly in recent years, it has been partially offset by the increasing detection of victims who are girls.

Women comprise the vast majority of the detected victims who were trafficked for sexual exploitation. Looking at victims trafficked for forced labour, while men comprise a significant majority, women make up nearly one third of detected victims. In some regions, particularly in Asia, most of the victims of trafficking for forced labour were women.

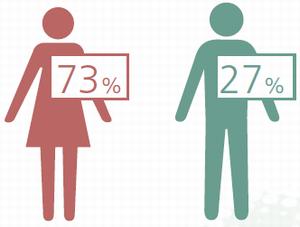

Gender breakdown of detected victims of trafficking for forced labour, by region, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

Persons convicted for trafficking in persons, by gender, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

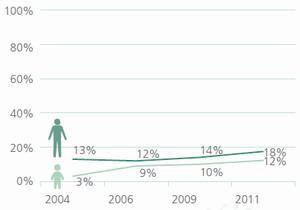

Trends in the shares of females (women and girls) among the total number of detected victims, 2004-2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

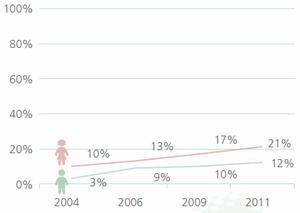

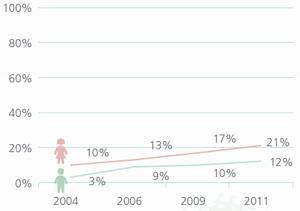

5. DETECTED CHILD TRAFFICKING IS INCREASING

Since UNODC started to collect information on the age profile of detected trafficking victims, the share of children among the detected victims has been increasing. Globally, children now comprise nearly one third of all detected trafficking victims. Out of every three child victims, two are girls and one is a boy.

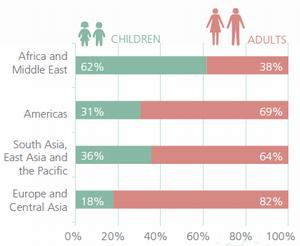

The global figure obscures significant regional differences. In some areas, child trafficking is the major trafficking-related concern. In Africa and the Middle East, for example, children comprise a majority of the detected victims. In Europe and Central Asia, however, children are vastly outnumbered by adults (mainly women).

Trends in the shares of children (girls and boys) among the total number of detected victims, 2004-2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

Shares of children and adults among the detected victims of trafficking in persons, by region, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

6. MORE THAN 2 BILLION PEOPLE ARE NOT PROTECTED AS REQUIRED BY THE UNITED NATIONS TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS PROTOCOL

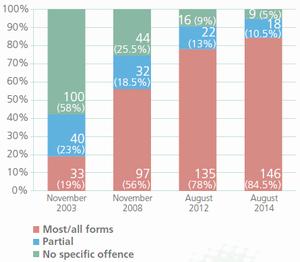

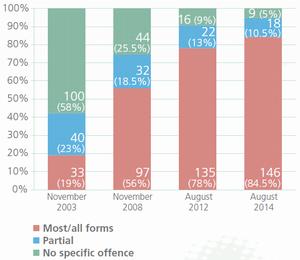

More than 90 per cent of countries among those covered by UNODC criminalize trafficking in persons. Many countries have passed new or updated legislation since the entry into force of the United Nations Protocol against Trafficking in Persons in 2003.

Although this legislative progress is remarkable, much work remains. 9 countries still lack legislation altogether, whereas 18 others have partial legislation that covers only some victims or certain forms of exploitation. Some of these countries are large and densely populated, which means that more than 2 billion people lack the full protection of the Trafficking in Persons Protocol.

Criminalization of trafficking in persons with a specific offence, shares and numbers of countries, 2003-2014

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

Criminalization of trafficking in persons with a specific offence, numbers of countries, by subregion, 2014

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

7. IMPUNITY PREVAILS

In spite of the legislative progress mentioned above, there are still very few convictions for trafficking in persons. Only 4 in 10 countries reported having 10 or more yearly convictions, with nearly 15 per cent having no convictions at all.

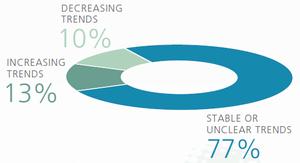

The global picture of the criminal justice response has remained largely stable in recent years. Fewer countries are reporting increases in the numbers of convictions which remain very low. This may reflect the difficulties of the criminal justice systems to appropriately respond to trafficking in persons.

Trends in the number of recorded convictions, share of countries

Sources: UN.GIFT/UNODC, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2009 (2003-2007); UNODC, elaboration on national data (2007-2010 and 2010-2012).

Number of convictions recorded per year, share of countries, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

8. ORGANIZED CRIME INVOLVEMENT: TOWARDS A TYPOLOGY

Criminals committing trafficking in persons offences can act alone, with a partner or in different types of groups and networks. Human trafficking can be easily conducted by single individuals with a limited organization in place. This is particularly true if the crime involves only a few victims who are exploited locally. But trafficking operations can also be complex and involve many offenders, which is often the case for transregional trafficking flows.

Offenders may traffic their victims across regions to more affluent countries in order to increase their profits. However, doing so increases their costs as well as the risks of law enforcement detection. It also requires more organization, particularly when there are several victims. Cross-border trafficking flows – subregional and transregional – are more often connected to organized crime. Complex trafficking flows can be more easily sustained by large and well-organized criminal groups.

The transnational nature of the flows, the victimization of more persons at the same time, and the endurance in conducting the criminal activity are all indicators of the level of organization of the trafficking network behind the flow. On this basis, a typology including three different trafficking types is emerging. The trafficking types have some typical characteristics; however, as always, typologies are based on categorization to better explain and understand different aspects of trafficking. 'Pure' trafficking types may not exist since there is always some overlap between different types.

Typology on the organization of trafficking in persons

SMALL LOCAL OPERATIONS MEDIUM SUBREGIONAL OPERATIONS LARGE TRANSREGIONAL OPERATIONS Domestic or short-distance trafficking flows. Trafficking flows within the subregion or neighboring subregions. Long distance trafficking flows involving different regions. One or few traffickers. Small group of traffickers. Traffickers involved in organized crime. Small number of victims. More than one victim. Large number of victims. Intimate partner exploitation. Some investments and some profits depending on the number of victims. High investments and high profits. Limited investment and profits. Border crossings with or without travel documents. Border crossings always require travel documents. No travel documents needed for border crossings. Some organization needed depending on the border crossings and number of victims. Sophisticated organization needed to move large number of victims long distance. No or very limited organization required. Endurance of the operation.

INTRODUCTION

TRAFFICKERS, ORGANIZED CRIME AND THE BUSINESS OF EXPLOITATION

The crime of trafficking in persons is carried out by different types of traffickers, ranging from individuals exploiting their partner to organized criminal groups operating across national borders. Trafficking in persons is usually thought of as a 'transnational organized crime.' |1| And indeed, many trafficking outfits meet the criteria of transnational organized crime groups, as spelled out in the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. |2| Aspects of the crime are often committed in different countries by criminals not necessarily hailing from the country where the crime was detected. These criminals may have organized themselves to a lesser or greater extent. In some cases the complexity of the crime requires a relatively high level of organization. In other cases, victims of trafficking in persons may have been trafficked by an individual trafficker operating in a local community.

In both cases, the profits that human trafficking can generate is the prime motivation for the criminals, and exploiting other people can be lucrative. Just as profit potential is an important consideration for most legitimate businesses, so it is for traffickers, who have a strong financial incentive to operate where profits are high. Broadly speaking, this means that traffickers will often choose to carry out the exploitation in a location where this will be more profitable. At the same time, traffickers also have to take into account costs and the risk of detection, which tends to increase as more territory and international borders are traversed.

This edition of the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons sheds light on the role of organized crime in trafficking operations, and presents a first step towards a typology of trafficking cases based on the level of organization of the crime as well as of the economic interests behind it. This work is in its infancy and will be further refined as more relevant information becomes available. |3| However, it can already shed some light on the more typical features of many trafficking cases, which will be helpful for designing appropriate responses to this crime.

What is trafficking in persons?

Trafficking in persons can be conceptualized in different ways. This Report employs the definition contained in the United Nations Trafficking in Persons Protocol. |4| According to this definition, which has been adopted by the 160 UN Member States that have ratified the Protocol, |5| there are three distinct 'constituent elements' of trafficking in persons: the act, the means and the purpose. All three elements must be present in order for a case to be defined as a trafficking in persons offence. Each element has a range of manifestations, however.

The Trafficking in Persons Protocol specifies that "the act" means the recruitment, transport, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons. "The means" refers to the method used to lure the victim. Possible means are the threat or use of force, deception, coercion, abduction, fraud, abuse of power or a position of vulnerability, or giving payments or benefits. These terms are not necessarily precise from a legal point of view and may be defined differently by different jurisdictions. "The purpose" is always exploitation of the victim, though this can take on various forms, including sexual exploitation, forced labour, removal of organs or a range of other forms.

The Protocol definition is broad enough to give States Parties considerable leeway in tailoring and adapting their national legislation. This means that adjudicated trafficking crimes can look very different from one country to the next. Couple this with the fact that trafficking in persons affects nearly every country in the world, and the complexity of the trafficking crime is evident.

The Global Report on Trafficking in Persons

In July 2010, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons. |6| The Global Plan was an expression of strong political will among Member States to tackle this heinous crime. Among its provisions was a request for an expanded knowledge base on trafficking in persons. As a result, UNODC was given the mandate and duty to collect data and report biennially on trafficking in persons patterns and flows at the national, regional and international levels.

Research by a global organization like UNODC brings the possibility of obtaining a 'bird's eye view' of the crime of trafficking in persons across the world. From an international perspective, and with data from many Member States in all regions of the world, it is possible to discern whether certain trafficking patterns or forms of exploitation are more prevalent in some areas, and whether certain trafficking flows are becoming more or less pronounced. Such knowledge also has the potential to enhance national-level responses as well as international cooperation in this area. Moreover, in this edition of the Global Report, it is also now possible to present some trend information which will further enhance the relevance and usefulness of the Report.

At present, there is no sound estimate of the number of victims of trafficking in persons worldwide. Due to methodological difficulties and the challenges associated with estimating sizes of hidden populations such as trafficking victims, this is a task that has so far not been satisfactorily accomplished. UNODC has consulted with leading researchers on hidden populations in order to generate recommendations for future research work to produce a global victim estimate; for more information, please refer to the text box 'Towards a global victim estimate?'.

METHODOLOGY

QUANTITATIVE DATA COLLECTION

The data collection for the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons has a dual objective: To achieve the broadest possible geographical coverage by using the most solid information available. While the geographical coverage is crucial for a report that is global in scope, the solidity of information is equally important as UNODC's intention is to produce a report that is reliable and accurate.

The statistical information was collected by UNODC in two ways: through a short, dedicated questionnaire |7| distributed to Governments and by the collection of official information available in the public domain (national police reports, Ministry of Justice reports, national trafficking in persons reports, et cetera). All the information that was collected, regardless of source or method, was shared with national authorities for verification prior to publication of this report.

Some countries were not covered by the data collection. These countries did not respond to the questionnaire, and in addition, UNODC research efforts to locate official national data on trafficking in persons did not yield any results.

Official statistics from national authorities account for 92 per cent of the information collected for this edition of the Global Report. Intergovernmental organizations supplied 5 per cent, and non-governmental organizations the remaining 3 per cent of the data.

DATA COVERAGE

The time period covered by the data is generally 2010-2012. Nearly 20 countries also provided information for the year 2013, and this is normally included in the analysis. Some trend presentations employ data collected for previous UNODC reports on trafficking in persons; in these cases, the sources are specified.

Data on offenders SUSPECTED PERSONS PROSECUTED PERSONS CONVICTED PERSONS Total number of reported offenders 33,860 34,256 13,310 Gender reported 29,568 10,024 4,915 Citizenship reported 5,747 Data on victims Total number of reported victims 40,177 Age reported 34,888 Gender reported 33,111 Age and gender reported 31,766 Citizenship reported 27,052 Countries of repatriation reported (for national victims trafficked abroad) 4,441 Form of exploitation reported 30,592 Gender reported according to form of exploitation 22,405 Reporting from Member States is not uniform. While the questionnaire provides a standard set of indicators, many countries report only partially. For example, some countries may provide citizenships for both offenders and victims, others for victims only, and yet others may only report the gender or age profile of the victims. As a result, the amounts of data that form the basis for the different analyses vary. Below is a breakdown of the data that countries reported to UNODC for each indicator.

These figures represent officially detected offenders and victims. These are persons who have been in contact with an institution – the police, border control, immigration authorities, social services, shelters run by the state or by NGOs, international organizations, et cetera - as a result of their involvement (or potential involvement in the case of suspect offenders, and persons in countries that report data on possible or probable victims of trafficking) in trafficking in persons situations. As for any crime, there is a large and unknown 'dark figure' of criminal activity that is never officially detected. As such, the figures reported here do not reflect the real extent of trafficking in persons, but rather a sample of the population of victims and offenders that is used to analyse patterns and flows of trafficking in persons.

In terms of geographical coverage, information has been collected from 128 countries for this edition of the Global Report. Specific country-level coverage is indicated in the table and map at the end of this section. All regions are covered, although the amount and solidity of the data varies between regions and subregions. Broadly speaking, Europe and Central Asia as well as the Americas have solid data coverage that allows for detailed analyses. Asia and the Pacific, and particularly Africa and the Middle East, are covered, but with significant room for improvement in terms of data quality and quantity.

All the information that was collected for and used in this Report is presented in the country profiles |8| which also specify the information sources.

QUALITATIVE DATA - THE 'COURT CASES'

As explained above, the main data source for the Global Report is statistical criminal justice data officially reported to UNODC by Member States. This data forms the basis for most of the analyses presented in the Report. However, in order to go beyond the statistics, for this edition of the Report, UNODC invited Member States to submit five cases of trafficking in persons that had recently been prosecuted in their jurisdiction. |9| Member States used their own discretion when selecting whether to contribute and which cases to include. This means that cases were not necessarily prosecuted under Trafficking in Persons Protocol-aligned legislation.

This call resulted in some 115 case briefs from nearly 30 different countries across six of the eight subregions used in the Report. These briefs will be referred to as the 'court cases' throughout the Report. About half of the cases were submitted by countries in Europe and Central Asia, and more than a quarter by countries in the Americas. Relatively few Asian and African cases were received.

The submitted material was not uniform, and there were often information gaps that made coding, comparison and analysis challenging. Moreover, the case sample is relatively small and not necessarily representative of the global manifestations of trafficking in persons. Therefore, it cannot be used to draw solid conclusions.

Regardless of the limitations, the wealth of information contained in these real-world cases can enrich our understanding of the patterns and flows of this crime. These cases illustrate some of the many ways in which trafficking in persons is planned and executed in diverse locations, and how criminal justice systems across many jurisdictions are tackling it. Information from the court cases will be presented alongside the quantitative data where relevant throughout the Report. When cases are discussed, the name of the submitting country is stated, but the names of other countries involved in the cases have been omitted.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The report consists of two main analytical chapters. Chapter I provides a global overview of the patterns and flows of trafficking in persons. It also includes an extensive analysis of the role of organized crime elements in the trafficking crime, and an overview of the status of country-level legislation and responses to the trafficking crime. Chapter II analyses patterns and flows of trafficking in persons, as well as the responses to the crime, from a regional perspective. Additionally, the country profiles, which present the country-level information that was collected for this Report, are available on the Report website at www.unodc.org/glotip. These information sheets are divided into four main sections: the country's legislation on trafficking in persons; suspects and investigations; victims; and any additional information on the institutional response.

The 128 countries covered have been categorized into four regions: Europe and Central Asia, the Americas, South and East Asia and the Pacific, and Africa and the Middle East. The order of presentation is based on the size of the sample used for the analysis in each region, with Europe and Central Asia having the highest number of victims reported to UNODC during the period considered. The regional groupings are then further divided into two sub-regions when data coverage allows and doing so helps facilitate more extensive analysis. Europe and Central Asia consists of Western and Central Europe, as well as Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The Americas consists of North and Central America and the Caribbean, as well as South America. South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific consists of South Asia as well as East Asia and the Pacific. Africa and the Middle East consists of North Africa and the Middle East, as well as Sub-Saharan Africa.

Countries covered by the data collection for this report

Source: UNODC.

Note: The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

Regional and subregional designations used in this report

Source: UNODC.

Note: The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST 38 states out of the 66 UN Member States in the region

AMERICAS 29 states out of the 35 UN Member States in the region

EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA 43 states out of the 53 UN Member States in the region

SOUTH ASIA, EAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC 18 states out of the 39 UN Member States in the region

North Africa and the Middle East (11 countries) Sub-Saharan Africa (total: 27) North and Central America and the Caribbean (total: 18) South America (total: 11) Western and Central Europe (total: 34) Eastern Europe and Central Asia (total: 9) East Asia and the Pacific (total: 12) South Asia (6 countries) Algeria Botswana Bahamas Argentina Albania Armenia Australia Bangladesh Bahrain Burkina Faso Barbados Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Austria Azerbaijan Brunei Darussalam India Egypt Cameroon Canada Brazil Bosnia and Herzegovina Belarus China Maldives Israel Cabo Verde Costa Rica Chile Bulgaria Kazakhstan Japan Nepal Jordan Central African Republic Cuba Colombia Croatia Republic of Moldova Malaysia Pakistan Lebanon Comoros Dominican Republic Ecuador Cyprus Russian Federation Myanmar Sri Lanka Morocco Democratic Republic of the Congo El Salvador Guyana Czech Republic Tajikistan New Zealand Qatar Gabon Grenada Paraguay Denmark Ukraine Philippines Tunisia Gambia Guatemala Peru Estonia Uzbekistan Republic of Korea United Arab Emirates Guinea-Bissau Haiti Uruguay Finland Samoa Yemen Kenya Honduras Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) France Thailand Lesotho Jamaica Germany Viet Nam Mauritania Mexico Greece Mozambique Nicaragua Hungary Namibia Panama Ireland Nigeria St. Vincent and Grenadines Italy Republic of Congo Trinidad and Tobago Latvia Rwanda United States of America Lithuania Senegal Malta Seychelles Montenegro Sierra Leone Netherlands South Africa Norway Swaziland Poland Togo Portugal Uganda Romania United Republic of Tanzania Serbia Zimbabwe Slovakia Slovenia Spain Sweden Switzerland The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia Turkey United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

CHAPTER I

GLOBAL OVERVIEWIn the United Nations Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons, |10| Member States requested for the present report to focus on the patterns and flows of trafficking in persons. 'Patterns' refer to the profiles of traffickers and victims; that is, their citizenship, age and gender as well as the forms of exploitation. 'Flows' refer to the geographic dimension of trafficking, with a 'flow' defined as one origin country and one destination country with at least five detected victims during the 2010-2012 reporting period. |11|

A snapshot of the data shows that most of the offenders are men, while most of the detected victims are female (mainly women, but also a significant number of underage girls). Trafficking is a transnational crime that is often carried out domestically or within a given subregion, and most offenders are convicted in their countries of citizenship. Victims, on the other hand, are often foreigners in the country where their exploitation was detected. Trafficking flows are usually confined to a geographically limited area, either within a country or between neighbouring or relatively close countries.

That said, a greater proportion of women are convicted of trafficking in persons than of nearly any other crime, and the detection of male victims is increasing. Many countries convict a significant number of foreigners of trafficking in persons, and many victims are not trafficked abroad but exploited in their own countries. Although transregional trafficking is less common than the domestic or intraregional types, it still accounts for nearly a quarter of all trafficking flows.

This chapter seeks to untangle some of this complexity. It will first present a global overview of patterns and flows, and then, a discussion on markets and organized crime as they relate to trafficking in persons. The chapter closes with an overview of the legislative and criminal justice responses to this crime across the world.

In order to understand the crime of trafficking in persons, it is crucial to know who the offenders are. Analysing the citizenship and gender of traffickers can help generate a broader understanding of the profiles of traffickers and their networks, as well as on how they operate. As trafficking in persons is a crime that is often transnational, the question of traffickers' citizenship is highly relevant, particularly when it comes to cross-border trafficking as there is often a citizenship link between traffickers and victims. Moreover, the issue of female involvement in trafficking in persons is also pertinent.

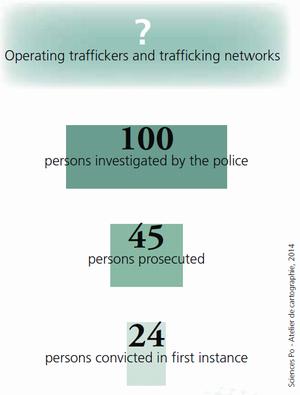

Information on the citizenship of persons convicted |12| of trafficking in persons was provided by 64 countries, covering a total of 5,747 offenders. Information on the gender of suspected, prosecuted and/or convicted offenders was provided by 43, 59 and 64 countries respectively, covering 29,568 persons suspected, 4,915 persons convicted of and 10,024 persons prosecuted for trafficking in persons. The data covers the 2010-2012 period (or more recent).

Citizenship profiles of traffickers

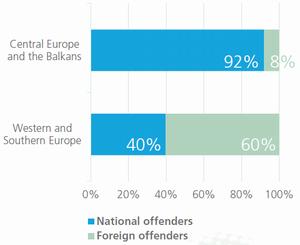

The aggregated citizenship profiles of the people convicted of trafficking in persons show that most offenders are citizens of the country where they were convicted. This is true for more than 6 in 10 convicted traffickers globally. It is reasonable to expect that the majority of people convicted of nearly any crime would be citizens of the prosecuting country. Even though international mobility is high, most people still live and operate mainly within their own countries.

While the majority of offenders are citizens of the country where they were convicted, about 35 per cent of convicted traffickers are foreigners in those countries. This is a larger share of convicted foreigners than what is typically seen for most other crimes, for which foreign citizens generally comprise approximately 10 per cent of those convicted. |13|

FIG. 1: Citizenship of convicted traffickers globally, 2010-2012 (or more recent); shares of local and foreign nationals (relative to the country of conviction)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

The high share of foreign involvement should not be surprising considering the often transnational nature of this crime. As will be presented later in the Report, about two thirds of the human trafficking victims reported to UNODC over the 2010 - 2012 period were exploited in cases that involved at least one border crossing.

When foreign offenders are involved, they tend to come from countries that are relatively close, geographically, to the prosecuting country. Some 22 per cent of those convicted of trafficking in persons are foreigners from countries within the region where they were prosecuted, while 14 per cent are citizens of countries in other regions. This means that in a given country in Asia, for example, it is reasonable to expect that most of the people convicted of trafficking in persons will be citizens of that country. The second largest group will be other Asians, and a relatively small share will be non-Asian foreigners.

This distribution largely follows the breakdown of global trafficking flows, as long-distance (transregional) trafficking is much less frequently detected than domestic or subregional trafficking. However, it should be noted that the share of convicted own citizens among the total number of trafficking offenders is generally much higher than the share of domestic trafficking detected in a given country. This could imply that domestic trafficking -which happens within the borders of one country - is mainly organized by citizens of that country.

MAP 1: Share of foreign offenders among the total number of persons convicted of trafficking in persons, by country, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC.

Note: The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

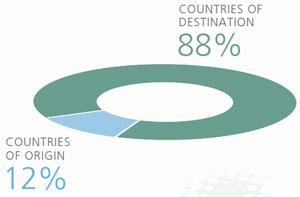

Origin or destination country? In the context of discussing trafficking flows, the question of whether a given country is more of an origin or destination country is very relevant. Understanding whether a country 'sends' or 'receives' more trafficking victims is helpful for discerning transnational trafficking dynamics. It is not possible, however, to make a rigid distinction between origin and destination countries. As with any aggregation, such a broad categorization runs the risk of obscuring important details and highlighting observations that may not be accurate at the micro level. Moreover, domestic trafficking, which is detected in most countries across the world, makes countries origins and destinations simultaneously.

Even if only cross-border trafficking is considered, countries may belong to both categories. Indeed, most countries do, as they detect both outbound trafficking of own citizens and inbound trafficking of foreigners. Only a very few are exclusively origin or destination countries. For this reason, countries may be thought of as being more typical origin or more typical destination countries. While countries play both roles, the majority of the trafficking flows are either outbound (in the case of a more typical origin country) or inbound (more typical destination).

A more typical country of origin of cross-border trafficking may detect some foreign victims who are being exploited within its territory, but the outbound flow of that country's citizens for exploitation in other countries will be far larger.

Out of the 78 countries that provided information concerning the citizenship of the convicted offenders, 37 were considered to be more typical origin countries of cross-border trafficking, whereas 41 were considered more typical destination countries. While it should be kept in mind that the diverse national situations cannot be fully captured by such a broad categorization, when looking at the global level, classifying countries as more typical origin or destination countries of trafficking in persons is nonetheless very useful for trying to understand and describe typical cross-border trafficking flows.

But even so, local citizens are not only engaged in domestic trafficking. Many of those who were convicted in their own countries during 2010 – 2012 were taking part in cross-border trafficking, be it subregional or transregional. Convicted local citizens could be involved in both domestic and cross-border trafficking in some way, for example, as recruiters, transporters, guards or exploiters.

The court cases submitted to UNODC by Member States |14| include an illustrative case from Latvia, where two Latvian men were convicted of trafficking Latvian women to a different country in Western Europe for sexual exploitation. The offenders recruited the victims, deceived them regarding the working conditions they could expect in their destination country by promising a reasonable salary and reassuring them that they would not be involved in prostitution, and then transported the victims across the borders to accomplices. Once in the destination country, the victims were exploited in prostitution against very little pay. In this scheme, the offenders received money from their partners to cover their costs. From the available information, it seems that the convicted men were 'subcontracted' to recruit and transport victims for a larger, foreign-based operation. This shows how convicted persons reported as 'local offenders' may actually be involved in cross-border operations.

Though there are some differences, the overall pattern of offender citizenships in the case of cross-border trafficking holds true globally. But if a distinction is made between origin and destination countries for cross-border trafficking, the picture changes dramatically.

While countries that are more typically origin countries for cross-border trafficking convict mainly local citizens (about 95 per cent of all convictions), more typical destination countries convict fewer own citizens than foreigners of trafficking in persons (58 per cent foreigners, 42 per cent locals). Foreign participation is therefore a key characteristic of cross-border trafficking in persons in destination countries, but not in origin countries.

FIG. 2: Distribution of national and foreign offenders among countries of origin and destination of cross-border trafficking, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

FIG. 3: Convictions of foreign citizens (relative to the convicting country) by countries of origin and destination of cross-border trafficking, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

FIG. 4: Convictions of local citizens (relative to the convicting country) by countries of origin and destination of cross-border trafficking, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

A qualitative analysis of the cross-border trafficking cases within the set of court cases shows that, while victims are normally recruited by local citizens in the victims' own country (origin country), the traffickers who carry out the exploitation in the destination country may be either local citizens of these destination countries or foreigners. Moreover, as shown in the chart above, 58 per cent of traffickers in destination countries are not citizens of the country where they were convicted. Only 5 per cent of all the traffickers convicted in origin countries are foreigners in these countries. While there is insufficient evidence to draw authoritative conclusions, on the base of the official data collected, it can be hypothesized that traffickers in destination countries are often able to recruit or maneuver local traffickers in origin countries.

A closer look at only the foreign citizens convicted of trafficking in persons shows that 95 per cent are convicted in destination countries. For local offenders, on the other hand, the distribution between origin countries and destinations is relatively equal. In other words, national offenders convicted of trafficking in persons may be found in origin and destination countries in similar proportions.

These findings seem to indicate that while recruitments in origin countries are largely carried out by citizens of those countries, the exploitation schemes in destination countries are likely to involve more transnational operators.

Many foreign traffickers also seem to frequently traffic victims from their own country of citizenship. This is confirmed by a clear statistical correlation between the citizenships of victims and offenders in selected destinations of cross-border trafficking. Moreover, in the court cases, many of the case briefs indicated that the citizenships of both trafficker(s) and victim(s) matched. This was particularly apparent when the offender was prosecuted in the destination country for the act of recruitment (sometimes also other acts). This indicates that ethno-linguistic affinities and specific local knowledge may be very useful for traffickers in recruiting their victims.

Gender profiles of traffickers

An analysis of potential offenders' first contact with the criminal justice system – the time of suspicion and/or investigation but before prosecution – shows that 38 per cent of suspected offenders were women during 20102012. This is another anomaly in comparison to other types of crime. While the majority, some 62 per cent, of suspected traffickers are male, the female share is large. These shares are similar, though somewhat smaller, at other stages of the criminal justice process as well: 32 per cent of prosecuted and 28 per cent of convicted traffickers are women. For most other crimes, the share of females among the total number of convicted persons is in the range of 10-15 per cent. |15| Relatively high female involvement appears to be another characteristic of the crime of trafficking in persons.

FIG. 5: Suspected trafficking offenders coming into first contact with the criminal justice system, by gender, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

When looking at the gender and age of offenders and victims, for the period 2007-2010, countries with high rates of female offending were generally countries where many underage female (girl) victims were detected. This could indicate that female traffickers are more frequently involved in the trafficking of girls. |16|

One possible explanation for the high female involvement in this crime is that women might play different roles in the trafficking process; roles that may be more visible and therefore more easily detected by law enforcement. Perhaps women are more frequently used as recruiters, particularly in cases of trafficking for sexual exploitation, as they may be more easily trusted by other females. Women may also be more likely to be assigned roles as guards, money collectors and/or receptionists in places where exploitation takes place. These 'low-ranking' activities are often more exposed to the risks of detection and prosecution. |17| In addition, the roles of women in the human trafficking process often seem to be those that require frequent interaction with victims. This can increase the risk of detection for female offenders since many investigations of trafficking in persons cases rely heavily on victims' testimonies.

FIG. 6: Persons prosecuted for trafficking in persons, by gender, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

FIG. 7: Persons convicted of trafficking in persons, by gender, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

Another factor may be that a relatively high proportion of trafficking cases seems to involve intimate partner and/ or family relations. This was seen in the court cases, where convictions of intimate partners or two or more people in close family relationships were reported from several countries.

Intimate and/or close family relationships and trafficking in persons offending One of the characteristics of the crime of trafficking in persons is the large extent of female involvement. Not only do women and girls comprise the vast majority of detected victims worldwide, but women are also prosecuted and convicted of the trafficking crime far more often than for most other types of crime. Some 30 per cent of convicted traffickers worldwide between 2010 and 2012 were women, whereas the average female conviction rate for other crimes is usually in the region of 10-15 per cent.

Offending linked to intimate relationships, as well as close family relationships (parent-child or siblings), may be a factor in explaining why female offending is higher for trafficking in persons than for other crimes. In the court cases submitted to UNODC by Member States (some 115 cases submitted by nearly 30 different countries), there were many cases that saw convictions of couples, and some that involved mother-daughter pairs or siblings. While there were more men than women among the total number of convicted traffickers, the proportion of women offenders who were convicted alongside an intimate partner or close family member was larger than for men.

Several of the court cases that involved couples were transnational and involved trafficking of women for sexual exploitation. In these cases, the couples often lived in a destination country, and either one or both of the spouses were citizens of an origin country. Victims were usually recruited from the origin country, by the person with background from that country, and then transported for exploitation in the couple's adopted country. The offenders generally collaborated in the exploitation; the person who carried out the recruitment did not limit his/her participation to that phase of the crime. Such cases were reported from several destination countries.

For example, in one court case reported by Denmark, a couple with background from an East Asian country was convicted of trafficking four women from their origin country for sexual exploitation in Denmark. The female partner travelled to her origin country to carry out the recruitment; a task made easier by her prior experience working in the sex industry in her new country. The case notes confirm that the partners took equal part in the offence, and they received the same sentence, which included a permanent entry ban from their adopted country.

Similar cases have been registered in many countries around the world. These cases could be either domestic or transnational. One of the transnational court cases, submitted by Belarus, saw the conviction of a couple for trafficking six women from that country into sexual exploitation in a country in Western and Central Europe. Both perpetrators received 5-year prison sentences. One of the offenders was a citizen of Belarus, and the other, of the country where the exploitation took place. There were also other accomplices who were charged in separate cases. The victims were recruited through deception and subsequently 'sold' to owners of nightclubs in the receiving country.

While there were more cases of sexual exploitation in the court cases, couples and close family members also carry out trafficking for forced labour, as in a case from Mexico that saw the conviction of two women who were related. Together, they trafficked eight children from their native country to a neighbouring country for exploitation in forced labour. The children were made to clean car windshields and sell flowers, with the traffickers taking away the profits of their work. Moreover, an Israeli case saw an elderly couple convicted of trafficking for forced labour. They exploited their foreign housekeeper by making her work excessive hours, controlling her movements and not permitting breaks or holidays. The two perpetrators both received 4-month prison sentences. Although women offenders seem to be more frequently involved in trafficking for sexual exploitation, they also partake in trafficking for forced labour. The cases suggest that female offending is often linked to close personal relationships.

FIG. 8: Persons convicted of trafficking in persons, by gender and (sub)region, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

There are some regional differences in terms of the gender breakdown of persons prosecuted for and convicted of trafficking in persons. Female offending rates in Eastern Europe and Central Asia are higher than the global average. Africa and the Middle East, as well as the subregion of Western and Central Europe, report relatively low shares of convicted female offenders.

An analysis of the profiles of detected trafficking victims over the 2010-2012 period confirms the broad pattern reported previously by UNODC |18| covering the 2003-2010 period. The vast majority of the victims detected globally are females; either adult women or underage girls. The overall profile of trafficking victims may be slowly changing, however, as relatively fewer women, but more girls, men and boys are detected globally.

Information on the age and gender of trafficking victims was provided by 80 countries. It covers a total of 31,766 victims detected between 2010 and 2012 whose age and gender were reported.

FIG. 9: Detected victims of trafficking in persons, by age and gender, 2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

Adult women continue to comprise the largest group of detected victims, as approximately half of the total number are women. Although this is a large proportion, it has decreased markedly, which is in line with the trend reported in previous editions of this Report. This reduction in the number of women is partially offset by the increasing detection of girls, who now comprise around one fifth of the total number of detected victims worldwide. As a result, while the proportion of detected female victims is clearly decreasing, it is not decreasing as steeply as the trend for adult women.

During the 2010-2012 period, the share of males among the total number of victims detected globally ranged between 25 and 30 per cent. This is an increase compared to the years 2006 and 2009. The trend of underage boy victims has increased since 2004. While increases can be seen for both men and boys, it is more pronounced for men. The key reason seems to be the greater number of detected cases of trafficking for forced labour in many countries, as this type of trafficking involves more male than female victims.

The previously reported trend of an overall lowering of the average age of detected victims has been confirmed by the data collected for this Report. Child trafficking, in which victims are below 18 years of age, accounts for more than 30 per cent of the total number of victims detected during the 2010-2012 period. The proportion of detected child victims has increased significantly in recent years.

Towards a global victim estimate? The question of the magnitude of the trafficking problem – that is, how many victims there are – is hotly debated as there is no methodologically sound available estimate. In December 2013, UNODC hosted a meeting with academics and researchers with experience in uncovering various 'hidden populations'. The objective of the meeting was to obtain an overview of successful methodologies in enumerating hidden populationsI and to discuss research methods on trafficking in persons, with particular emphasis on the potential development of a global victim estimate.

The experts encouraged UNODC to avoid generic global or regional extrapolations based on weak methodologies. The data currently available to UNODC and the complexity of the phenomenon do not support the development of a reliable global victim estimate based upon a sound methodology. In order to start filling the data gaps, which are particularly acute in developing countries, the experts concluded that:

1. UNODC could initiate a series of small field studies to be conducted at local levels in different parts of the world. Such studies may only be considered as representative of the specific geographical realities and for the specific forms of trafficking considered.

2. Such studies should be based on a multiple steps approach:

- Conduct preliminary assessment and literature review of the forms of trafficking in persons and exploitation (sexual, labour, begging, domestic servitude, et cetera) occurring in the region concerned, and thus focus the field work on the most relevant.

- Define strict geographical boundaries.

- Carefully define tight indicators for trafficking in persons that are appropriate for the local realities and the forms of trafficking under consideration.

- Design modular questionnaires for different sub-populations.

- Identify the best sampling designs for the population considered and endeavour to use multiple validating approaches (respondent-driven sampling, geo-mapping, network scale-up, capture-recapture).

- Participate in the field studies.

Once a critical mass of small studies has been completed, a more comprehensive assessment of the severity of trafficking in persons may be carried out.

Additionally the experts encouraged UNODC to try to take advantage of existing data collection vehicles by making efforts to have relevant trafficking in persons-related questions included. This is particularly relevant for industrialized countries as these often carry out various national surveys with some regularity. There are also some United Nations-led surveys that could be used similarly.

Generating a methodologically sound estimate of the global number of trafficking victims is a commendable objective. Achieving it, however, would require significant resources and a long-term perspective.

I Further information on the research methodologies and approaches discussed at the expert meeting can be found in the next edition of the UNODC journal Forum on Crime and Society (forthcoming 2015). The meeting participants were: Kelle Barrick (RTI – Research Triangle Institute, United States), Jan van Dijk (Tilburg University, the Netherlands), Peter van der Heijden (Utrecht University, the Netherlands/ University of Southampton, United Kingdom), John Picarelli (United States Department of Justice), Michael 'Trey' Spiller (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States), Thomas M. Steinfatt (University of Miami, United States), Ieke de Vries (National Rapporteur on Trafficking in Human Beings and Sexual Violence against Children, the Netherlands) and Sheldon X. Zhang (San Diego State University, United States).

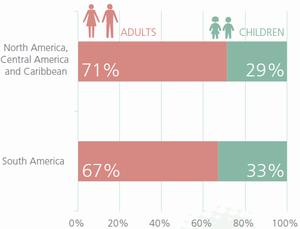

However, increasing shares of children among the detected victims were not witnessed across all regions or areas. While Africa and the Middle East, North and Central America, as well as some countries in South America did register clear increases during the 2010-2012 period, in other regions of the world, such as Europe and Central Asia as well as South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific, child trafficking remained relatively stable compared to the 2007-2010 period.

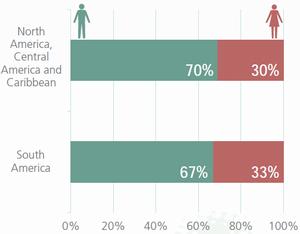

The patterns of trafficking in persons continue to show pronounced regional differences. Children comprise the majority of victims detected in Africa and the Middle East, accounting for more than 60 per cent of the victims in this region. In Europe and Central Asia, trafficking in persons mainly concerns adult victims, as they comprise 83 per cent of the victims detected there. South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific and the Americas report similar age profile breakdowns, with adults comprising about two thirds of the detected victims, with children making up the remaining one third.

FIG. 10: Trends in the shares of females (women and girls) among the total number of detected victims, 2004-2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

FIG. 11: Trends in the shares of males (men and boys) among the total number of detected victims, 2004-2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

FIG. 12: Trends in the shares of children (girls and boys) among the total number of detected victims, 2004-2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

FIG. 13: Shares of children and adults among the detected victims of trafficking in persons, by region, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

Recruitment through feigned romantic relationships The recruitment of victims is an essential part of the trafficking process. Though the recruitment can happen in many ways, it often involves deception. The victim may be deceived about work conditions such as the type of job, the workplace and the salary. In other cases, criminals deceive by feigning a romantic interest and entering into a relationship with the victim in order to gain her trust. Victims of this type of recruitment are often underage, but may also be adults. Generally, the perpetrator is male and the victim female. As the 'relationship' develops, the exploiter manipulates and/or coerces the victim into sexual exploitation, from which he obtains the profits.

This type of recruitment has been denounced by the Dutch authorities for more than a decade.I However, feigned romantic relationships is a relatively common recruitment method in many countries. The court cases submitted to UNODC by Member States included several clear cases of such recruitments, and even more where this method may have been used, but the information is insufficient to establish with certainty. While most of these cases originated from countries in the Americas, there were also cases from other parts of the world.

Many of the court cases involved domestic trafficking situations where one man recruited one victim, often an underage girl. In one case from Mexico, for example, a man met his 16-year-old victim at the video game parlour where she worked. He courted her, they began dating, and eventually moved together to a different city. Once there, he forced her into prostitution and took away the money paid by the customers. He also threatened and beat her. In this case, the offender was acting alone, and he was sentenced to nine years' imprisonment.

In another court case, reported by Canada, 10 males - including one minor boy - were convicted of trafficking four underage girls. The sentences ranged from one to three years of imprisonment. The offenders were part of a 'street gang' who carried out a relatively extensive trafficking operation in which the minor boy was the recruiter. He operated at schools were he could easily make contacts with multiple underage girls. Some of the girls fell in love with him and once trust had been established, the girls were introduced to the other, older gang members. The victims were then forced, under threats of violence, to abide by strict rules and provide sexual services for payments the traffickers then collected. Here, the recruitment through the feigned romantic relationship was one part of a larger scheme to exploit several girls.

This type of recruitment does not necessarily have to occur in a domestic context, however. In a court case from Brazil, a European man was found guilty of recruiting a local woman in Brazil through a feigned romantic relationship for the purpose of bringing her to Europe for sexual exploitation. The offender pretended that he was in love with the victim, gained her trust, arranged the travel and even paid for her passport. But once they arrived in Europe, the victim was locked in, forced to work as a prostitute and generate a set amount of money for the trafficker each day. The trafficker was sentenced to five years' imprisonment.

These cases show that recruitment through feigned romantic relationships can be used either by traffickers operating alone, or as part of a larger group. The exploitation can take place domestically or in another country, and although there were no such cases within the set of court cases, it is not inconceivable that this recruitment method could also be used to deceive potential victims of trafficking for forced labour. Every trafficking case needs at least one victim and feigned romantic relationships is one of the ways criminals go about recruiting victims.

I See, for example, Trafficking in Human Beings, the First Report of the Dutch National Rapporteur, Bureau NRM, The Hague, November 2002.

MAP 2: Share of children among the total number of detected victims, by country, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC.

Note: The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

Exploitation is the source of profits in trafficking in persons cases, and therefore, the key motivation for traffickers to carry out their crime. Traffickers, who may be more or less organized, conduct the trafficking process in order to gain financially from the exploitation of victims. The exploitation may take on a range of forms, but the principle that the more productive effort traffickers can extract from their victims, the larger the financial incentive to carry out the trafficking crime, remains.

Victims may be subjected to various types of exploitation. The two most frequently detected types are sexual exploitation and forced labour. The forced labour category is broad and includes, for example, manufacturing, cleaning, construction, textile production, catering and domestic servitude, to mention some of the forms that have been reported to UNODC. Victims may also be trafficked for the purpose of organ removal, or for various forms of exploitations that are not forced labour, sexual exploitation or organ removal. These forms have been categorized as 'other forms of exploitation' in this Report, and this Section will also examine the detections of these 'other forms' in some detail.

Information on the forms of exploitation was provided by 88 countries. It refers to a total of 30,592 victims of trafficking in persons detected between 2010 and 2012 whose form of exploitation was reported.

Looking first at the broader global picture, some 53 per cent of the victims detected in 2011 were subjected to sexual exploitation, whereas forced labour accounted for about 40 per cent of the total number of victims for whom the form of exploitation was reported.

FIG. 14: Forms of exploitation among detected trafficking victims, 2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

FIG. 15: Share of detected victims trafficked for forced labour, 2007-2011

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

While among the detected trafficking victims, sexual exploitation is the largest category, the share of forced labour detections is increasing. The increasing detections of trafficking for forced labour has been a significant trend in recent years

Trafficking for sexual exploitation is the major detected form of trafficking in persons in Europe and Central Asia. More than 65 per cent of the victims detected in this region are trafficked for sexual exploitation. In the subre-gion of Eastern Europe and Central Asia in particular, sexual exploitation is frequently detected, accounting for 71 per cent of the victims (see also the regional overview).

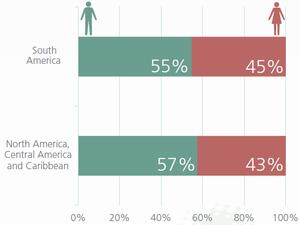

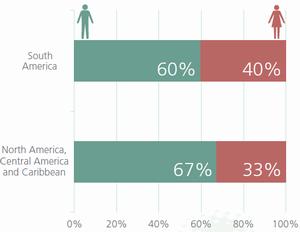

In the other regions, the shares of trafficking for forced labour are far higher than in Europe and Central Asia. In South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific, trafficking for forced labour is the major detected form of trafficking as it accounts for nearly two thirds of the detected victims. In the subregion of South Asia, over 80 per cent of the reported victims are trafficked for forced labour (see the regional overview). In the Americas, trafficking for forced labour and trafficking for sexual exploitation are detected in nearly identical proportions.

There are some differences between the two subregions of the Americas, however. In North America, Central America and the Caribbean, more than 50 per cent of the detected victims are exploited in forced labour, whereas in South America, the percentage is around 40. The proportion of detected trafficking for forced labour in South America is a likely underestimation as this category does not include the large number of victims of 'slavery and slavery-like conditions'. These victims are not officially recorded as trafficking victims as it is unknown to which extent they are in exploitative situations as a result of a trafficking process. If the victims who are exploited under 'slavery or slavery-like conditions' |19| in South America would be considered trafficking victims, the share of victims of trafficking in persons for forced labour globally would be considerably larger.

FIG. 16: Forms of exploitation among detected trafficking victims, by region, 2010-2012 (or more recent)

Source: UNODC elaboration on national data.

Globally, ten types of exploitation different from sexual exploitation, forced labour or organ removal were identified by the national authorities during the reporting period. These types are trafficking for mixed exploitation in forced labour and sexual exploitation, for committing crime, for begging, for pornography (including internet pornography), forced marriages, benefit fraud, baby selling, illegal adoption, |20| armed combat and for rituals.

MAP 3: Countries that report forms of exploitation other than forced labour, sexual exploitation or organ removal, 2010-2012

Source: UNODC.

Note: The boundaries shown on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Dashed lines represent undetermined boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. The final boundary between the Sudan and South Sudan has not yet been determined.

There are pronounced regional differences with regard to these 'other forms of exploitation'. While in Europe and Central Asia, this category mainly includes begging and victims trafficked to commit (often petty) crime, in Sub-Saharan Africa, it often entails trafficking of children for armed combat ('child soldiers'). In Asia, the issue of forced marriage is also frequently reported for victims who are not trafficked for sexual exploitation, forced labour or organ removal.

During the reporting period, cases of trafficking for organ removal were detected and reported by 12 countries. These victims account for about 0.2 per cent of the total number of victims. Most of the detected victims of this form of trafficking are males.

In general, the profiles of the victims of trafficking reflect the types of trafficking that are more commonly detected in different parts of the world. The observed correlation between the profile of the detected victims and the type of exploitation is only partial, however, and an analysis of the profiles commonly associated with the different types of trafficking reveals some significant nuances.

Globally, the vast majority of detected female victims are trafficked for sexual exploitation, whereas most of the detected male victims are trafficked for forced labour.

However, a closer look at the broad category of trafficking for forced labour reveals that this is not a crime that only involves male victims. In fact, about one third of the total number of victims detected globally who were trafficked for forced labour are females, and about two thirds are males. In other words, females are also trafficked for forced labour in significant numbers.